Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Garden Futurist, Sustainable Gardening

The rapidity with which the wild flowers are decreasing is most alarming. If we do not begin to preserve them, the time will soon be here when they will become extinct and live only in history.

Theodore Payne, 1916

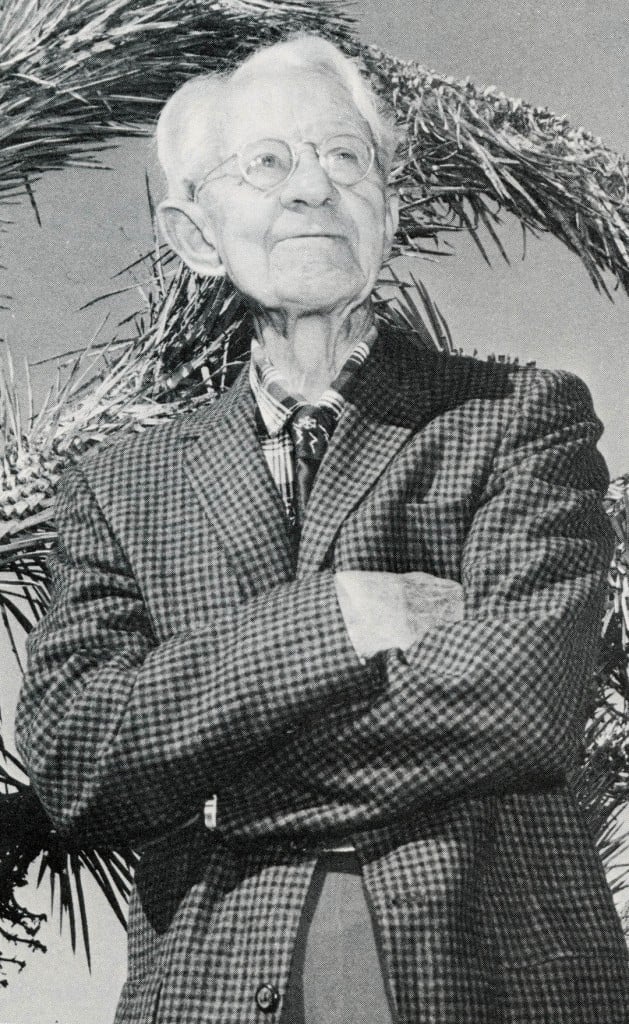

A few days after Christmas 1962, Theodore Payne, then ninety years old, visited fellow plantsman Eddie Merrill, owner of La Tuna Nursery on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Payne had just published a volume of memoirs, Life on the Modjeska Ranch in the Gay Nineties, and he brought a copy as a gift for his friend. Having operated his own nursery for fifty-five years, Payne naturally looked over Merrill’s stock of conifers and California natives and even climbed the hill to collect some zauschneria seeds. As Merrill would note on the endpapers of the gift book, this was Payne’s last visit to La Tuna. The Englishman turned Californian who did so much to encourage the preservation and cultivation of the state’s native plants, died May 6, 1963. Today the twenty-one-acre canyon site once occupied by La Tuna Nursery is home to the Theodore Payne Foundation for Wild Flowers and Native Plants.

Born in England in 1872, young Theodore Payne displayed a love of nature and of gardening encouraged by his mother. At age sixteen he was apprenticed to a nursery firm, receiving five shillings for a week of twelve-hour workdays. His stint completed, he left Northamptonshire for the United States and celebrated his twenty-first birthday at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. He arrived in California in July of that year and, unable at first to find a nursery position, took a job as gardener on the ranch of Polish actress Helena Modjeska.

The Modjeska Ranch, in Santiago Canyon in the Santa Ana Mountains, was a fabulous introduction to California for the young Englishman. He quickly made the acquaintance of rattlesnakes, hummingbirds, a mountain lion, and an Indian woman who laundered his clothes with mashed soap lily (Chlorogalum) bulbs. On afternoon walks he met wild larkspurs, penstemons, mariposa lilies, and other wildflowers to which he would devote his life.

The first winter Payne spent on the ranch was a dry one, with less than seven inches of rain recorded in Los Angeles. The following summer he had his hands full irrigating the garden. He explains:

It was very slow work, drawing the water up a bucket at a time from the well, emptying it into a barrel, then bailing it out again and carrying it to each plant, but it was the only way I could keep things alive… By 2 o’clock the well was empty. The next day I emptied the well before noon and a few days later by 11 o’clock. After about three weeks I could empty this well before breakfast.

While still on the ranch Payne made his first attempt at growing native plants, choosing a worthy but difficult subject for his debut. The seeds of Matilija poppies (Romneya coulteri) he collected and planted refused to sprout, and only later did he learn to burn straw over the seedbed to stimulate germination. It is tempting to speculate that Payne’s interest in cultivating drought-tolerant natives was sparked by the rigorous routine of carrying water to Madame Modjeska’s roses. If such was the case, the drought of 1893–4 was a seminal one for California horticulture.

The Modjeska Ranch was a lively and hospitable place when the owner and her retinue were in residence. However, Payne was lonely much of the time, pruning olive trees for weeks on end, some days seeing more bobcats than people. He decided that he needed to get back to the nursery and seed business for which he had been so thoroughly trained. Returning to Los Angeles, he took a job at Germain’s Seed Company, eventually rising to manager there before buying his own business in 1903. The nursery he purchased, then owned by Hugh Evans, had earlier been the property of pioneer Los Angeles plantsman William S. Lyon, for whom Lyonothamnus and Prunus Iyonii are named.

From the beginning California natives were a specialty of Payne’s nursery, and by 1906 its catalog listed fifty-six native plants. Payne created demonstration plantings on vacant lots in Hollywood and Pasadena and, in 1915, a five-acre native plant garden in Exposition Park.

This was an era of rapidly expanding agriculture, and as soon as Payne would get to know an area it was lost to crops or orchards. “I can distinctly remember when the State was almost covered with wild flowers,” he wrote. “Wherever you looked or stepped there were acres of purple owl’s clover, yellow tidy tips, golden poppies. But often returning to a favorite haunt, I would find that many of them had disappeared completely.”

Soon native plants, both their cultivation and their preservation in the wild, became Payne’s consuming interest and the sole focus of his business. He lectured on preserving the wildflowers and native landscapes of California and he played a key role in the development of two southern California gardens devoted to the native flora, the Rancho Santa Ana and Santa Barbara Botanic Gardens.

The population boom California experienced after World War II further intensified the pressures on native wildflowers, but their champion was growing old. When Payne finally retired in 1958 it appeared that no one would fill the void he left, so his friends and supporters formed the Theodore Payne Foundation, Inc., to carry on his work.

The Foundation and Nursery

The early directors of the Theodore Payne Foundation, which was established with Payne’s blessing in 1960, struggled for years to find a suitable location for a nursery. Moved by their plight, Eddie Merrill donated his land in La Tuna Canyon, where the foundation has operated its nursery, seed business, and bookshop since 1966.

If Payne could visit the nursery that bears his name today, he surely would approve of the great variety of native plants offered to the public, ranging from Limonium californicum of coastal salt marshes to Sedum obtusatum from alpine fell-fields and desert holly (Atriplex hymenelytra), a conspicuous denizen of Death Valley. Along with wild plants, the nursery grows hybrids and named selections of California lilac (Ceanothus), manzanita (Arctostaphylos), and other genera, nearly all of which have been introduced since Payne’s death. The foundation’s emphasis on propagating rare and endangered plants is a direct legacy of its namesake. For decades Payne urged the cultivation of Nevin’s mahonia (Mahonia nevinii), Conejo buckwheat (Eriogonum crocatum), and other rare local endemics.

Annual wildflowers were Payne’s special love, and the hill where he collected seeds on his last visit to La Tuna is now a thriving demonstration garden of wildflower cultivation called Flowerhill. Flowers that flourished in the San Fernando Valley at the turn of the century, such as golden gilia (Linanthus aureus) and thistle sage (Salvia carduacea), have been reintroduced. Each spring forty or more kinds of plants bloom on Flowerhill, and harvested seed is sold for garden and revegetation use.

After a rain or when Santa Ana winds blow the smog away, the top of the hill affords a panoramic view of the Verdugo Mountains, the San Fernando Valley, and the Santa Monica Mountains in the distance. Slopes in the immediate vicinity are covered with coastal sage scrub and remnants of old olive groves, but the floor of the valley was long ago overrun by the expanding metropolis. Neighboring Simi Valley and the canyons and ridges of the Santa Monica and Santa Susana mountains, where Payne collected seeds, now sprout more houses every day, while efforts to purchase land for preservation are stalled. Payne might be startled by the pace and magnitude of habitat loss, but not by the process itself, for he lived long enough to see what was happening to the native flora. He had arrived in California early enough to have known it as “one vast garden of wild flowers.”

California Wildflowers Today

Nearly a century after Theodore Payne collected his first Matilija poppy seeds in Santiago Canyon, we might take stock of the status of the California wildflowers he loved so well. The staggering population growth of the postwar era spelled doom for vast tracts of wildflowers, but even where wildflowers could have been preserved, cheap and plentiful imported water favored summer-irrigated plantings at the expense of native vegetation. Wildflowers have virtually disappeared from the coastal plain and valleys that comprise Los Angeles and its suburbs. A researcher recently sought advice from the foundation on where to find coastal populations of Phacelia douglasii, a dainty and attractive annual that once grew along the coastal strand of Los Angeles County. We could think of no location for the plant closer than forty-five miles from the coast.

Many other plants that were common in coastal southern California now are found in abundance only in the Antelope Valley on the western edge of the Mojave Desert. City dwellers make springtime pilgrimages to see California poppies, cream cups, owl’s dover, and thistle sage, imagining these remnants of the coastal flora to be true desert plants. Soon this refuge on the margin of the desert will fall as the communities of Lancaster, Palmdale, and others grow by leaps and bounds.

Los Angeles County’s most dependable wildflower display, on the Gorman hills above Tejon Pass, recently was threatened by a wind farm development. The project was denied, but the Gorman hills, in private ownership, are far from safe. Rapid population growth in Ventura, Riverside, San Bernardino, and San Diego counties mean that they are not far behind Los Angeles and Orange counties.

If the plight of wildflowers in habitat is grim, their status in cultivation is not much brighter. Though gardeners are increasingly aware of the native flora’s ornamental value and adaptability to drought, the variety of available wildflower seed is limited. Southern California real estate is not only too valuable to preserve as habitat; it is also too valuable to be used for seed production. Long gone are the days of Payne’s ten-acre growing grounds on Los Feliz Boulevard. Today several native plants are grown only abroad and must be imported to California, while many more are unobtainable from any commercial source.

Of the twenty-nine plants Payne described in the front of his catalog as the “most popular and showy species of easy culture,” perhaps fifteen currently are grown commercially on a large scale. These do offer a fair sampling of native flowers, including at least one species of the genera Eschscholzia, Lupinus, Gilia, MentzeIia, Phacelia, Layia, Nemophila, Collinsia, and Clarkia. A few others that seem to fall in and out of the trade are dwarf lupine (Lupinus nanus), spider lupine (L. benthamii), chia (Salvia columbariae), and owl’s clover (Orthocarpus purpurascens). But there are at least 150 native annuals that can and should be grown in southern California, so only a meager ten to fifteen percent are available in the wholesale trade.

On the Theodore Payne Foundation’s La Tuna Canyon property all flat ground is used for growing nursery container stock. Wildflower seed is harvested from the unirrigated plantings on Flowerhill, but there are difficulties inherent in combining what is foremost a demonstration garden with the production of seed for sale. Species of Clarkia seed themselves about on the hill and are difficult to differentiate when seed is ready to collect. Hybridization is also a problem in some genera — Phacelia minor and P. parryi, for example, are busily forming a hybrid population. Despite the problems, seed is harvested from a number of plants, including whispering bells (Emmenanthe penduliflora), thistle sage (Salvia carduacea), and white snapdragon (Antirrhinum coulterianum), adding to the few that are commercially field grown.

Over the past fifteen years some worthy plants occasionally have been available from the Theodore Payne Foundation, Earthside Nature Center, the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, or the East Bay Regional Parks Botanic Garden, including Clarkia cylindrica, C. dudleyana, C. biloba, Phacelia viscida, Eschscholzia lobbii, Collomia grandiflora, Platystemon californicus, and Centaurium venustum. A sadder category consists of plants that have been successfully cultivated in the past but have been unobtainable from any commercial source for years. Clarkia williamsonii and Linanthus montanus fall into this group, as does ground pink (Linanthus dianthiflorus), a favorite plant of Payne’s from which he selected several color forms now lost.

At a time when bite-sized vegetables and exotic culinary herbs are painstakingly grown to flavor California cuisine, who will produce the rare wildflower seed for California gardens? The large-scale grower asks: “Why grow both spider lupine and canyon lupine if the latter is more productive and can be sold at a lower price? And if Clarkia amoena from the north coast is the showiest of clarkias, why grow any of the southern California species?” For small concerns, including the Theodore Payne Foundation, the problem is where and at what cost to produce wildflower seed in a part of the state where agriculture has almost disappeared in the face of soaring land values.

Perhaps an Adopt-a-Species approach would help to make seeds of worthy native plants available, at least in small quantities. Whether as a business sideline or as an act of environmental piety, enterprising individuals should undertake the task of cultivating small plots of evening snow (Linanthus dichotomus), hairy lupine (Lupinus hirsutissimus), or any of dozens of other native plants begging for an understanding grower.

In the words of Theodore Payne, “you will be well repaid for the little care and time it is necessary to bestow upon them.”

Responses