The Native Plant Garden in Summer

Contributor

Summer 2021

The floor of the Sacramento Valley is mostly flat agricultural land veined with a network of creeks, sloughs, levees, and dams all constructed to collect and direct winter rainfall. Along such a slough is our one-acre private native garden begun more than 15 years ago by myself, Patricia, and now enjoyed and managed in a wonderful partnership with Pat.

The four months of summer (June to September) are dry and hot—often with days over 100°F. Most mornings we are lucky to enjoy a cooling delta breeze, allowing us to spend time roaming in the garden or catching up on a bit of needed maintenance. But in the afternoons, we head for the dense cool shade of the redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) to enjoy its unique microclimate.

Plant Adaptations to Heat and Drought

The summer season is a time of rest for many perennial plants—and for Pat and me as well. In general, there is much less plant growth. When leaf stomata close to conserve water loss, photosynthesis is also reduced. The heat and lack of summer rains require the California native plants in our garden to adapt in some way. If our drought-tolerant plants have received typical winter and early spring rains of about 18 inches, then in theory they will survive until the next winter rains. It doesn’t mean the plants look nice, however.

Not all our native plants are equally drought tolerant. For instance, in the summer we must water our redwoods and their understory every week or two, plants native to the coastal areas at least monthly, and our valley grassland and desert areas even less. Although we irrigate, this is not enough to keep everything green and causes many plants to respond with browning leaves.

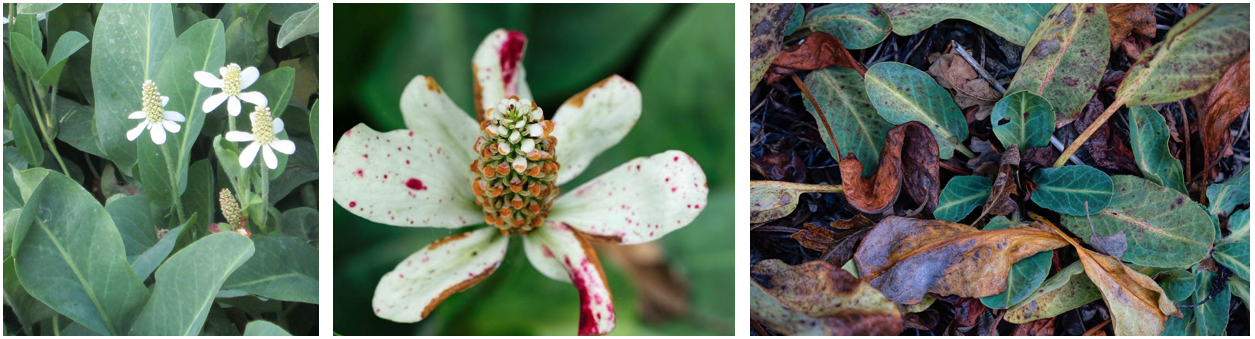

The yerba mansa (Anemopsis californica) is a great example. Each year in early summer the sizeable patch of big green leaves and white flowers causes quite a stir, and everyone just has to have this plant. Sometime in the summer all the leaves start to brown and, sadly, nobody seems to want it. However, we just love how this plant starts to shut down: the white flowers develop red spots and the leaf veins catch the eye with spots and red shapes. The lush green patch changes to a patch with amazing texture. We appreciate and embrace the changing of the season. If yerba mansa is grown in a riparian area that provides more water and shade, it might stay green longer or even all summer.

When we first planted the native garden, the browning and dying leaves of some of the shrubs, ferns, herbaceous perennials, and grasses caused us to panic. Now we expect the wonderful climbing penstemon (Keckielia cordifolia), if stressed, to be leafless in the hot season. Often, new native gardeners don’t understand that when plants seem to be dying it may just be a seasonal response. Numerous deciduous plants just shut down when it is very hot or there is decreasing water, but some will green up when water is again available. It is so very important to know which perennials are winter deciduous and which are drought or summer deciduous! Pat and I are becoming much wiser now.

Unlike summer deciduous plants, evergreen drought-tolerant plants adapt in other, less obvious, ways. Some have thick and leathery leaves that resist dehydration, such as the coffeeberry (Frangula californica), which stands out in the garden when it produces three colors of berries at the same time. Leaf coatings of hair, wax, oil, or microscopic scales also protect a number of plants from water loss and cause the leaves to appear white or gray, which helps to reflect the light. Other plants minimize sun exposure with small leaves or by orienting their leaves more vertically, and a few even change with the angle of the sun. If evergreen plants become extremely stressed, they may also experience browning leaves. Lastly, taproots deep in the soil enable plants to access what little moisture remains as the season progresses.

Succulents

By early summer the succulents are blooming. Their fleshy leaves store needed water, allowing them to survive our summer drought. Many grow on the coastal sand or rocky slopes where they benefit from the cooler temperatures and coastal fog, but others can also be found in the inland foothills and mountains, also with cooler temperatures. We find it is essential to provide them with afternoon shade in the Central Valley. Succulents require good drainage or they are likely to rot, but this is more difficult with our clay soil. These are planted alongside a set of steps where we created pockets in the rocks. This, together with the slope, helps with drainage.

We have had many successes growing native succulents. Cliff maids (Lewisia cotyledon) are very colorful, easy to grow, and are the first to bloom. Probably my favorite succulent is Palmer’s dudleya (Dudleya palmeri), covered with white and orange buds that are fascinating and continue for a long while before bursting into flower. The big white leaves of chalk dudleya (D. pulverulenta) contrast well with other succulents. The layer of wax that looks like a white powder, called farina, reduces water loss and protects the leaves from sun and wind. If the leaf is touched, this coating rubs off and doesn’t return. Rosette forms of succulents benefit from being planted at an angle to help water drain and reduce chances of rotting. Broadleaf stonecrops (Sedum spathulifolium ‘Cape Blanco’ and S. spathulifolium ‘Purpereum’), and wormleaf stonecrop (S. stenopetalum) are all at home tucked in the rocks.

Right: Chalk dudleya (Dudleya pulverulenta) with shriveled leaves. Credit: Patricia Carpenter

Right: Broadleaf stonecrop (Sedum spathulifolium ‘Purpureum’). Credit: Beth Savidge

As summer progresses the succulents will become dormant and require little water. It is difficult for us to resist pulling the declining leaves from the plants, but they help to protect them. Succulents are amazing—they can look a bit ratty or almost dead by fall but with the cool, wet winter and spring the shriveled leaves plump up, and plants flower again late spring into summer.

Desert Area

The hot south-facing desert area finally comes alive with an abundance of blooms throughout the summer. Visitors are always delighted with the variety in the leaves, diversity of blooms and the unique seed pods. The pink fairy duster (Calliandra eriophylla) and red zapotillo or Baja fairy duster (C. californica) are both winter deciduous, but also drought deciduous if stressed. These fairy dusters reliably provide color and interest, and the pods are a favorite subject in Beth’s photos. We are so fortunate for the past two years to have her recording the five seasons in our native garden.

Right: Red zapotillo (C. californica.) Credit: Beth Savidge

The 15-year-old Apache plumes (Fallugia paradoxa) and bladderpod (Peritoma arborea) thrive on this sloped environment, which receives an overhead watering about once a month to every six weeks during the summer, mimicking the occasional desert monsoons. These two plants both have interesting seed pods as well. The white-leaved big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) has an extensive root system to help to find water. It has grown so well in the desert area during these past dry years.

We grow three penstemons in this area, desert penstemon (Penstemon pseudospectablils), Eaton’s firecracker (P. eatonii), and Palmer’s penstemon (P. palmeri), all easy to start from seed. The desert penstemon has proven to be the best for us, long-lived and very showy. The hot pink blooms are indeed spectacular, usually covered with hummingbirds and bees. A choice new desert milkweed, beloved by all, is pine needle milkweed (Asclepias linaria) with white flowers. It is evergreen and responds well to cutting back when needed.

Right: Pine needle milkweed (Asclepias linaria). Credit: Beth Savidge

Many yellow flowers grow in California deserts and here are some of our favorites that we have planted. The turpentine bush (Ericameria lariifolia) has tiny aromatic bright green leaves that contrast with the numerous gray-leaved plants. I especially love the spent star flowers that remain after the bloom. The floppy prince’s plumes (Stanleya pinnata) use nearby plants as support. Palmer’s abutilon (Abutilon palmeri) has soft gray leaves covered with fine protective hairs. This plant often dies from winter frost but reseeds most years. And lastly, the bright yellow flowers of desert marigold (Baileya multiradiata), always covered with tiny native bees, just make us happy.

The white-flowered annual toluaca (Datura wrightii) reseeds abundantly each year but it is the desert California bluebell (Phacelia campanularia) that we really want to take over! Unfortunately, we have not yet found the secret of success—we only have a few plants each year. This is definitely not the blue expanse that we are envisioning. The best solution so far has been to tuck seeds under shrubs for pest and frost protection. Doubleclaw (Proboscidea parviflora) is a new annual for us with delicate pinkish flowers. We are sure it will do quite well based on another non-native of this genus that we pull out each year. Both make an interesting double claw when the seed pod splits.

Right: Palmer’s abutilon (Abutilon palmeri) has protective hairs on the leaves. Credit: Patricia Carpenter

In some of the other areas of the garden the cool season grasses are now golden and flopping, but in summer the desert warm season grasses are beautiful. Pat’s favorites are the side oats gramma (Bouteloua curtipendula) and alkali sacaton grass (Sporobolus airoides) which will grow with little water and seasonal floods. Mine are the purple three-awn (Aristida purpurea var. purpurea) that is beautiful backlit and swaying in the wind, and plains lovegrass (Eragrostis intemedia), that supposedly doesn’t do well in clay soil but has been just fine on the hot, sunny slope. We are always excited to find kingsnakes in the grasses and this summer there was a nice 4-foot beauty.

Summer Stomping

In the previous article we explored the ways the geophytes are able to survive the dry season with their underground storage organs. By summer the spring annuals and geophytes are now brown, and some are ready to be stomped to the ground. We discovered stomping when we started to grow perennial western blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium bellum) in the valley grassland area. At the end of the season our first year we cut them all to the ground when the plants started to look dry. That was work. The next year we decided to ignore them and let nature take over. That turned out not to be a good plan because the spent flower stalks all mostly remained upright right into the next winter when the new growth began. We had nice new growth mixed with the dead leaves and stalks that didn’t decompose because they weren’t touching the soil. The patch had grown even bigger by the third year when we decided to stomp during the dry season as animals would have. The stomped plants made a great mulch, the seeds and stalks touch soil and the new growth still emerges just fine each year.

After that we have experimented with stomping other annuals and herbaceous perennials. Timing is important as the plants need to be dry and may not be ready to stomp to the ground until fall. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium), California poppies (Eschscholzia californica), most annuals, and goldenrod (Solidago), are some of the other of plants we now regularly stomp. Yes, in our large, somewhat wild garden we can get away with stomped plants. If this is not desirable, woodchips on top make the garden neat again.

Garden Cleanup of Out-of-Control Plants

Eventually, gardens have plants that have been so successful that there are more than needed. If there is no problem with the plant reseeding, we simply pull or dig out the extras and chop them up onto the ground. But a few of our grasses are always trying take over and grow where they are not wanted. Since we keep all plant material in the garden, even those we don’t want, we needed a plan. Purple needlegrass (Stipa pulchra) is lovely but needs to be reduced by at least half each year. After it blooms it is generally very easy to pull out. Now we find a place or two nearby to make piles of unwanted grasses, yarrow (Achillea millefolium), and other out-of-control plants. The piles are usually a foot or two high at first and a yard or more wide. They are regularly stomped and maybe even covered with some woodchips. Since most seeds can’t reach the soil, they don’t germinate and the ones that are on soil can’t reach the light, so we have a bare area for a while instead of hundreds and hundreds of germinating seeds. It is important to do this before too many seeds have matured and dispersed.

Flowers and Bees

The summer garden is definitely not all dead looking and brown. It does still have flowers and color; California fuschia (Epilobium), buckwheats (Eriogonum), goldenrod (Solidago), and gumweeds (Grindelia) are abundant. One day in late July several years ago, I came upon a small group of bee experts who had been given permission by the owner to visit our native garden. A young man with a net was just beaming as he swiped and successfully caught many bees. Realizing my interest, he started to show me and identify his finds. They were all very excited to find such a variety of flowers at this time of year! I later counted about 90 species or cultivars blooming in our native garden, although some only had a bloom or two remaining. As these scientists were leaving and thanked me for the bees collected, they told me they estimated there were about 100 species of native bees in the garden based on what they had seen or collected and the diversity of plantings. Pat and I were the ones beaming for weeks after—and still are! Enhancing habitat for native bees and other pollinators was one of our primary goals.

Right: Great valley gumweed (Grindelia camporum) attracts many pollinators. Credit: Beth Savidge

My favorite quote by philosopher Sam Keen “Deep summer is when laziness finds respectability” reminds us to take a cue from the plants and slow down … and just maybe think a little bit about fall planting.

Resources

Beth Savidge photos of Patricia’s native and main gardens (2020, 2021)

California Native Plant Society Garden Ambassador profile of the Native Garden: Patricia Carpenter’s Davis Garden

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Nature Therapy from the Contemplative Garden

Winter 2022 Women’s hushed morning voices mingled with crashing waves and chattering crows. “The kettle’s still hot.” “Can you pass the honey?” Whoosh, crash, caw,

Responses