Contributor

Mediterranean1.The word conjures a variety of pleasurable images. Balmy, sunlit shores lining an azure blue sea; bowers of exotic flowers, their fragrance wafting on soft, warm breezes; whitewashed, thick-walled buildings with scarlet bougainvillea spilling out of secret courtyards; yellow ochre, red-tiled villages pierced by black green shafts of cypresses; palm-graced cities and villas luxuriating in lush verdure; intimate Andalusian courtyards cooled by the tinkle of water; or rich, flavorful food washed down with cool wine beneath the dappled shade of an ancient olive tree….These are images of a paradise that humans have been creating or seeking since the beginning of time. Mediterranean. Paradise. Eden!

The Mediterranean Region, surrounding the sea by the same name, has been sought after and fought over as long as history has been recorded. No other region of the world, except perhaps Hawaii or Fiji, evokes such powerful, seductive images of paradise. And of the four other regions of the world with mediterranean-type climates, only California approaches this same vision of paradise.

Recent interest in mediterranean gardens on the West coast has been spawned, in part, by the continuing need for water-conserving landscapes, and by a plethora of seductive books on the Mediterranean. Two conferences sponsored by Pacific Horticulture, Gardening Under Mediterranean Skies I & II, have raised the question, what is a mediterranean garden? Participants seeking answers invariably conjure up myriad images, influenced by examples from Spain, Italy, and Greece. The emphasis tends to be on plants, especially among gardeners and horticulturists—with lavender, rockrose, oleander, olive, roses, thyme, pomegranate, and rosemary as a basic palette, all well-suited to the limitations imposed by a summer-dry climate.

Surely there is more to a mediterranean garden. Such a narrowly horticultural view traps us in the belief that style and fashion in gardens is achieved merely by the selection of the right plants, whether mediterranean, English, or Japanese. What then is the context for a mediterranean garden?

I believe gardens evolve from a confluence of culture and climate. While the common denominator is climate, the gardens of Spain differ from those of Italy or Greece. The adaptation to the region’s climate comes from a cultural interpretation incorporating intellectual and spiritual thought and values. The similarities appear in outdoor spaces that provide for basic human needs: shade and cooling in summer, warmth in winter, aural and visual delights to contrast with the arid landscape beyond, and food prepared from a rich palette of edible plants native or adapted to the climate. The Italian hillside terrace garden mimics the Spanish carmen garden, just as the Spanish courtyard resembles the Greek peristyle court; all reflect cultural adaptations to climate, with variations in the detail and embellishment.

But what about California with its great cultural diversity, its wealth, and its heavy dependence on technology? Does a garden of California native plants qualify as a mediterranean garden despite the absence of olive, rosemary, and lavender? Is our addiction to a greensward bordered by mediterranean plants a valid model? What are the primary forces that might serve as the foundation for the design of a mediterranean garden in any mediterranean

climate?

The mediterranean garden is about relationships—between humans and the unique characteristics of the mediterranean environment, between our modern culture and historic traditions, between ourselves and the garden as an expression of our lifestyles and the fulfillment of the functional and design possibilities of the garden. The following summary—covering five primary considerations—can help guide the design of a mediterranean garden. Each will be expanded upon later, with specific reference to the California garden.

Personal and Cultural — A garden is a personal expression of the gardener or designer—a physical response to the need for space, privacy, retreat, and recreation, and to individual preferences for sensual qualities. This might include inspiration from historic precedents in the Mediterranean that adapt to our needs without being merely eclectic.

Climatic and Geographic — A garden is both a response to, and a reflection of, the larger landscape—its climate and microclimate, its topography, and its soils. In a mediterranean climate, this means that the design of a garden acknowledges the summer heat and aridity, limited rainfall, prevailing wind, generally alkaline soil and other characteristics, in order to provide for human comfort and enjoyment and for sustainability with limited resources.

Functional Design — A garden is designed as one or a series of outdoor rooms for a variety of year-round human activities (including gardening) that are permitted, even encouraged, by a mediterranean climate. That requires walls and edges, paving, shelter from sun and wind, vistas to the larger landscape, and provision of edible benefits for both humans and wildlife.

Sensual Qualities — A garden is a form of art, expressing the evocative qualities afforded by a mediterranean climate—light, smell, color, sound, feel, and spiritual refuge.

Regional Expression —A garden reflects characteristics of the regional variations within the mediterranean landscape, thus achieving a unique sense of place.

Personal and Cultural Influences

Of the five mediterranean regions, the Mediterranean Basin is unique in representing a collage of cultures. Fifteen countries on three continents (Europe, Africa, and Asia) embody distinct, yet interlocking, histories, religions, and beliefs. Thus, the cultural history of the Mediterranean runs deeply, intertwining spiritual beliefs with personal expression adapted to the climate. The other four mediterranean regions (South Africa, Chile, South and Western Australia, and California) all lie within a single country on a single continent; all are places in which aboriginal cultures have been dominated by immigrant explorers and exploiters, primarily from northern European cultures.

By stripping away our blind dependence on technology and seemingly unlimited resources, we can extract concepts from these gardens that may help us develop a more intimate understanding of how we and our gardens can adapt to the mediterranean climate.

We have much to learn from the earliest gardens of the eastern Mediterranean, even though they originated in a desert. These gardens were a refuge from the harsh, arid landscape and were expressions of a culture based on spiritual beliefs (Islam) or derived simply from patterns of irrigation, as in Egypt. To fully understand the meaning of the Islamic concept of paradise, one must try to appreciate the context: the landscape of barren plains, hostile mountains, heat, and glare from the merciless sun. In such a setting, cooling shade from a few plane trees and the sound of a babbling brook create a sanctuary for both body and spirit.

The basic elements underlying the Islamic garden include: relief from the desert wilderness; cooling shade from the sun; refreshment in the sight, sound, taste, and feel of water; greenness cooling to the eye; respite for the tired body; and refuge for the spirit, with the promise that the hereafter will be even more refreshing and comforting. The Koran emphasizes the garden as a symbol of paradise, with water, shade, and fruitfulness as it’s ideal components. The four rivers of paradise—pure water, milk, wine, and honey—form the basis of the quartered garden so characteristic of the Islamic garden.

Thus, form is given to the earthly paradise—the garden that followed the advance of Islam throughout the world. It is no small coincidence that people of that culture (and its offshoots) settled in either desert or semi-arid mediterranean climate regions along the shores of North Africa and Spain, in Mexico, and, finally, in California.

In our urban gardens we also have much to learn from early Greeks. Though not known for their horticultural expertise, they gave us a model that the Romans and Moors refined, that of the peristyle courtyard garden. Located at the rear of dwellings in dense city neighborhoods, this garden afforded privacy and refuge from the city as well as relief from summer heat. The Spanish courtyard and its contemporary forms can still serve these personal needs in urban California.

California’s cultural heritage is complex. Aside from the early Spanish missionaries and the recent influx from Asia and Latin America, immigrants have come mostly from temperate climates in northern latitudes. Early Anglo settlers rejected the architecture and gardens of their Hispanic predecessors. Garden and landscape ideals that they brought with them were forged in a moist, temperate climate. Supported here by artesian wells, their gardens celebrated a new-found paradise of tropical or subtropical flavor. The brown California landscape was denied as these gardens turned inward, typically ignoring views out toward mountains or sea.

This significant cultural statement is as nearly true today as a century ago. Coming west, Easterners encountered a landscape totally unlike their own—one whose scale was overwhelming, whose colors were unfamiliar, and whose arid climate was totally foreign. As Wallace Stegner observed: “Easterners are constantly being surprised and somehow offended that California’s summer hills are gold, not green. We are creatures shaped by our experiences; we like what we know, more often than we know what we like. To eyes trained on universal chlorophyll, gold or brown hills may look repulsive.”

Thus, our gardens and landscapes in mediterranean California tend to reflect landscape preferences imported from temperate zones. Gardens are considered in various ways: as settings for the house, to establish status and respectability; as “landscaped” yards; as plant collections; or as creative designs, often lacking spiritual or deep-seated traditions, or ignoring the determinants of the climate. Gardens often reflect the passion of people for plants, resulting in diverse and personal expressions with little recognition of climatic constraints. Californians have freely used money and resources to overcome the limitations of the mediterranean climate in achieving landscapes and gardens of a naturally wet climate.

The “drought years” of the late twentieth century focused attention on changing the way we design gardens and landscapes, but the effects have yet to become deeply ingrained in our culture. In an age of unprecedented wealth and consumption, we have yet to come to grips with living in—and adapting to—this mediterranean climate.

Climatic and Geographic Influences

The world’s mediterranean climatic regions are bonded by the following characteristics, which combine to distinguish them from among the world’s landscapes:

Latitude

- regions are between 32° and 41° north and south of the equator

Aridity

- relatively low rainfall with the bulk (more than 65%) falling in the winter half of the year (California is actually “more” mediterranean than the Mediterranean Basin, with about 80% of rain falling in winter)

Precipitation

- precipitation is primarily in the form of rainfall, varying from 10.8 inches (.275 meters) to 35.4 inches (.9 meters) yearly

- coastal fog and rare light snowfalls contribute to the precipitation in some areas

Humidity

- low summer humidity, especially in inland areas, creates high sun intensity due to clear, cloudless skies and the low moisture content of the air

- high evapotranspiration rates in inland areas, roughly twice as high as on the coast

Mild temperatures

- warm to hot summers and cool but mild winters, with only one month averaging below 59° F (15° C)

- sub-freezing temperatures do not exceed 3% of the total time

Coastal location & maritime influence

- all regions situated along the coast of oceans or the Mediterranean Sea

- all, except large portions of the Mediterranean Basin, are on west coasts

- strong, cold up-welling currents bathe coastal regions in cool marine air and moderate the winter temperatures, except for the Mediterranean Basin and South and Western Australia

Topography

- rugged mountains, frequently parallel to the coastline (except in Australia), influence and modify climatic patterns forming distinct rain shadows and microclimates

Vegetation

- a woody flora dominated by arboreal and compact, shrubby, evergreen, schlerophyllous plants adapted to climatic stresses of heat and aridity

- a well-developed annual and herbaceous (often bulbous) flora

Summer dormant vegetation

- a summer dormancy is induced by heat and lack of soil moisture, except in cool, foggy, coastal zones

Fire

- summer and autumn fires occur frequently as a means of renewing vegetative growth

These characteristics of our climate are unique and contrast with the temperate climate of the eastern US and northern Europe. However, our technical achievements and benevolent resources of water and power have given us the ability to overcome—even ignore—these climatic constraints. But with global warming and increasingly abnormal weather, the likelihood of an even drier mediterranean climate, coupled with undependable water resources and increasing energy costs, we must pay attention to these climatic imperatives in the design of our gardens and landscapes.

Functional Design for a Mediterranean Garden

As English landscape architect, Silvia Crowe, wisely observed, a collection of choice plants is no more a garden than a selection of choice words, a poem. In a mediterranean climate, the design of a garden begins by responding to the climate and the spatial needs of the garden users. Plants are selected to help fulfill functional requirements and to establish landscape character, among other things.

Spatial

The design of any garden begins with defining spaces for outdoor uses and functional needs, using a combination of structures and plants in the creation of “garden rooms” that take maximum advantage of the benign climate. Here, smaller may often be better; maximum comfort may be achieved by a garden that is compact–deftly designed to address the needs of the residents while minimizing maintenance and the consumption of water .

The design of interior spaces surrounded by buildings, or of courtyards defined by walls or fences—adaptations of the Greek peristyle or Andalusian courtyard—provide privacy, intimacy, and control of the microclimate. Such spaces are as relevant today as in old Mediterranean gardens. Though our houses are typically monolithic in form and surrounded by lawn, we can still create intimate walled courtyards eminently suited to our climate.

Microclimate Modification

The modification of microclimate through garden design can not only create comfortable outdoor spaces but also help conserve energy for houses, primarily in summer but in the colder months as well. Terraced gardens in Italy and Spain were oriented to capture sunlight in winter, storing heat in the walls and pavement for evening warmth. Welcome summer shade is achieved by the addition of vine-covered arbors, bosques of trees, and arcaded walls. Dense plantings can also mitigate cold coastal winds.

Water

Essential both for irrigation and its refreshing sound, water can be efficiently and effectively used in our semi-arid climate. Efficiency is achieved through the maximum use of pavements (including both hard and soft materials), the selection of water efficient plants, low volume irrigation systems, and subtle water features. In Spain’s Moorish gardens, the simplest water basin symbolizes a bubbling spring; its calm surface reflects the stars, joining the heavens with earthly paradise.

Except in drought years, we have taken for granted an unlimited water supply, supporting our propensity for lavish displays, whether in water features or floral extravagance. We need to develop a deeper appreciation for water, both as a source of refreshment and enjoyment, and as the live-giving basis for our garden plants.

Plants

Though we are tempted to begin a garden by planting favorite plants, the greatest long term satisfaction and benefit is achieved when plants are first selected and arranged to define spaces, modify microclimate, provide screening, and satisfy other design functions to give the garden its structure and form.

Selecting and placing plants in the right conditions of exposure and soil contributes to long-term success. Selecting plants that are well adapted to semi-arid conditions helps achieve a harmony in landscape character. Grouping plants with similar water requirements ensures compatibility and water efficiency.

Planting for diversity results in year-round interest in foliage, form, and color. Selecting plants that attract desirable wildlife (birds, butterflies, bees, and small animals) enlivens the garden to its full dimension and contributes to its ecological value within the surrounding community.

Structural Materials

Where possible and available, the use of natural materials of local origin—stone, gravel, decomposed granite, wood—reinforces the garden’s regional relationship and sense of place. A simple combination of a few compatible materials enhances plantings and connects our gardens to the regional context.

The rediscovery of the materials and techniques of rammed earth walls and soil cement paving links us with the history and evolution of Mediterranean gardens. Similarly, straw bale walls emulate the thick mud walls found in the Mediterranean while employing a recycled, renewable material.

Sensual and Ephemeral Qualities

Design that satisfies functional needs gives a mediterranean garden form and structure in response to climate, site conditions, and human activities. The sensual qualities give it spirit. That spirit combines the owners’ preferences—the enjoyment of certain plants, ephemeral effects, and daily and seasonal delights—with the landscape opportunities unique to the qualities of the mediterranean climate—light, fragrance, sound, and color. How contemporary “landscaping” cheats us of these delights!

Though the character of gardens will vary due to the subjectivity and personal nature of design, mediterranean gardens tend to be unpretentious, understated, and sometimes a bit rustic—not slick or stiffly formal. Consistent with the atmosphere of the climate, there is a calmness and softness created by natural materials and such plants as lavender, rosemary, and many California natives.

Such gardens need not be chaotic. Order and harmony can be achieved through informality or with simple geometry. A degree of formality played off informality heightens the effect of each, as in a pattern planting of lavender edged by a harmonious, but irregular composition of California natives or other mediterranean plants.

Light

The quality of light in a mediterranean climate offers distinct opportunities for garden design. The immutable, hard clarity of the summer sun (in smog-free areas) washes out yellow-green foliage and weak pastels. Intense primary hues and dark green foliage can stand up to such strong light. Deep, dark green, and blue-green foliage on the edge of the garden provides a backdrop against which brilliant reds, oranges, yellows, and silvery grays can be illuminated.

Silver to gray green foliage is common in the mediterranean plant palette and brightens the edge of paths and steps, even under moonlight. The light gray trunks of live oaks and cork oaks are magically illuminated in the low light of late afternoon. The golden light of evening and autumn afternoons transforms the trunks of madrone and manzanita into copper sculptures.

The morning light of coastal zones lends a muted softness to gardens. Fog creates soft-focus silhouettes of plants and sculpture—fleeting but memorable images enhanced by the brisk, salt-laden air and the pound of ocean waves.

Fragrance

A feature of the mediterranean plant palette is the prevalence of foliage high in volatile oils and aromas. Cooked in the heat of the summer sun, these fragrances offer additional ephemeral qualities: the sweet, pitchy smell of conifers; the pungent odor of sage, rosemary, rock rose, and bay; and the soft fragrance of lavender. the fresh smell of dry oak leaves in fall and the delicate aroma of new spring growth add to the array of fragrances. We are a visual culture, other senses dulled by our dependence on sight. In the mediterranean garden we can reawaken these senses by placing aromatic plants along a path or steps where foliage will be brushed. Or by placing sage, rock rose, and similar aromatic plants against hot, south-facing walls to heighten the release of their pungency.

Sound

We are inundated with the cacophony of urban life, from the noise of traffic to the blare of radios and television. The subtle sounds of a garden are often lost. As with fragrance, we can re-tune our ears to shut out the noise and listen to the ephemeral delights of a garden—the restrained bubbling of a simple fountain or small stream; the sound of birds and squirrels feeding; the

hum of bees on lavender; and the whir of

hummingbirds and dragonflies flitting about.

Even plants can be heard: acorns thumping on a roof, madrone bark crackling as it curls in the heat of late summer, and the crunch of dry leaves under foot. Similarly, gravel or decomposed granite paths and paving contributes a distinctive garden sound under foot. The sounds are there if we plan for them and take time to listen.

Color

Concepts of color in the mediterranean garden are linked to the seasons, the palette of plants, the light, and natural materials (stone, gravel, etc.). As with sound, color images (visual noise) inundate us daily. Thus, restraint and subtlety become virtues in the mediterranean garden.

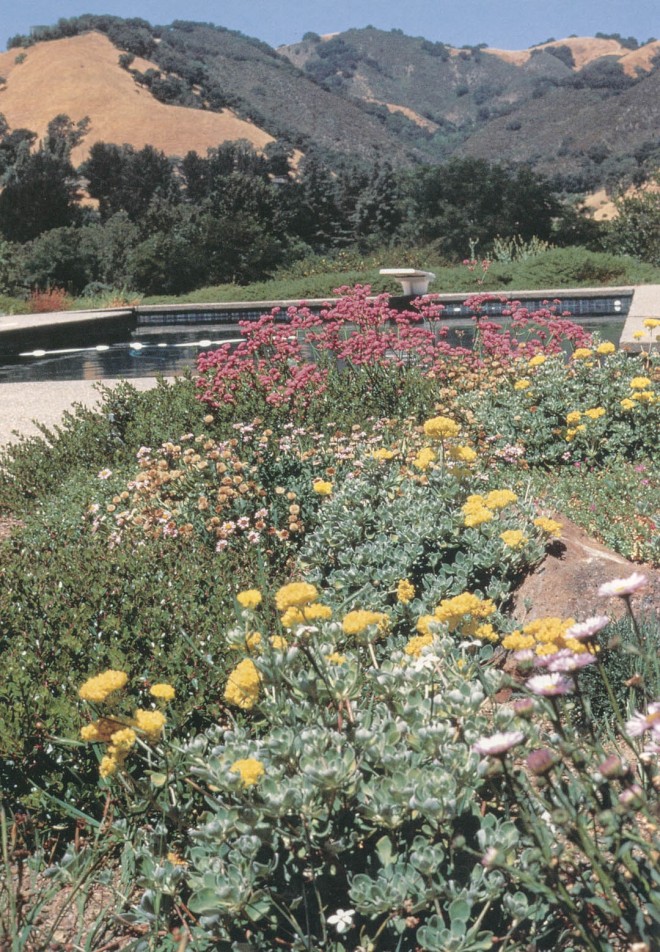

Taking a cue from the natural landscape, spring is the time of flowering and growth. Summer heat and aridity plunges many plants into dormancy—a reversal of seasons compared with temperate zones. Awakened by winter rains, dormant bulbs, annuals, perennials, and shrubs burst into bloom—redbud, narcissus, grape hyacinth, rock rose, manzanita, ceanothus, buckeye, poppies, iris, and many other mediterranean species. In tune with the seasons, the mediterranean garden can celebrate spring and early summer with displays of floral color, rather than attempting to provide color all year long. With summer and dormancy, flowering becomes more subtle and muted—lavenders, California fuchsia, sage, and the rich hues of summer vegetables like tomatoes, squash, and peppers. Planting in containers can extend the flowering season with limited displays in featured spots throughout the garden. As summer wanes, the softer grays and browns signal the arrival of autumn. With little fall color, we cannot compete with eastern forests, except for big-leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), black oak (Quercus kelloggii), and such compatible trees as Chinese pistache (Pistacia chinensis), persimmon (Diosporum kaki), or Washington thorn (Crataegus phaenopyrum). Fall and winter bring out the reds and greens—colorful berries of toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia), cotoneaster, madrone (Arbutus menziesii and A. unedo), and others against the rich green of live oaks, conifers, ceanothus, and viburnum.

Garden as Refuge

Since ancient Greece, the garden has served as retreat and refuge from the stress, noise, and confusion of daily life. From the Greek city garden at the rear of the house to the giardino segreto of the Italian Renaissance garden, the seclusion, quiet, and comfort of mediterranean gardens have lifted the spirit and refreshed the soul of men and women. Courtyards and enclosed patios oriented inward afford refuge from the outside world. Such gardens offer the benefit of an intimate relationship with the garden, its plants, special effects of light, color, and texture, and wildlife. In comparison, traditional expansive gardens that surround most houses are designed more for show or to establish status, than as a personal refuge. In the intimate retreat, the sensual qualities are magnified—the smells, sounds, contact with birds, insects and small animals, and the change of light and seasons.

Regional Expression

Finally, the concept of the mediterranean garden in California can be summarized as an expression of the qualities of the regional landscape. Beyond the similarities of landscape and climate, variations exist: cooler, wetter, and greener in the northern reaches; the cool, maritime coast; hot-summer interior valleys; and drier, near-desert, southern areas. By adapting the design of the mediterranean garden to reflect and express the colors, forms, and textures found in the region’s plants and landforms, among other visual qualities such as light and atmosphere, we can reinforce our sense of place; we surrender to the realities and uniqueness of the mediterranean climate and become rooted in it. Our gardens develop a sense of belonging, both visually and ecologically. Horticulturally, they fit the region and thus are easier to maintain and sustain.

And so, the mediterranean garden becomes a personal expression and interpretation of the special qualities and characteristics of the mediterranean climate and landscape. As participants in its design, its making and care, and its enjoyment, we become transformed and find ourselves adapting to the landscape, in harmony with our place in the world.

[sidebar]

1 The word mediterranean (lower case) refers generically to mediterranean-type climate, vegetation and the other features of the various Mediterranean zones of the world. Mediterranean (capitalized) refers to the geographical region of the Mediterranean Sea.

[/sidebar]

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses