Contributor

- Topics: Headline, Inspired Gardens and Design

It is a rare rainy day in Santa Barbara when I arrive at Isabelle Greene’s office. The low-ceilinged front room is softly lit with an overall patina of many years of use, filled with drafting tables, file cabinets, and a comfortable sofa. Adjacent is Isabelle’s library, inspiration spilling from the overflowing bookcases. We settle in at the central table for our conversation.

The early years

Revered as one of the most innovative landscape architects of our time, Isabelle’s career is grounded in the Western geography of the United States. Her early years were spent in Pasadena, at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains. Here, her grandfather and great-uncle were partners in the Greene & Greene architectural firm and influential in the burgeoning American Arts and Crafts movement, especially in California where their iconic Craftsman aesthetic has endured. Isabelle’s grandfather, Henry Mather Greene, is often erroneously cited as having imparted his aesthetic to his granddaughter, but according to Isabelle, the influence was indirect: “I can’t remember any conversations like that.”

Visiting her grandfather’s house as a toddler, Isabelle was exposed to good craft and superlative design—cool, dusky interiors with dark polished wood, the kitchen filled with light, and cool stone foundations. These early visits informed Isabelle’s aesthetic sensibilities and observational skills. When thinking about her grandfather’s garden she recalls “Strong, beautiful memories of venturing into his seemingly endless yard,” where she discovered “the magic of a great old pergola” draped with blooming wisteria and roses. “Grandpa believed in making all that met the body and the eye exactly right for the inhabitants,” she added.

“I think I was never without a love of plants,” Isabelle continued, recalling a family photograph of herself at around one-and-a-half years, stark naked in cowboy boots, holding a big watering can and watering the weeds. “My mother knew the names of plants because my grandfather would take her on walks in the evening, teaching her about them,” she said. “So naturally, I could name them, too.”

At one point, the family replaced their front lawn with wildflowers, which according to Isabelle her father thought was “a wonderful and eccentric idea.” She recalled walking amongst the head-high plants, “The brilliant petals at [my] eye level, the caterpillars a bit frightening.” Later, when they moved to another house Isabelle recalled planting “my two best-loved plants—a ‘Cecile Brunner’ rose and columbine.”

Hiking with her parents in Pasadena arroyos and camping in California’s mountains and deserts during those early years deepened what would become Isabelle’s life-long passion for the natural world.

An emerging career

Isabelle graduated from UCLA in 1956 with a bachelor’s degree in taxonomic botany and married botanist Bob Haller that same year. In 1957 the couple moved to Santa Barbara when Bob accepted a teaching position at the University of California. Isabelle began illustrating Bob’s research papers, a natural extension of her botanical studies and love of drawing. Her skills were in great demand by Bob’s colleagues as well, and under the name Isabelle Haller, she became known as a botanical illustrator. Her drawings appeared in a textbook that was later placed in Carnegie Melon’s permanent Collection of American Botanical Illustrators.

To hone her skills, Isabelle enrolled in art classes at UCSB where she studied Beginning Drawing with instructor Michael Dvortcsak. “[Michael] accepted nothing but truthful lines and kicked my butt until I let go of my tight, scientific style,” she recalled. “He told me, ‘Always make your mark forever’ and ‘if you don’t like it, pick up your pen and make another [mark].’ I learned not to be tentative, and never superficial.” An approach she later extended to her work in landscape design. When the Hallers divorced in the 1960s, Isabelle (née Isabelle Clara McElwain) adopted her grandfather’s last name.

Isabelle fell into a career in landscape architecture almost accidentally when she was invited to design a landscape for a friend’s medical office. From the start, she brought her powers of observation to creating unusual designs that often included native plants. In discussing her approach to the project she observed, “The sense and feeling of a space—I have been thinking about that for as long as I can remember.” She recalled seeing the surrounding mountains, their soft greys and greens: “I wanted to tie it all together.” This first job received a Santa Barbara Beautiful award in 1966 and, despite her lack of formal training, led to more landscape design work.

Citing her early influences, Isabelle told me she depended on her instincts, her experiences, and images she had absorbed from books: “Roberto Burle Marx gave me the freedom to spread color. From James Rose, a subtle architect, I gained a lyrical sense of passage from outdoor to indoor. And I had a Japanese book, too.”

Isabelle Greene & Associates

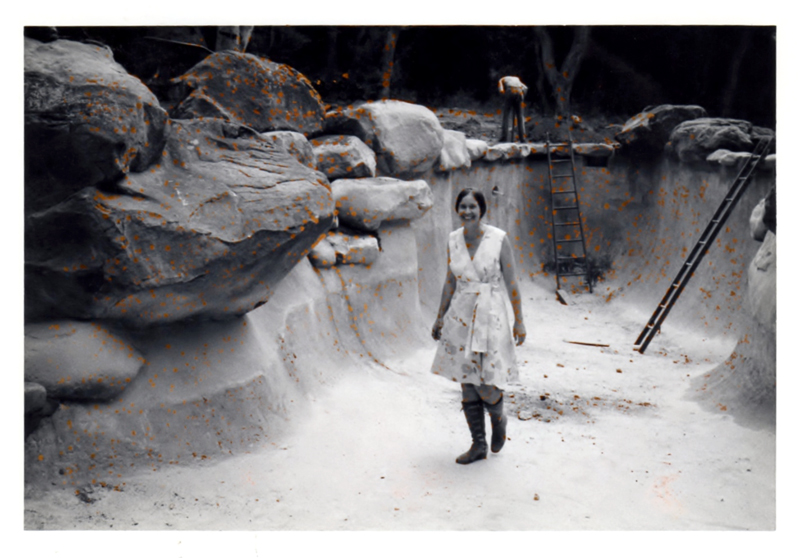

In 1972 Isabelle received a significant commission to design a naturalistic swimming pool for the Lovelace garden in Santa Barbara. Set within six acres of oak woodland, she boldly envisioned the pool as an extension of the garden, rather than the house, an innovation that captured international attention.

At the time, Isabelle wasn’t licensed as a landscape architect and had neither the time nor the money to pursue further schooling. “My fright about the Lovelace pool was so great, I . . . employed a licensed landscape architect to coach me in my work.” Michael Wheelright reviewed her plans, while insisting that Isabelle pursue the licensing exam. It took Isabelle seven consecutive years to pass the entire four-day exam by knocking off a section or two with each try. An approach she counted as a blessing: “I wasn’t trained to think in styles and principles that shut off intuition. [That] freed me from a lot of formulaic work.”

In addition to public gardens and botanical institutions, Isabelle has worked with hundreds of clients on residential designs, in a wide range of styles. Her designs were naturally drought tolerant and sustainable, most were grounded in California’s mediterranean climate and incorporated native plant communities long before the practice was widely accepted.

Developing a relationship with clients is essential to Isabelle’s design process. Prior to visiting a potential job site, new clients are invited into the office—“our turf”—to get acquainted. Isabelle asks probing questions like “How do you like to live?” and “What do you think about?” and shows pictures to determine client preferences: “Some people hate geometry, others like clean lines. Some people like color. A mortuary wanted a restful place.” Every job is unique and specific.

Isabelle’s work is intended to evoke sensations. She described one project where big vertical rock slabs were placed with small plants nestled at their bases to emulate “the feeling I get from the craggy cliffs of the Grand Canyon.” Begun in 1982, the Valentine garden is another one of Isabelle’s renowned projects. Designed in a strictly Modernist style and built on a steep slope, the main portion of the garden was viewed from above and referenced what she described as “miniaturized farm patterns seen from above in a plane.” (Pacific Horticulture published the first photos of the then barely completed garden in the winter 1984 issue.)

Designs that endure well over the years are a hallmark of Isabelle’s work. “Enduring spaces are comforting,” she observed. “I try to design so things are working well for as long as possible. I love it when the owner wants me back for further adjustments.” And while it was painful at first, Isabelle has learned to turn away from projects that have been neglected or demolished. “What makes me angry is when value is lost,” she remarked. “If you own it, be ready to take care of it.” Isabelle has maintained relationships with some of her clients for decades; one of her most long-lasting associations has been with the Lovelaces, with whom she has worked for almost fifty years.

Public gardens where Isabelle’s work may be viewed include the Theater Garden at Ganna Walska’s Lotusland in Santa Barbara, which she recreated in the 1980s; the Casita del Arroyo Demonstration Garden in Pasadena—now strayed from its purpose—and further afield, the Silver Garden at Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania.

Recognition

Isabelle has accrued many accolades since the 1966 Santa Barbara Beautiful Award. In 1999, she was Fellowed by the American Society of Landscape Architects. The title of this article is borrowed from a retrospective show of Isabelle’s work, held at the University Art Museum at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2005. And in 2009, she received an Award of Distinction from the Association of Professional Landscape Designers.

Isabelle received the Heritage Oak Lifetime Achievement Award from Santa Barbara Beautiful in 2014. In August of 2017, the Lovelace garden was added to The Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS), an honor that includes complete archival documentation in the Library of Congress. Later that year, Isabelle was commissioned to create a historic garden for the Gamble House, a public exemplar of the architectural work of her forebears, Greene & Greene. In addition to these honors, Isabelle’s love of California’s wild landscapes has drawn her to become involved with green building and landscaping at the community level.

As I gather my things to leave, Isabelle mentions that, while the Lovelace’s house was spared, its beloved garden was washed away in the January 2018 debris flow in Montecito. She is working on its restoration and is grateful for the HALS documentation that has been an invaluable reference.

Now in her mid-80s, Isabelle Greene, botanist, artist, landscape architect, and activist has much to teach us. Inspired by the natural world and the sensuousness of tactile objects and human emotions, over and again she referenced her love of hiking in the mountains, the simplicity of the desert, and swimming in the ocean. “It’s a love I need to express,” she concluded. “I feel myself totally connected to the larger universe and I am not at liberty to disregard any of the laws of nature.”

Responses