Contributor

- Topics: Archive

At a recent board meeting for a Pacific Northwest horticultural organization, the world-wide celebration to honor the 300th anniversary of Carl Linnaeus’s birth was announced. From the looks on some of the faces in the room, the bearer of the news would seem to have been speaking Latin. Although experienced gardeners rely on a system of classification developed by Linnaeus in the mid-1700s, his name is still unfamiliar to many self-taught gardening veterans. With the tercentenary celebrations about to begin, we hope that will soon change.

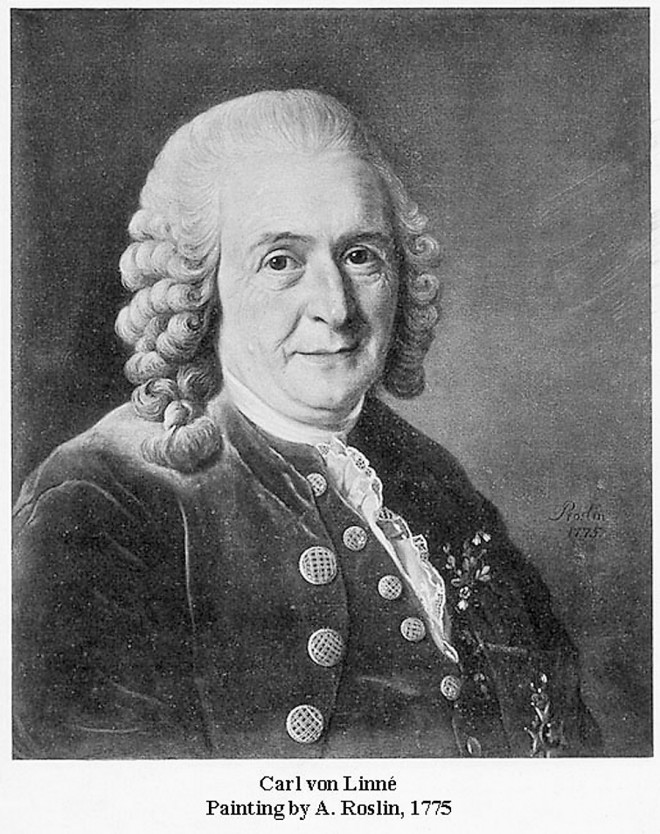

Named after the then reigning king of Sweden, Carl Linnaeus was born in May 1707, in Småland, a province in southern Sweden. His surname was chosen by his clergyman father, in honor of a tall linden tree (Tilia sp.) that stood close to his farmhouse. In recognition of his great service to Sweden and science, Linnaeus was knighted in 1757 and assumed his name as a nobleman: Carl von Linné. Today, von Linné is often referred to as the “Father of Taxonomy.”

During his school years, Linnaeus’s teachers believed that it would be impossible to reconcile Carl’s dislike for scholarly studies and his obsession with plants, so they urged him to become a tailor or a shoemaker. However, through a generous offer from the family doctor who recognized Carl’s potential, he was able to avoid cobbling and continue his studies in physiology and botany. At twenty-two, Carl traveled north to the University of Lund to study medicine. While at the university, Linnaeus had the good fortune to room at the home of a Dr Stobaeus, and often studied, by candlelight, the doctor’s personal library and museum of birds, shells, minerals, and dried plants. Linnaeus eventually left Lund and went to Uppsala, a larger university, considered then to be the center of Swedish intellectual life, and the home of a vast library and national botanical garden.

Linnaeus journeyed to Uppsala with little money and lived hungry for a summer, while devouring the wealth of information embodied in the collections of the school’s garden. As he was intently studying in the garden, a clergyman noticed Linnaeus and struck up a conversation about plants. This clergyman was Olaf Celsius (of the Celsius scale for temperature measurement). Apparent to Celsius that Linnaeus was no ordinary student: he invited Linnaeus to his home and offered him a room. For the next few years, Linnaeus attended classes at Uppsala, studied Celsius’s library, and began writing about the sexual characteristics of plants. Upon completion of this book, Linnaeus showed it to Celsius and his friend Olaf Rudbeck (of Rudbeckia fame), a botanical scholar. Impressed with his work, Rudbeck appointed Linnaeus his assistant. Upon Rud-beck’s retirement, Linnaeus was promoted to professor of botany at Uppsala.

Linnaeus’s most notable work, Systema Naturae, was first published in 1735. In it, he classified plants based on their sexual parts, upsetting many who criticized the book for its “sexually explicit” nature— some 200 years before Georgia O’Keefe made similar waves with her paintings. Linnaeus’s subsequent publications used the number and arrangements of stamens and pistils within the flower to group plants into classes, which were then divided into orders, genera, and species. Although Linnaeus’s system was not the first to use this “binomial nomenclature,” his was the most consistent and was presented at a time when the need for a workable naming system was urgent, due to the large numbers of plants and animals that were being brought back to Europe from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Linnaeus’s system was so widely accepted that even his greatest ideological opponents could not find flaws in his classification system.

In Linnaeus’s view, the various species of organisms had common traits that would allow them to be grouped into categories called “genera” (a word coined by Aristotle for a group of similar organisms). What Linnaeus added to the works of Aristotle and others was the gathering of these genera into higher taxonomic groupings (in Greek, taxis meaning order, nomos meaning law or science) that were also based on the organisms’ shared similarities. Think of it as an organized garden closet: all the weeding tools go in one bucket, all the Y-stakes in a tangled lump on the right, and the gloves on the shelf on the left; but within the glove shelf, there may be sections for small, medium, and large gloves, or for leather and cloth gloves. If there is a system in place, it is much easier to keep track of things. Thus, for our purposes, we might think of Linnaeus as an eighteenth century closet organizer.

As Linnaeus originally developed it, the ranking order was as follows: Kingdom-Phylum-Class-Order-Family-Genus-Species. To demonstrate, here’s how this system classifies two of our favorite columnar conifers, blue Italian cypress and ‘Wilma Goldcrest’ Monterey cypress. All plants belong to the Kingdom Plantae; within that kingdom there is the Phylum Pinophyta. Within that phylum is the Class Pinopsida, which holds the Order Pinales and the Family Cupressaceae. Much of these higher classifications are used only in academia; however, knowing plant families is instrumental in learning new plants. Both of our conifers are in the Genus Cupressus, but these two similar, but clearly different, plants part ways here. The Italian cypress is the Species sempervirens (meaning evergreen) and the Cultivar ‘Glauca’ (for its bluish foliage). ‘Wilma Goldcrest’ cypress is the Species macrocarpa (producing large seeds) and the Cultivar ‘Wilma Goldcrest’. So, the proper names for these two conifers are: Cupressus sempervirens ‘Glauca’ and Cupressus macrocarpa ‘Wilma Goldcrest’. These names draw a map to the same plants every time and avoid confusion along the way.

Further taxonomic distinctions below the level of species may tell us more about a plant or how it came into existence. Naturally occurring variations within a species may be identified as a varietas (abbreviated “var.”), a subspecies (“subsp.”), or a forma (“f.”). ‘Wilma Goldcrest’ is an example of a “cultivar,” which is a contraction for “cultivated variety.” Plants so named are propagated by humans to maintain specific characteristics, usually for ornamental or agricultural purposes. There are many rules regarding the use of italics, capitals, capital italics, quotation marks, and abbreviations, as well as years of pronunciation alterations and aberrations to consider. Taxonomists are constantly endeavoring to better understand the plant world and may reclassify plants based upon further research—now almost totally the result of DNA analysis.

With the help of this binomial nomenclature system, the obsessed garden consumer can be assured (assuming the plant is properly labeled) that the Albizia julibrissin ‘Summer Chocolate’ that we just traded our first-born child for is genetically the same plant as the Albizia julibrissin ‘Summer Chocolate’ ravaged by last winter’s cold weather in the front border. Wherever we go in the world, when we talk to other gardeners about Albizia julibrissin ‘Summer Chocolate,’ we will be speaking the same language and talking about the same plant. Linnaeus brought us a common language so that we might share a common understanding of the plants we love

Responses