Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Inspired Gardens and Design

Very rare flowers, however beautiful, are not considered desirable material for gardens, the scarce and unfamiliar being favoured only by vulgar and ignorant persons.

Joseph Conder, Landscape Gardening in Japan (1912), quoted by Christopher Thacker, The History of Gardens

Western observers are so impressed by the beauty, exoticism, and precise maintenance of the Japanese garden that they rarely attempt to understand the ideas behind the forms. As a result, from the late nineteenth century on, waves of japonaiserie have washed upon European and American soils, bearing with them the motifs and the look of the original but little of its substance. To learn from the Japanese garden, however, we must surpass mere appreciation and seek the intentions and ideas of the garden makers.

When we think of gardens in the West, we tend to focus on the plant, the tree, and the flower. But in traditional Japanese gardens it has been impossible to separate the garden from its supporting architecture. Space is treated as a continuum in which only a portion is roofed, with the remainder left open to the sky. In many respects the pavilion or temple is never the real subject of view, but serves instead as a sheltered space or bridge between two or more gardens. One does not look at the building, but instead sees through it. The view may be diverted momentarily by the furnishings, but the eye ultimately comes to rest in the garden beyond.

It is also significant that the traditional wooden architecture of Japan could modulate environmental conditions, but it could not really control them. A social contract allowed that summer heat was more troublesome than winter cold, so the house was conceived as a summer pavilion. In winter, due to the insulating properties of the thick thatch roof, the interior of the dwelling could be colder than the outdoors. Hence, viewing the garden from the transitional space between garden and house — the veranda — presented no considerable problems of physical discomfort.

While nature was accepted as the norm, and life was conducted within it, traditional Japanese design certainly modified how nature was perceived. Here the Japanese distinguished, albeit implicitly, between the physical and the psychological aspects of environmental perception. While one could build, one might also suggest a presence through implication alone. A Japanese proverb tells us that a whisper can be heard when a shout cannot. By extension, complete silence at times can communicate more effectively than a great clamor. This is our first lesson, then, from the Japanese garden: the effect of silence in a world filled with noise.

Silence and Void

One should not take the idea of silence too literally. We usually conceive of silence as the absence of sound, when it might better be defined as the absence of external sound. It is said that even in conditions of pure silence we would hear our heart beat and the flow of our blood. But the physiological dimension is only one that bears on our perception of place. We need also to consider the psychological dimension. Thus, the concept of absence throws us back on our own devices, forcing us to consider what is present and what is lacking in a place. In its seeming passivity and its reduced stimuli, the visually quiet garden engages us and draws us within. As a whisper can be more effective than a shout, so a void can be more powerful than an object.

By removing trees to create a sacred void, the planners of the high shrines at Ise fashioned a zone of silence within the natural order of the forest. The Shinto religion considers all space as enriched by the presence of the kami or deities. The presence of a deity can be manifest in unusual topographic or botanical features, their distinct characteristics suggesting a sanctified presence. Mircea Eliade, in The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, explains that the homogeneous, unarticulated space of the world holds no ultimate meaning; for tribal peoples it is a resource and a given. But as heterogeneous, religious space is created by manipulating the formal characteristics of the site, meaning emerges and space truly exists for the first time. The wooden shrines at Ise, of which there are about 225, are the architectural focal points and the means by which the uniqueness of their forest site is heightened. But the primary act of placemaking derives from selectively removing trees from the great cryptomeria forest that covers the land. Design, which by definition must disturb an existing order, at Ise takes the form of removal, clearing a place in the forest in the geometric figure of the rectangle.

Presence is further defined by lining the ground with gravels of different colors and sizes, finer and whiter as one moves toward the center. In the case of the Inner and Outer Shrines at Ise, the most sacred in all of Shinto, fences arranged in a concentric order mark the levels of sanctity, although the upper parts of the structures are always visible above the fences. As in the temples of ancient Greece, ordinary mortals do not enter the buildings; emphasis is instead thrown back on the site itself. The buildings and their contents have been reconstructed in the same form every twenty years, more or less without interruption, since the fifth century. Thus, two cleared sites always co-exist side by side: one vacant rectangle of gravel abuts one currently occupied by wooden fences and structures with thatched roofs. The gravel field of the Shinto shrine evolved into the yuniwa or formal courtyard, which in time became an element of imperial architecture and Zen gardens, reappearing periodically in Japanese garden design.

Focus

Building upon the presence of silence and absence, the dry gardens (kare sansui) of Japan provide a convenient model for examining the related lesson of focus. At a perceptual level it could be said that the use of stone and gravel and shrubs in such gardens is simply an intelligent manipulation of figure and ground: features of the surrounding “field” are distilled to rivet attention on the rocks, gravel patterns, or shrubs. This reading is too simple, however.

Japanese gardens rarely provide a single focus, but instead offer multiple foci and, more importantly, a set of shifting patterns and relationships — even if the field appears to be static. These gardens seem to acknowledge the saccadic movement of the eye — ever moving, never quite at rest. As the cathode ray tube reads and projects a television image, the eye scans the field of the garden within the limits of its two-degree cone of acute vision. Although the garden appears to offer little information, the moving eye and the brain to which it is attached enhance the sense of the place by manipulating the relationships among their constituent parts.

The fifteen rocks that comprise the stone garden at Ryoan-ji in Kyoto do not move; neither does the meditator stationed on the adjacent veranda of the temple hall. The contrived relationship of the stones to one another (one hesitates to use the word composition as being aesthetic alone) precludes seeing all of them at the same instant. And yet, while not visible, the presence of those other stones is felt. One may think of the stone as a stone; the stone as a metaphor; or the stone as a conceptual bridge for linking the here and now with places, ideas, or meditations in other dimensions. In this sense vision and focus fall not upon the stones but through them. As a result the finite may become infinite, and prosaic concepts of dimension and boundary are rendered invalid.

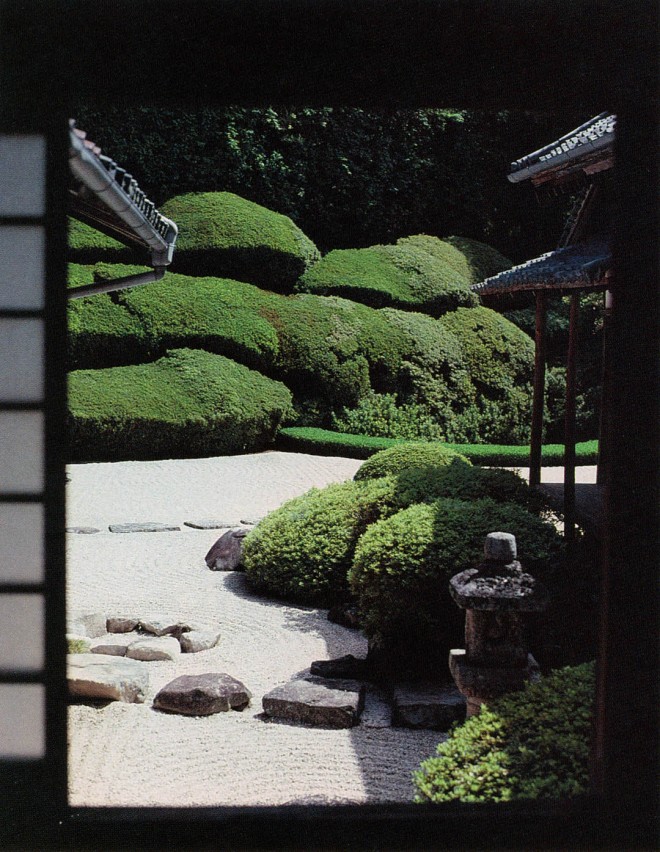

Rocks were not always the subject of the dry garden. At Shoden-ji in northern Kyoto clipped shrubs served as stones might, their rounded forms soft counterpoints to the geometry of the garden and the surrounding walls. The balance was not always in the neat domination of gravel over shrub, however. The principal garden at Daichi-ji is a garden of azalea hedges, maintained as a smooth, flowing form anchored by more geometrically sheared terminals. At Shoden-ji, one looks at the hedges against the gravel of the ground plane; at Daichi-ji, one looks into the hedge itself.

Apparent Space

Shoden-ji also uses a design tool often found in the Japanese garden as a means of increasing its apparent space: shakkei or borrowed scenery. If the field of Ryoan-ji can be rendered limitless through concentration, the field of view can also be increased by manipulating how the surroundings are read. In classical examples of shakkei one creates a garden of foreground features, then screens unwanted elements of the middle ground and utilizes distant scenic elements such as mountains as a background to the garden. Crucial here is the treatment of the middle ground: it must be strong enough to establish a believable limit to the garden and yet smooth enough to link foreground and distance in a comprehensible whole.

The rear garden at Entsu-ji employs the most direct application of borrowed scenery, a narrow hedge establishing the limit between garden and distant view. Tree trunks on both sides of the hedge use verticals to fashion a visually permeable screen woven together by the horizontal line of the hedge. In contrast to the foreshortening of Western perspective, the Japanese acquire spatial depth by layering two-dimensional planes. The hedge and trees of Entsu-ji create space in just this way, a technique also employed in the woodblock print, where layers of flat, overlapping forms substitute for the converging lines of perspective. Stronger still is the sense of landscape borrowing at Raikyu-ji in Bitchu-Takahashi, whose central stone mimics the general shape of the distant mountain. In our minds, the mountain is large and the stone is small. In our view, the stone is large and the mountain is small. This apparent conflict between what we see and what we know creates a bond between the two phenomena and an ambiguity that has no real resolution.

In the garden of Joju-in, a sub-temple of Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto, the landscape gardener Kobori Enshu forcefully manipulated the sense of space by positioning two stone lanterns in such a way that the repetition of their form created a link from the inner temple garden to the vegetation of the distant hillside beyond the ravine. The use of reference and replication compounds the ties between near and far and creates a more cohesive bond, or what architectural historian Teiji Itoh has described as a more aggressive “capturing” of the view rather than merely its use as a passive backdrop.

Unlike the contemplative Zen gardens, later gardens (certainly from the seventeenth century on) reintroduced the moving human figure into the landscape. Garden design utilized an almost choreographic aspect in which the effect of the space was exaggerated through sets of contrasts. The impact of a borrowed view could be heightened through restriction and then release, similar to the hide-and-reveal of eye-catching structures and specimens in the English landscape garden. The Imperial Villa of Shugaku-in, set on a hillside in northeastern Kyoto, is the supreme example of its type, its splendid panorama revealed only after ascending the slope within a claustrophobically narrow corridor bounded by tall hedges. In contrast to the restrictive enclosure experienced in mounting the staircase, space seems to explode as the landscape is opened to view.

Simplicity by Compression

Behind many of these design principles, and informed by religious and philosophical underpinnings such as the tea ceremony and Zen Buddhism, is a conception of a simple expression as having compound dimensions. In the West we tend to regard simplicity as the product of reduction; that is, we achieve simplicity by leaving things out. For example, early in this century the Austrian architect Adolph Loos could formulate an architecture in which the unnecessary (ornament) is discarded in order to focus on what is primary to architecture, in this case, space. Much of the argument against Modernist architecture has attacked just this tendency: Modernism leaves out aspects of architectural experience that are critical to enjoyment and appreciation, among them sufficient architectonic devices to suggest scale, ornament, and the textures necessary for continued visual interest.

Simplicity in Japan, on the other hand, has been conceived as the compression of complexity into an apparently minimal form. Examining the interior of a typical tea house, one finds a structure generated in three-dimensions by the standard one-by-two-meter ken grid developed from a module of the grass tatami mat. But the grid is never easy to discern in the completed structure, even in the pattern of the mats alone. The pervasive rusticity of the teahouse, borrowed from the rural farm dwelling, has blurred the grid almost to extinction, and its rigidity is further undermined by the seemingly random placement of elements such as the windows and doors, the ceremonial alcove (tokonoma), and its principal pillar. Even the crude texture of walls and structure are deceptively simple: the golden straw used as a binder and the grain of its wooden members provide a soft, visual excitement to equal, in its muted beauty, the kimonos of the participants and the implements of the tea ceremony.

The environment can be simple and yet not simplistic, developed from compression and enrichment of the simplest structural elements. The clay boundary wall at Ryoan-ji, stained by time and wear and centuries of repair, is as much a cultural monument as the rocks of the garden. During restoration of the tea houses at the Katsura villa, the dirt that plastered the walls was carefully brushed off and saved for the replastering. If lowly earth is so highly regarded by the Japanese, consider the cultural significance of making gardens.

Here we can see the intersection of many of the lessons noted above. In simplicity, in absence, in compression, in focus one can reveal aspects of the world that slip by unnoticed under the normal, complex conditions of our daily lives. The garden can become less the injection of new plants or objects into the old or new setting than the old setting re-seen as a new setting, with new objects and new relationships articulated by design. Rather than burdening landscape architecture with the role of court jester or provocateur, the deceptively simple garden or plaza directs responsibility back toward the human being for whom the garden has been created. This may be the most profound lesson we can learn from the Japanese garden and from Japanese aesthetic thought. Should we conceive of the environment as a splendid place in which existence is revealed to a passive human? Or should we think of the environment as the means by which one learns not only about that place, but simultaneously about oneself in the world?

[An earlier version of this article appeared in Arkkitehti: The Finnish Review of Architecture, Number 3, 1989.]

Responses