Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Green Gables, the seventy-five-acre Fleishhacker estate in Woodside, California, represents a time-capsule glimpse of an era of country estates built by wealthy Californians in the early twentieth century. Mortimer Fleishhacker, a prominent San Francisco banker and philanthropist, and his wife Bella commissioned Charles Greene, of the famous Pasadena architectural firm of Greene & Greene, to plan their summer home and garden. Green Gables survives today little changed since its construction nearly a century ago. Few such estates survive California’s changing landscape, especially in the north. Its recent dedication to The Garden Conservancy under a conservation easement ensures this legacy will continue in perpetuity.

Green Gables is a unique ensemble of architecture and garden that, according to Professor David Streatfield, echoes vestiges of both England and Italy. It represents the largest and most challenging commission of architect Charles Greene, who, with his brother Henry, were most notable as the preeminent Arts and Crafts architects of the early 1900s. For Charles, Green Gables departed from the Arts and Crafts style, both in character of the architecture and in the size and extent of the landscape.

Although the estate appears today as a single harmonious and unified ensemble, it was built in successive stages between 1910 and 1929 as parcels were added and plans evolved for the gardens. The site on the San Francisco Peninsula commands an expansive view to the south and west toward the Santa Cruz Mountains, a view little changed since Charles Greene first sat on the barren hill contemplating his challenge.

Design Inspiration

After a trip to England, the Fleishhackers wanted a house reminiscent of an English thatched-roof country house. Charles had also returned from a year in Great Britain, and stood ready to explore new architectural forms based on what he had seen abroad. In addition to the vast scale of the site, his challenge was to integrate that English architectural style, which was better suited to a moist climate, with California’s summer-dry, mediterranean-type climate, where the scarcity of water and the summer dormant vegetation posed a serious fire danger. His solution was ingenious. He designed a softly curving roof clad in redwood shingles that were steamed and bent to mimic a thatched roof. (As the house was being built, some of the gables appeared green to Mrs Fleishhacker, inspiring her to call the property “Green Gables,” a nickname that stuck.) In creating the soft, buff-colored walls to echo the tawny, summer-dry California hills, he employed a new material called gunite; now commonly used for swimming pools, gunite is a mixture of cement, sand, and water that was sprayed onto the forms for the walls.

The subtle beauty of the estate begins with the approach to Green Gables from the nearby public road on an understated, inconspicuous driveway bordered by low, dry-laid, fieldstone walls. The tree-lined drive winds in gentle, sinuous curves through a pastoral, park-like landscape of native oaks and grassland. The drive enters a shady forest and skirts the north and west sides of the central hill, with views down to a small lake that serves as a reservoir, before arriving at a large irregular motor court in front of the main house. It is only at the end of a pleasant drive through the rural landscape of this country estate that the stunning house and garden are revealed.

Main House and Formal Garden

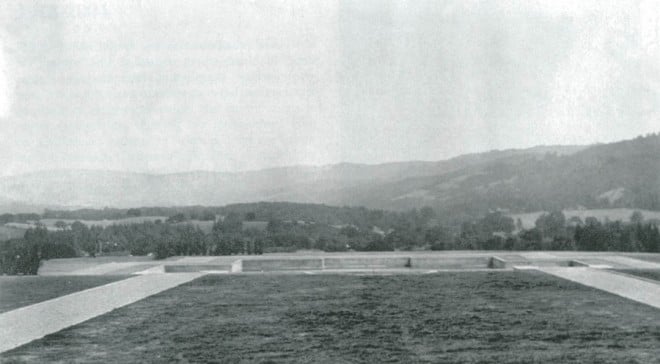

The house was sited below the crown of the hill and centered on a huge old valley oak (Quercus lobata) that was to shade the two-story house and its broad viewing terrace on the south side. The enormous, sculptural tree established the axis of the garden beyond. (That tree has since died and a new oak, Quercus muehlenbergii, has been planted in its place.) The terrace, paved with yellow Carnegie brick, sits above two shallow turf banks and overlooks a turfed parterre à l’anglaise and the distant view of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Below the terrace, the turfed parterre forms a simple plane of fine textured green, which contrasts with the strong silhouettes and coarser textures of the distant landscape and the informal groupings of trees that frame the view. Originally, the edges and corners of the lawn area were planted to frame the view with large shrubs, a number of tall, vertical Lombardy poplars (Populus nigra ‘Italica’), Atlas and deodar cedars (Cedrus libani subsp. atlantica and C. deodara), and a cedar of Lebanon (C. libani), with their blue gray foliage reflecting the blue haze in the distance. The poplars are long gone, but the cedars, large camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora), and English laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) remain.

Two gravel paths break the lawn into three panels and lead to a T-shaped lily pond at its far end. Water lilies break the surface of the lily pond, but leave plenty of open water to reflect the house to the north and the aged, sculptural trees at either side.

Roman Pool

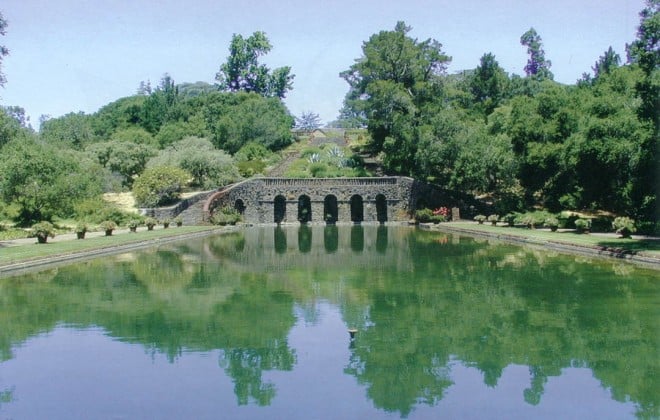

The parterre culminates in a brick balustrade at the crest of a steep drop, from which the Roman Pool is dramatically revealed sixty-five feet below. Two grand and gently curving stone staircases, separated by a planting of succulents and other dry landscape plants, descend to a landing at another stone balustrade atop a high retaining wall. Immediately below is an arcaded grotto at the near (northern) end of the pool.

The long Roman Pool (60 feet by 300 feet) and its freestanding arcade at the far end are reminiscent of the pool at Hadrian’s Villa. The tall stone arcade evokes the spirit of a Roman aqueduct. The pool is bordered by gravel paths and glazed ceramic pots designed by Greene. Atop the arcade are ceramic pots in a different style but also designed by Greene. (Elsewhere in the garden are many other ceramic pots, which Greene designed as the last phase of his work in 1933.)

Three types of stone from local quarries were used in the construction of the stairway, grotto, and arcade. Flagstones from Napa County pave the landings and the seats at the foot of the stairs. Large brown field stones form the steps and the base of some walls, and medium-sized field stones were used in the principal part of the walls. Small, chip-like, red chert stones were used for the copings, the arches in the grotto, and for large flower-pots located at the head of the stairs, on the principal landing above the grotto, and at the bottom of the lower flight of stairs.

A hidden feature in the garden is a small lawn bordered with olive trees and succulents; this lies to the east of the upper stairway that descends to the Roman Pool. Sometimes referred to as Granny’s Garden, it is thought to have been a favorite hideaway of Bella Fleishhacker.

East Terraces

The east slope below the main garden parterre is graded into two terraces. The upper terrace is composed of dry grass and the lower terrace contains a long allée of thirty-six Camperdown elms (Ulmus glabra ‘Camperdownii’). A long pathway with several flights of steps crosses the northern ends of these terraced slopes extending from the entry driveway and a lane of old redwoods below the entry drive. The lower section of the gravel path is lined with a mixture of white oleanders (Nerium oleander), Italian cypresses (Cupressus sempervirens), young Italian stone pines (Pinus pinea) and a variety of shrubs. These recent plantings reinforce the long axis of the walk.

A mossy brick walkway extends down the Camperdown elm allée toward the south and ends in a gravel path flanked by two old iron benches. At the northern end, across the cross-axial walk, a gravel path edged in field stone extends through a woodland of oaks and other trees down to the driveway northeast of the house.

An intermediate terrace lies between the elm allée and the upper main garden. This terrace is not irrigated and consists of dry grass that is mowed in summer. A small frame building sits at its southern end. Built for Bella Fleishhacker, an accomplished artist, it was called Bella’s Studio. A large window faces north along the terrace and provides illumination for the interior of her painting studio.

Swimming Pool

At the top of the hill, above the motor court and house, is a free-form swimming pool, accessible by a broad brick stairway and flanked by two bathhouses that echo the architecture of the house. The pool, considered to be the first free-form pool in California, was designed by Greene to fit within an existing group of live oak trees, many of which are now gone. A wooden cabana, designed by Thomas Church in 19XX, sits at the edge of the south side of the pool deck. A tall wooden fence screens the pool from the driveway on the south and west sides. At the west end of the pool, the fence parts at a viewing platform defined by a low wooden seat wall. From this secluded deck, nicely shaded by oaks, one can look out into the picturesque live oaks on the slope above the driveway.

An old barbecue, built of square cut stones, sits in the lawn that borders the north side of the pool. Complete with copper vent hood, the barbeque is still functional.

Greene’s Folly

Charles Greene also designed a curious little building that was originally used for picnics and family gatherings in the woodland along the creek below the house. Referred to as “Greene’s Folly,” it is a handsome small structure built of knobby fieldstone with a black, glazed-tile, hip roof over a gracefully arcaded façade. Beyond the creek are fields, remnant orchards, and remains of the old Fleishhacker barn. Various pieces of old, rusting farm machinery are left from the days when this area was a functioning farm with cows, pigs, chickens, and vegetable gardens. The area is completely separate from the main house and garden, hidden behind a hill and dense riparian vegetation.

Remnant of an Era

Green Gables is significant today, and for the future, as an example of a country estate that has remained in the same family since its inception nearly one hundred years ago. It appears to first-time visitors as a secret oasis, which somehow has escaped the rush of development in one of the fastest growing regions of California. In this dramatically changing world, we yearn for the opportunity to “step back in time.” We see this in our tendency toward nostalgia and our wish to save old places from destruction. Were it not for the vision and strong convictions of the Fleishhacker family, this property might have been subdivided and developed for “high-end” mini-estates, as have other large country estates on the San Francisco Peninsula and elsewhere throughout the West.

These gardens are remarkable in the attention to design detail, from the larger concept of site and architecture down to the design of plant containers and other artifacts, as well as the selection and placement of trees, all conceived by Charles Greene.

Yet, the estate and its gardens are more than a masterwork of the architect. They reflect the personal desires and needs of the Fleishhacker family. It was built as a refuge for one family who sought to enjoy, privately, the peace and calmness of the setting and to engage in their personal interests—gardening, swimming, and entertaining friends and family. Green Gables is timeless in that it has served three generations of that family, in much the same ways, for over ninety years.

Because of the family’s commitment to the stewardship of Green Gables, the estate—its buildings, gardens, and landscape—has been managed and maintained in impeccable condition for nearly one hundred years. The gardens and landscape appear little changed today, with only a few alterations due primarily to natural causes such as the loss of trees. This has given the estate a timelessness that is uncommon among similar places in California where such estates have been altered, subdivided, or completely lost to unsympathetic owners.

Editor’s Note:

To preserve this magnificent garden, the Fleishhacker family has granted a conservation easement to the Garden Conservancy. This easement prohibits development of the property and protects the historic home and garden created for the family by Charles Greene. As an element of the easement, the property will be open on occasion for special educational tours.

The Garden Conservancy is a national nonprofit organization formed in 1989 to preserve exceptional American gardens for the public’s enjoyment. A new West Coast office is located in the Presidio in San Francisco.

Hadrian’s Villa and the California Garden

Hadrian’s Villa was one of the most monumental and lavish gardens created during the Roman Empire. Located at Tivoli, outside of Rome, its design featured numerous innovations and is a tribute to the talents and vision of Emperor Hadrian. With its rediscovery during the Renaissance, it became an inspiration for artists, garden designers, and architects from the 1400s through the twentieth century.

In March, a two-day garden history and design seminar, produced by The Garden Conservancy and cosponsored by Pacific Horticulture and The Iris & B Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, will explore the legacy that Hadrian’s Villa left to modern garden design, and to the California garden in particular.

Two estates in California—Green Gables in Woodside and Hearst Castle at San Simeon—will be discussed in detail. The seminar will also explore ways in which the Villa’s conceptual ideas and forms can energize and inform the gardens of the present and the future.

The Speakers

Betsy G Fryberger is the Burton and Deedee McMurtry Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Cantor Center. She curated the exhibition The Changing Garden: Four Centuries of European and American Art at the Cantor Center in 2003.

David C Streatfield is a landscape historian whose work has focused on California and the West Coast. A professor at the University of Washington since 1971, he spent the past fall at the university’s Rome Center, directing twenty-four students in a study of Hadrian’s Villa.

Chip Sullivan is a landscape architect on the faculty of the College of Environmental Design at University of California, Berkeley, and has also studied and taught in Rome. He has been working on a series of drawings of experimental gardens that reinterpret traditional garden forms and explore the application of classical and historical landscape elements in contemporary designs.

Eric Weiss, a guide at Hearst Castle, has worked there since 1983. With degrees in history and environmental horticulture, he is involved in the current restoration of the gardens surrounding Hearst Castle.

The Program

David Streatfield will elucidate recent studies on Hadrian’s Villa, stressing the conceptual ideas and fundamental forms of the gardens that influenced artists, garden designers, and architects in the Renaissance, the English Landscape School, and the revival of architectural gardens in the United States in the twentieth century. He will conclude with The Paradox of Hadrian’s Villa and the Arts and Crafts Movement, as illustrated by Green Gables and the California estate garden.

Betsy Fryberger will bring us Ruins Real and Imagined, an illustrated discussion of GB Piranesi, his French contemporaries, and their late eighteenth-century views of the Roman countryside. The artists’ vibrant images romanticized and glorified ancient ruins struggling against the ravages of time and encroaching nature.

Eric Weiss will trace the history of The Gardens at La Cuesta Encantada (Hearst Castle). Just as Hadrian assembled a complex of buildings, pools, and fountains that reminded him of his travels throughout the Roman Empire, Hearst assembled at San Simeon a group of structures that evoked his memories of the Mediterranean. These European influences blend with architectural and garden themes from earlier California country estates and from the Panama-Pacific fairs in San Francisco and San Diego, along with Hispano-Moresque and Italian flavors that make Hearst Castle so unique.

Chip Sullivan will use Hadrian’s Villa to develop A Garden Design Vocabulary for the Future. His analytical diagrams illustrate the unique interpenetration of structure and gardens and the microclimatic effects of solar orientation, wind direction, and psychological dimensions that result in aesthetic and physical comfort. An analysis of the Design and Function of Water Elements at Hadrian’s Villa will highlight the diverse array of aqueducts, grottos, pools, and fountains that tie the complex together and define the unique character of individual spaces. He will propose a set of guidelines on how water might be employed in the contemporary California garden for beauty, climate, and the conservation of energy and resources.

Included in the seminar will be a visit to Green Gables, the seventy-acre property in Woodside that was designed for the Fleishhacker family by Pasadena’s Charles Greene in the early twentieth century. The reflecting pool and grotto at Green Gables are reminiscent of Hadrian’s time but created in a California vernacular. The Fleishhacker family has recently protected this property against future change by a conservation easement held by the Garden Conservancy.

Seminar Details

Where: Stanford University, Iris & B Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts

When: March 5-6, 2005

Fee: $195 (two full days with lunch, including field trip to Green Gables)

Info and Registration: www.gardenconservancy.org; 415/561-3990, fax 415/561-3999; bflack@gardenconservancy.org.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses