Contributor

- Topics: Archive

Much as wasps invented paper long before humans came upon the utility of that now ubiquitous product, other wasps were working as potters and masons before we discovered how to work clay. Many earthen wasp nests are hidden inside stems or far below ground, small and difficult to observe. But potter wasps build their nests in the open, a single, graceful, narrow-necked earthen pot, a mere ½ inch in diameter. Marveling at its fragile perfect miniature form, if you are lucky enough to come across one, it is easy to revert to childhood belief in magical beings.

Female potter wasps build their beautiful pots, often on stems, leaves, or small twigs, as housing for their larvae. Each pot is provisioned with a paralyzed caterpillar, spider, or beetle, and a single laid egg, positioned on the inside of the curved wall above the hapless prey, before the pot is carefully sealed. Potter wasps can be recognized by their curious “double waist’’ an adaptation for bending their abdomen into the inside curve of their pot. Potter wasps’ propensity for capturing caterpillars is an asset in the habitat garden—if only we could teach them to feast exclusively on the cabbage butterfly larvae that attack our brassica crops!

Closely related to potter wasps, mason wasps use mud to build their homes in abandoned beetle tunnels, nail holes, and other handy cavities. Both potters and masons are members of subfamily Eumeninae, a branch of solitary wasps in the Vespidae family.

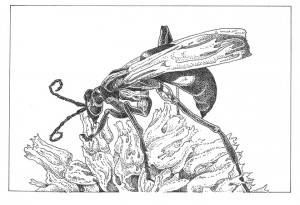

Pompilid wasps (family Pompilidae) are easily observed in the summer garden nectaring on flowers; the adult wasps of the other groups discussed here also nectar on flowers. Solitary spider hunters like some of the larger members of the Sphecid family, Pompilid wasps hunt and paralyze correspondingly large spiders, which they drag into underground nests. They are generally dark-colored, often with a metallic sheen, with amber wings; a few are more brightly hued and can be recognized by their behavior of flitting their wings as they run on the ground looking for prey, (although a few other wasps also share this behavior). Females have gracefully curled antennae.

The tarantula hawk (Pepis thisbe) is one of the largest wasps in the West. Although enormous and reputed to have a powerful sting, like other solitary wasps, Pepsis wasps are generally unaggressive. Years ago, I pointed out to my then-young son a large number of Pepsis wasps visiting angelica flowers in the garden, he drew closer, his nose about six inches from the flowers. How proud I was that day! The wasps went about their business of drinking nectar, and he got a close look at the remarkable metallic blue wasps with the amber wings—an experience he still remembers.

Several other groups of wasps are fairly common in gardens. The Chrysididae, or cuckoo wasps, are generally small, and often extraordinarily beautiful with bright blue or green metallic coloring. The adults feed on flower nectar and parasitize other insects, such as native bees and wasps, by laying their eggs in their victim’s carefully prepared nest where emerging larvae eat the food intended for the victim’s offspring. Cuckoo wasps have relatively small stingers, but as an additional defense, they have a concave abdomen and can roll up into a ball if threatened. While they closely resemble some native bees, they lack the pollen gathering structures that bees possess.

Pollen wasps, the Masarinae, are often treated as a subfamily of Vespidae. Pollen wasps are limited to the arid areas of western U.S. where they build nests of mud or sand attached to rocks or twigs. While all other wasps are carnivorous as larvae, Masarinid wasps are unusual in provisioning their nests with pollen. Most are black and yellow but their unique clubbed antennae easily distinguish them from yellow jackets and other vespids.

Velvet ants—not ants but wasps in the family Mutillidae—are infrequently spotted in gardens but always elicit surprise. The beautiful females, in shades of red, rust, gold, white, and black run over the ground in arid areas of the West; males, though rarely seen, are winged. Both are covered in a dense coat of “velvet,” but don’t be tricked into thinking they can be handled—velvet ants pack a powerful sting. They are known to stridulate or “squeak” when disturbed, should you be foolish enough to disturb one! Not much is known about the life history of velvet ants, but some are parasites of various wasps and bees, and a few attack other insects. Even a short walk around the garden will reveal additional kinds of wasps, each with a fascinating story to tell.

Responses