Contributor

In case you are a bit fuzzy on high school biology, the phylum Arthropoda (joint-footed) shares several notable features: exoskeletons of chitin, segmented bodies, and jointed limbs. The arthropod phylum is further divided into five subphyla—although arthropod relationships are currently undergoing revision based on molecular analyses. One subphylum, Trilobita, is extinct. Chelicerata includes the arachnids, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders; Hexapoda includes the insects and several other six-footed groups; and Crustacea includes roly-polys in addition to crabs, barnacles, brine shrimp, and a few other groups. Finally, there are the Myriapoda (many-footed), which includes the centipedes, millipedes, and symphylans.

In addition to having similar body segments and a single pair of antennae, Myriapods are distinguished by having, as you might expect, myriad legs. They lack the protective calcium-enhanced exoskeleton of the largely aquatic crustaceans, or the waxy cuticle of insects, and require a moist environment to survive. While the Diplopoda (pair-footed) and Chilopoda (lip-footed—more on that in a moment) look superficially similar, they are very different groups; Symphyla (which includes garden centipedes) are in yet another group.

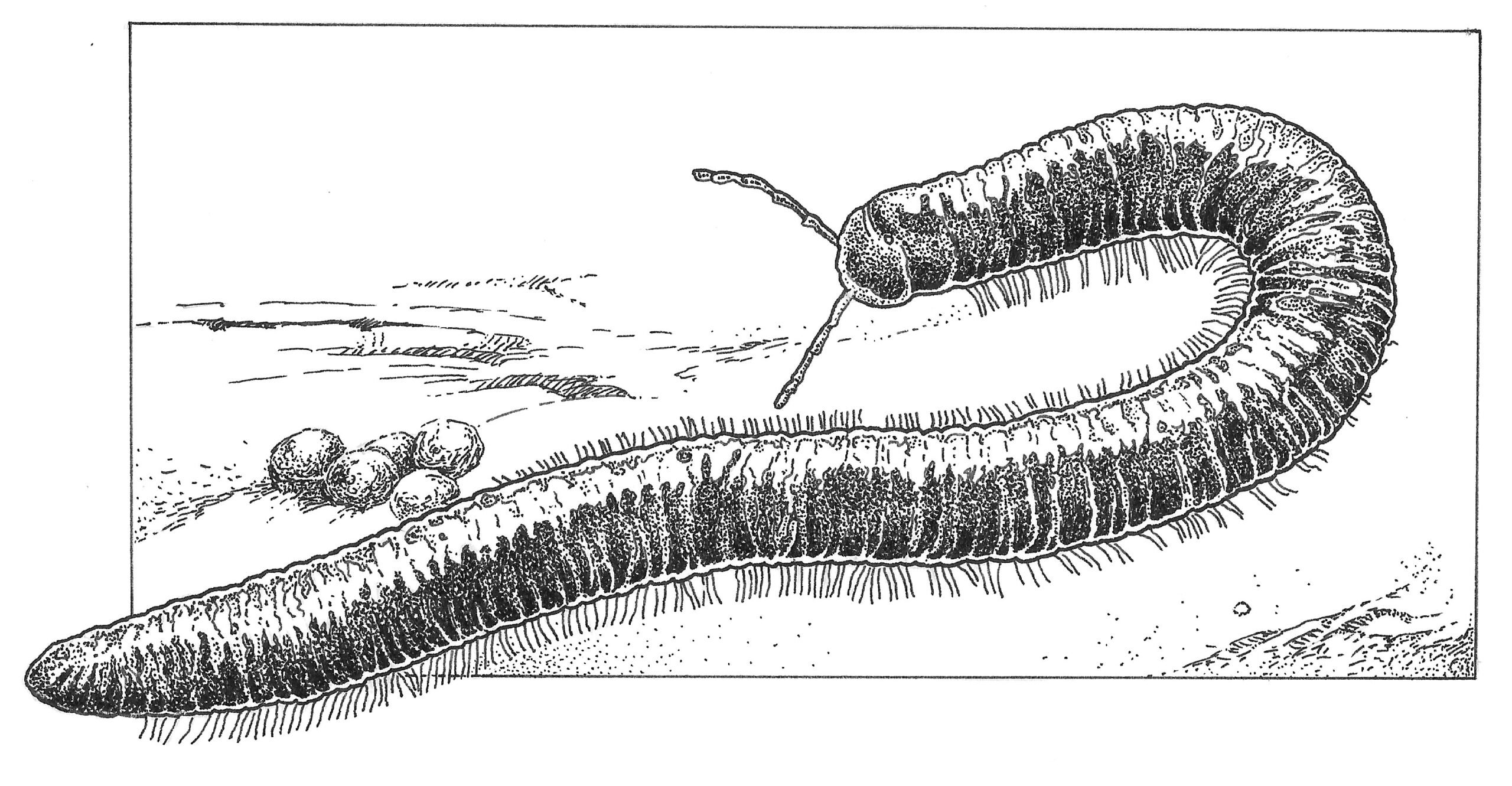

Millipedes (thousand-footed), class Diplopoda, are distinguished by having two pairs of legs per apparent body segment—actually these segments are fused in pairs with one pair of legs each. Most millipedes have long cylindrical bodies with twenty or more segments, and although we call them thousand-footed, generally they have far fewer feet. Still, the distinction of “animal with the most legs in the world” goes to Illacme plenipes, a tiny California millipede that somehow manages to fit up to 750 legs on a less than one-inch body. California is also home to two millipede species that glow in the dark; one is fluorescent, and the other is bioluminescent. For more on this remarkable discovery made in 2013, search “glowing millipedes” on the KQED Science website at ww2.kqed.org.

Out in the garden, you are more likely to spot one of the seven species of the genus Tylobolus found only on the Pacific slope of western North America (with one exception). Tylobolus millipedes are medium to large, and often have faint or sometimes conspicuous yellow or red rings at the back edge of each drab-colored body segment. Millipedes are generally harmless detritivores, eating decaying organic matter, and have an important role in the decomposition of leaf litter. A few species are herbivorous and can be problematic in gardens, greenhouses, and agricultural systems. Slow moving, their primary defense from predators is to coil up. Many species also secrete protective toxins.

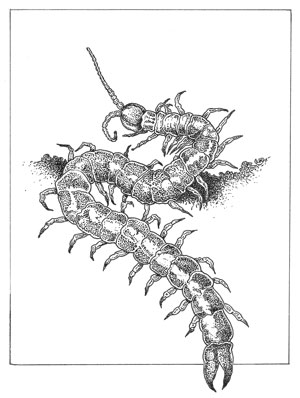

Centipedes (hundred-footed), class Chilopoda, are fairly easy to distinguish from millipedes as they are generally flattened dorsoventrally, that is top-to-bottom. While centipedes only have one pair of legs per segment, they are usually moving so fast it would be difficult to count! What may be easier to spot is that while millipedes have legs of the same length, each succeeding pair of centipede legs is longer than the pair before it. Centipedes range between having 15 and 177 pairs of legs, always an odd number. So there are no centipedes with 100 feet. The front pair of legs is modified into forcipules, the venom injecting claws, or “lip-feet” that are used as accessory mouthparts to capture, paralyze, or kill prey. Centipedes are one of the largest invertebrate predators; some tropical species can reach over 12 inches in length. Thankfully, most species are far smaller.

Centipedes are beneficial in garden environments where they prey on many species of insects, as well as spiders, and other centipedes. Many have subdued coloration, but some, such as the common species Theatops californiensis, are bright orange-red, effectively warning the gardener against picking them up! Like millipedes, centipedes lack the waxy cuticle of insects, and while they may live in an arid environment, are only found where there is moisture—in leaf litter, under rocks, dead logs, and other damp spots.

Class Symphyla, commonly known as garden centipedes, are probably more closely related to millipedes than centipedes. Usually less than one-third inch in length, symphylans have 12 pairs of legs and move rapidly. They are unpigmented and translucent, and live in the soil. Symphylans usually act as detritivores; however, herbivorous species can cause substantial damage in agricultural systems and gardens where they feed on roots and are difficult to control once established. Prevention includes being careful to not incorporate an abundance of organic matter into the soil, especially if it is not fully decomposed. I play it safe by adding compost on top of the soil. Then I let the earthworms and other soil inhabitants do the work!

Responses