Contributor

- Topics: Archive

[sidebar]I am often asked why my insect garden is so full of birds; the answer, of course, is that birds relish insects! [/sidebar]

Butterfly gardens have grown in popularity. Gardeners who once looked askance at including food plants for caterpillars now eagerly seek out information on larval host plants. Butterflies and moths belong to the order Lepidoptera, however, moths remain sadly neglected in the Lepidopteran garden, even though over 95 percent of Lepidoptera species are moths. Gardeners who plan for biodiversity include native plants in their landscapes, and those who refrain from using pesticides invariably develop “moth gardens”—otherwise known as “bird banquet gardens.” Many species of moth larvae are critical bird food, especially in the spring when birds are seeking high-protein, nutritious food for their young.

Although some moth species are among our worst horticultural and agricultural pests, many are well camouflaged—both as adults and as larvae—and damage is often difficult to detect. Birds are essential to controlling populations of many species of moths; however, severe infestations can be a challenge to deal with, and entire communities sometimes find themselves mired in controversy over choosing a solution. The introduction and impact of the LBAM, or light brown apple moth (Epiphyas postvittana) has prompted years of debate even though there is a lack of documented plant damage in the United States. Because the LBAM feasts on dozens of valued plant species, it is feared that the species will reach a tipping point and eventually become a significant problem in the landscape.

The spectacular ceanothus silkmoth (Hyalophora euryalus) is one species whose caterpillars most gardeners would be pleased to encourage in the shrub border. Deceptively named, the species enjoys a broad diet that includes willow, alder, madrone, and other woody plants in addition to ceanothus. One year I led a variety of nature walks at the Fairfield Osborn Preserve in Sonoma County. It seemed that regardless of the topic, our path always passed near a coffeeberry (Frangula californica) festooned with a dozen or so silvery beige cocoons; I called it the entomologist’s Christmas tree. In my own garden, I have planted ceanothus, coffeeberry, mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus), gooseberry (Ribes), and manzanita (Arctostaphylos), all larval host plants for the beautiful ceanothus silkmoth.

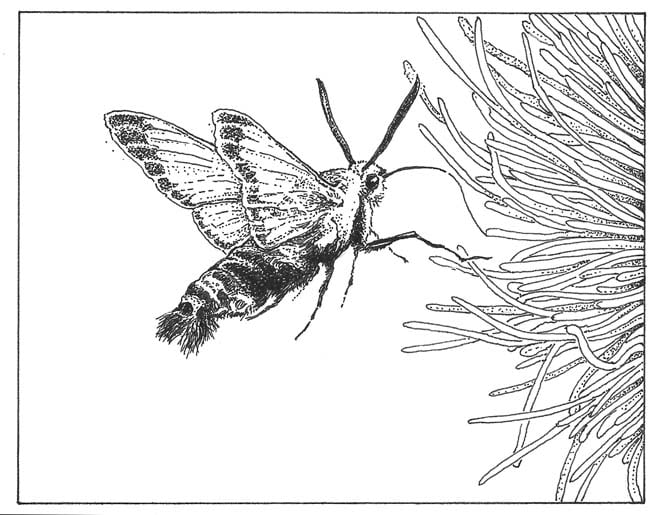

Many moth species have a more narrow range of larval host plants. The artichoke plume moth (Platyptilia carduidactyla), easily recognized by its delicately lobed, fringed wings held in a characteristic “T” shape at rest, feeds on a number of thistle genera including the eponymous artichoke.

Moths are not always easily differentiated from butterflies. Generally, butterflies fly during the day, are stouter in body, and are more brightly colored than moths, with antennae that end in “knobs”—moths’ antennae are usually thread- or feather-like. However, there are also brightly colored, day-flying moths and, surprisingly, some nocturnal butterflies. Several beautiful species of moths can be seen nectaring during the day, and the clear-wing moths, including the aptly named bumblebee moth, and others that mimic wasps (and are known to gardeners as wood-boring pests).

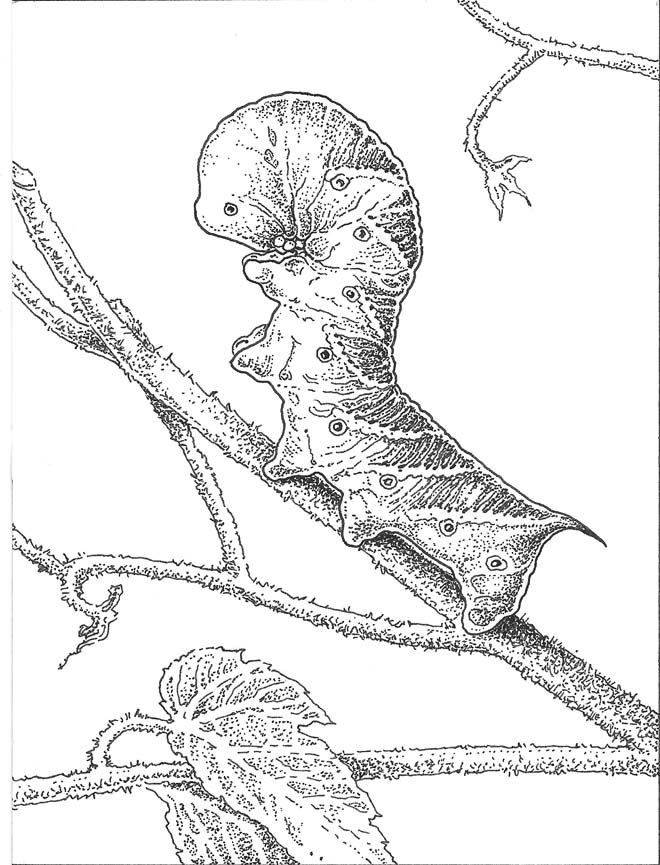

Often, gardeners are more familiar with caterpillars than adult moths. For example, the commonly seen striped “woolly bear” caterpillar is the larva of a tiger moth (family Arctiid). A popular bit of folklore is that the size of the woolly bear’s stripe is an indicator of the severity of the coming winter. The reviled tomato hornworm is the larva of the beautiful sphinx moth (Manduca quinquemaculata), which can be seen at dusk as it visits flowers.

Oak woodlands are thought to host over 5,000 species of insects, including several commonly seen moths. Some years, the California oakworm (Phryganidia californica), is known to completely defoliate the live oaks that are their preferred Quercus hosts. Oaks quickly bounce back from the ravages of the oakworm, leading one moth specialist to suggest the intriguing possibility that since oak leaves break down so slowly, outbreaks of native caterpillars may be fertilizing the oaks, although he is quick to point out that his speculation remains untested (and, thus, he remains unnamed here). Aggregating tent caterpillars (Malacosoma californicum and related species) are easily spotted in their silken tents and, in warmer areas, the fruit-tree leafroller moth (Archips argyrospila) may also defoliate oaks.

Several children I have met in the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden have asked me about Western tussock moths (Orgyia vetusta) dropping from the oak trees on a silken line. I always enjoy relating something I first heard in an entomology course long ago, describing the flightless female adults as “a hairy bag of eggs.” And I watch as their young faces light up with delight at yet another one of nature’s wonders.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Garden Design in Steppe with Transforming Landscapes with Garden Futurist Emmanuel Didier

Summer 2022 Listen to full Garden Futurist: Episode XVII podcast here. Emmanuel Didier, Principal and Creative Director at Didier Design Studio is a leading figure

Seslerias: Versatile Groundcover Meadow Grasses

Summer 2022 Without question, the most beautiful and versatile of all the groundcover meadow grasses are the moor grasses (Sesleria). Moor grasses tick off all

Responses