Contributor

- Topics: Archive

There are those who do not really like insects, but it’s hard to find anyone who does not have a soft spot for lady beetles. Ladybugs, as they are more familiarly known, appear in legends, songs, and children’s stories; they are a popular decorative motif and are beloved by people around the world. Sue Hubbel, author of Broadsides from the Other Orders: A Book of Bugs, dubbed lady beetles “the panda of the insect world.” It is easy to believe that the phrase “cute as a bug” refers to the cheery, polka-dotted beetle. But, while even small children can recognize a typical lady beetle, few of us really know much about this gardener’s good friend.

In Phytologia, published in 1800, Erasmus Darwin, grandfather to Charles, may have been the first to write about the potential for the lady beetle to control aphids. Vedalia beetles, a coccinellid from Australia, were introduced to California citrus orchards in 1888 and were credited with saving the citrus industry, in less than one growing season, from the depredations of cottony cushion scale (a pest accidentally imported from Australia)—thus launching the science of classical biological control, that of using an exotic predator to control a pest (usually also exotic). Other exotic coccinellids, such as the mealybug destroyer, have proved useful in commercial pest management.

The commonly sold convergent lady beetle is a West Coast native. The introduction of a native insect for pest management is known as augmentative pest control, and can also be a successful technique. In the case of the convergent lady beetle, however, garden releases are generally unreliable for pest control, primarily because of the beetle’s natural life cycle. Lady beetles form aggregations in the lower elevations of the Sierra Nevada, where they are commercially collected for sale. Beetles collected from over-wintering aggregations disperse quickly when released into the garden, rarely stopping to feed. Beetles collected from late spring aggregations may not disperse quickly when released but eat relatively few prey. They survive the summer on high fat reserves acquired from eating pollen and nectar in the mountains. Overzealous collection of lady beetle aggregations may be producing a “shadow effect” in parts of the Central Valley, where fewer beetles are returning to their natural habitat. If purchasing lady beetles is of questionable value, and most useful species of lady beetles are unavailable commercially, how can gardeners encourage this useful predator?

To begin with, not all species of lady beetles migrate, and even convergent lady beetles have some year-round populations in milder areas. Lady beetles may form clusters, or aggregations, of anywhere from hundreds to thousands of individuals, and spend the winter sheltered under leaf litter and around the bases of perennial bunch grasses and ground covers. Providing winter habitat in the landscape, and including season-long nectar and pollen sources as alternative food, encourages lady beetles to stay in the garden even when there are no aphids or other pests around.

Good pollen and nectar choices are plants in the umbel family (Apiaceae), such as dill, and the daisy family (Asteraceae). In early spring, I always have thriving populations of lady beetles on the common reseeding annual German chamomile (Matricaria recutita); it seems to function as a virtual lady beetle nursery! I have also found success with Orlaya grandiflora (an attractive annual umbel), Leucanthemum paludosum, perennial fall asters, sunflowers, and cosmos—all suitable insectary plants over a wide geographic area. By providing conditions that attract and maintain native populations of insects, and minimizing or even eliminating the use of pesticides, we are practicing conservation biological control, by far the easiest and least expensive way for gardeners to encourage many species of helpful insects.

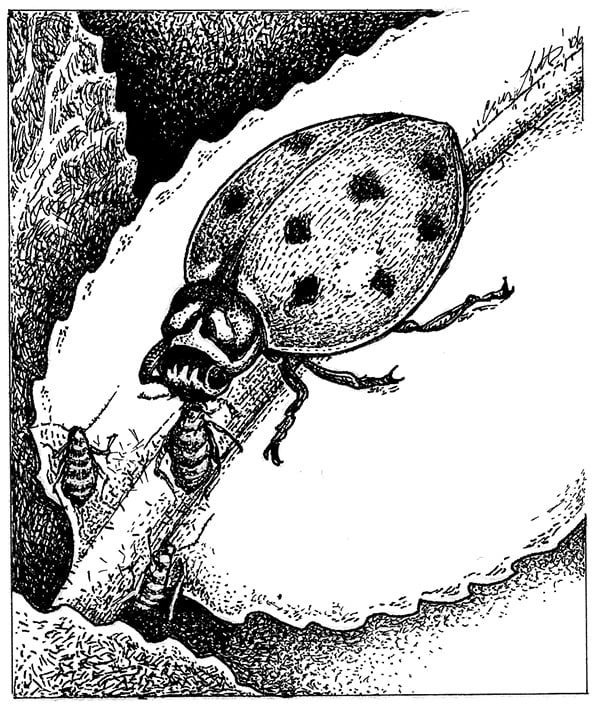

Once enticed to take up residence in the garden, the appetite of the lady beetle is nothing short of amazing, and certainly not lady-like! Many coccinellids are specialist predators, eating only certain other species of insects. Depending on species, a single larva may eat 350 aphids before it pupates; an adult may eat 5,000 aphids in a lifetime. It is fascinating to watch the voracious lady beetles cleaning up a colony of aphids. Scale-eating species can be equally effective, but, since the beetle larvae live under the scales, they are more difficult to detect. Other lady beetles specialize on mealybugs, whitefly, mites, and insect eggs. Some lady beetles eat a more general diet, snacking on a variety of pests.

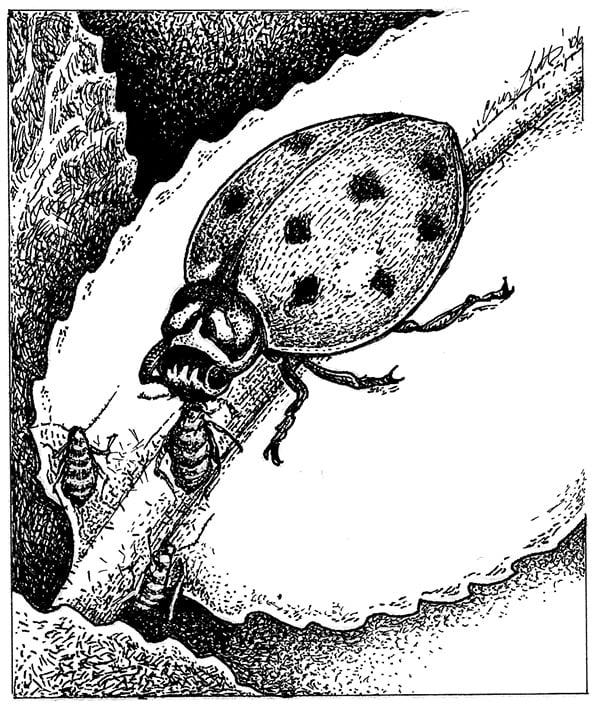

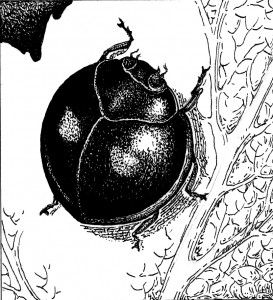

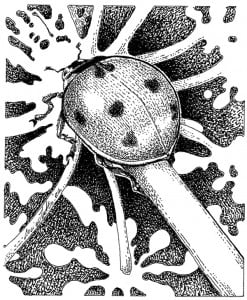

I have not yet identified all the species of lady beetles found in my own garden, but I clearly have many of the common Pacific Coast species in residence. There is the round, dome-shaped, and spotted ‘classic’ ladybug, and of course the more oval and flatter convergent lady beetle. The parenthesis beetle, named for the marks on its thorax, makes frequent appearances. Once a lady beetle has emerged from the pupa, it no longer grows, so the tiny, pale orange lady beetles are not babies, but full-grown members of their species. Perhaps my favorite lady beetle, not often seen, is the twice-stabbed, which has an elegantly shaped dome of shiny black lacquer, splashed with matching red spots. It never fails to make me smile—and perhaps that is the best reason of all to invite lady beetles into the garden.

In a Nutshell

Popular Names:

Ladybugs, lady beetles, ladybird beetles

Scientific Name:

Order: Coleoptera (beetles), Family: Coccinellidae

Common Species:

(some introduced): convergent (Hippodamia convergens), parenthesis (H. parenthesis), two-spotted (Adalia bipunctata), twice-stabbed (Chilicorus kuwanae and three other species), California (Coccinella californica), and seven-spotted (C. septem-punctata). And that’s just the beginning! The spider mite destroyer (Stethorus picipes) is rarely noticed due to its tiny size, the ashy grey lady beetle (Olla v-nigrum) is arboreal, and the Asian multi-colored lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis) comes in a variety of spots and patterns. The list goes on.

Distribution: Over 500 species in North America; about 4,000 species worldwide. Life Cycle: Holometabolous (a complete metamorphosis from egg to larva, pupa, and adult). Appearance:

Eggs: oval and yellow, in clusters on leaves, often near or within aphid colonies. Larvae: like bumpy snub-nosed alligators, often dark with orange spots. Pupae: Rounded, intermediate between larvae and adult in appearance; immobile, attached to a plant or other substrate.

Adults: 1-10 mm (.04-.4”); oval or round, dome-shaped with short, clubbed antennae; front wing covers (elytra) are often various shades of orange or bright red, but may be pale yellow, or black; may have spots or other markings.

Life Span: Typically 4-7 weeks; Asian multi-colored lady beetles may live up to 2-3 years. In mild-winter areas, some species may produce six generations annually.

Diet: Aphids, scales, mites, mealybugs, whiteflies, and insect eggs; generalist species may eat a variety of prey, whereas specialists thrive on only one or a few related species. Adults of many species use pollen and nectar as alternative foods when prey is scarce.

Favorite Plants: Flowers in the daisy and umbel families, shrubs, perennial bunch grasses, and leaf litter.

Benefits: Larvae and adults of most species are voracious predators of numerous kinds of insects and mites.

Problems: Asian multi-colored lady beetles may congregate and move into houses in winter (usually a problem only in cold winter areas). Herbivorous species do not occur on the West Coast.

Interesting facts: Their bright coloration warns predators to leave them alone; if an unwary bird decides to have a taste, lady beetles exude a noxious-tasting fluid from their leg joints. Some species’ larvae have a waxy covering that mimics their prey (mealy bugs) so that they may roam among their victims undetected.

Sources: The convergent lady beetle is the only widely sold species, but many useful garden species can be attracted to gardens with suitable habitat.

More Information:

Natural Enemies, ML Flint & SH Dreistadt, 1998, UC Press. Insects and Gardens, E Grissel, 2001, Timber Press.

Insects of the Pacific Northwest, P Haggard & J Haggard, 2006, Timber Press. Field Guide to Beetles of California, AV Evans & JN Hogue, 2006, UC Press.

Responses