Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Growing for Biodiversity

As I contemplate a magnificent paperweight of a dung beetle rolling its precious ball of manure, a gift from my South African uncle, I am taken back to his last visit and our conversation about this useful insect. Dung beetles are a type of scarab (family Scarabaeidae), and were regarded as sacred by the ancient Egyptians, who perceived in the insects’ efforts a symbol of the sun crossing the sky. Our modern-day appreciation of the dung beetle is more prosaic; because it efficiently rolls up and buries balls of manure (on which it lays its eggs), it has been imported to control flies in rangelands and pastures in California and throughout the southern states.

It may surprise you to learn that over one fifth of all the living species on earth are beetles. In my work, I have often shared a well-known bit of entomological trivia: there are more beetle species than any other animal on earth, and more weevils (family Curculionidae) than any other beetle. Imagine my surprise to learn that there are now more rove beetles (family Staphylinidae)—over 63,000 described species and counting—than weevils. How did this happen? Not only are new species being discovered and described, but some beetle taxa have lost their family status and are now included in the Staphylinidae. Systematists, those who employ modern techniques of genetic analysis in studies of the evolutionary relationships between organisms, have learned more about rove beetles and a certain amount of rearranging has occurred. In the future, this largest of beetle families may be split into four families, once again restoring weevils to highest status. Stay tuned!

Rove beetles are easily recognized. Truncated wing covers leave over half their abdomen exposed with their hind wings neatly folded beneath (yes, they can fly); to the uneducated eye they appear to be an earwig, but note the absence of pincers. A few other beetles share truncated fore wings, but most of those have hind wings untidily peeking out. In a family this large, there is a lot of variation, but most are quite small with bodies that are one-third inch or less, in brown, black, red, or combinations of these colors. Rove beetles are found in just about every habitat provided it is moist. With very few exceptions, they eat just about everything except living plants. Generally, rove beetles are predators of insects and other small invertebrates.

Some species of rove beetles curl their abdomen over their thorax as a threat. The Devil’s Coach Horse (Ocypus olens), an introduced species that can exceed one inch in size, is unmistakable when spotted. Both larvae and adults are fearsome predators; in addition to insects, prey can include earthworms. Ocypus olens has a painful bite, as well as defensive secretions to repel predators. Defensive secretions are common among rove beetles; some members of the genus Paederus produce a highly toxic skin irritant that can result in a painful blister. Having once caught one of these in a slip of folded paper that I slid into my pocket, I was lucky to never learn the location of the escapee.

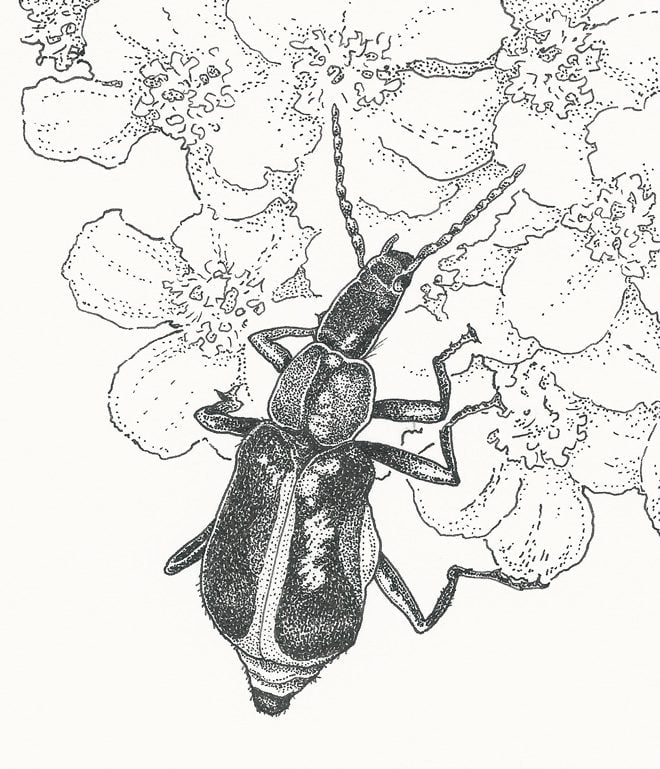

Like the rove beetle, the Cleridae, or checkered beetles, are found around the world with about 500 species native to North America. Most species are predaceous in both the larval and adult stage, preying mostly on other beetles, but some are scavengers and found on carrion in the late stages of decay. Many species can be spotted on flowers, where the adults feed on other insects and on pollen. They are usually much smaller, under an inch in length, but are often conspicuous for their brightly checkered patterns of red, orange, yellow, and sometimes blue coloration. The Ornate Checkered Beetle, Trichodes ornatus, a relatively common species on the West Coast of the U.S., can be spotted on garden flowers. Clerids are renowned for their voracious appetite and for eating other beetles—the larvae most often eat eggs and larvae, while adults prey on adults. Some clerid species found in trees where they burrow into the bark and feast on insects that dwell there may prove to be critical in efforts to control bark beetles. Fewer species are “nest robbers,” feeding on larval bees, wasps and termites.

Another group of beneficial beetles found in gardens around the world are the Soft-winged Flower Beetles (family Melyridae.) These beetles have similar form and coloring, are closely related to—and sometimes mistaken for—clerids. But Soft-winged Flower Beetles are generally smaller; some species can be up to a half inch in length, but most are usually less than a quarter inch. As might be expected from their name, the body has a soft appearance. The predaceous larvae are usually found in soil or leaf litter, or sometimes under bark. Most adults feed on flower visitors and on pollen. In North America, Collops species are a common garden visitor.

With so many beetle species on earth, we have barely scratched the surface of beneficial species to be found. It’s time for another walk around the garden, to see what else remains to be discovered.

Responses