Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Growing for Biodiversity

One day, when I was seven years old, my researcher father returned from doing fieldwork in a bat colony and I discovered a tiny, terrified bat trapped in the car door. I anxiously watched as my dad gently rescued it. Ever since, I have had an affinity for this often-maligned creature and bat stories punctuate my life. There was the time, perched high on a ladder, when I was tearing old sheetrock off a wall and startled a colony of bats as I uncovered their home, or a hot summer night, windows wide open, when a bat careened about our living room catching insects before leaving as suddenly as it entered. I remember an evening drive down a long dirt road watching dozens of bats swoop through our headlights catching their dinner; an auto supply store where a colony of bats improbably emerged at dusk from a sliver of a gap between the wall and a sign; or reading Stella Luna to a small boy, who has grown up to be a man who appreciates bats.

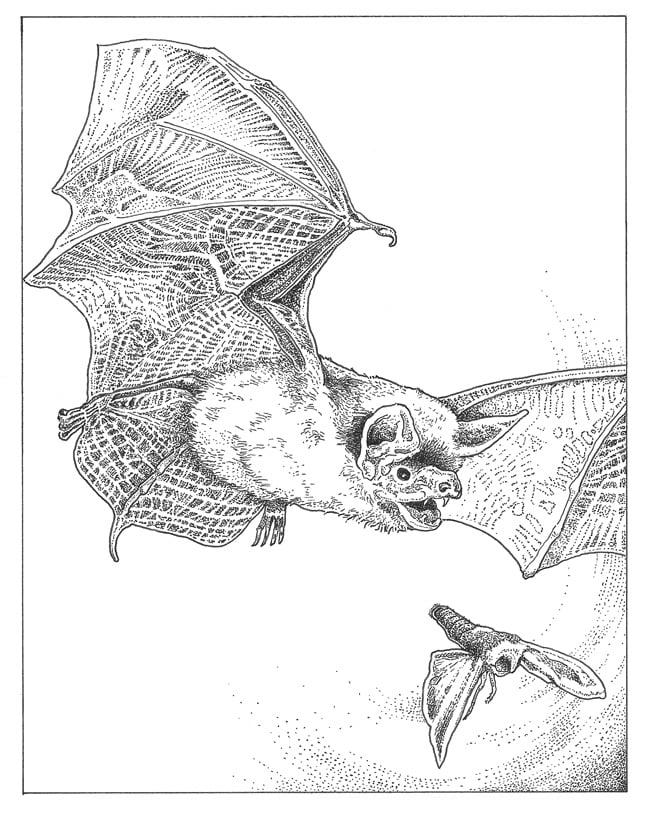

It is always a pleasure to watch bats swoop through the air as they scoop up their insect dinner—a single little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) is reputed to eat over 1,200 mosquitoes in an hour. Insectivorous bats find their prey through a remarkable feature called echolocation; they emit high-frequency squeaks (not discernible to human hearing) that bounce off nearby objects and back to the bat’s ears to pinpoint the location of nearby objects. Incidentally, bats are not “blind as a bat,” but generally possess excellent eyesight. If bats are able to detect objects as small as a mosquito, they aren’t going to fly into your hair, a common fear.

The more than 40 species of bats in the United States are almost exclusively insectivorous, preying on many agricultural pests in addition to mosquitoes; three nectar-feeding species are key pollinators in desert regions. More than 1,200 species of bats are found worldwide, where they play a vital role in most ecosystems. In addition to pest control and pollination, bats are critical to seed dispersal in tropical climates. Despite their ecological value, fear of bats persists and is reflected in language such as “like a bat out of hell,” “batty,” and “bats in the belfry,” and in their association with vampires and rabies. While bats carry rabies, the danger of getting rabies from bats is greatly exaggerated in the media.

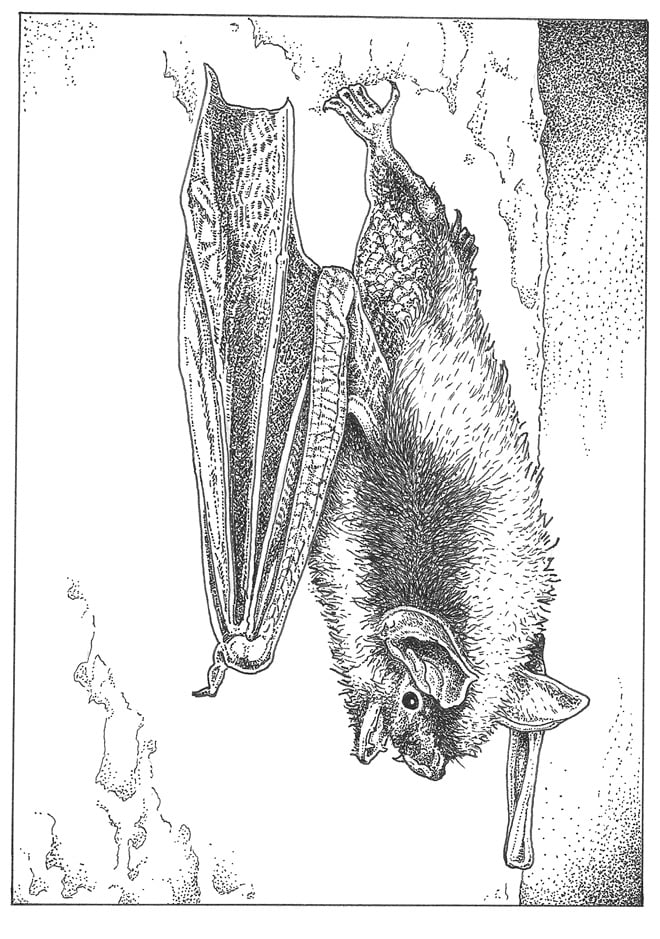

The only true flying mammal, stretch out a bat’s wing and the resemblance to our human hands is instantly apparent. While bats are often thought of as flying mice, or souris volant as the French say, they are not in the order Rodentia but in their own mammalian order, the Chiroptera. Unlike mice and most other rodents, Chiropterans reproduce slowly and may only bear one or two young annually. They also have a long life with an average lifespan of about 20 years; while some species only live a few years, bats have been known to reach 40 years of age. Bats are unique in being the only mammal that is born feet first. Females hang by their thumbs to give birth, forming a “cradle” with their wings to capture the baby.

Several bat species can be spotted in gardens. The western pipistrelle (Parastrellus hesperus), the smallest bat in the United States, is common in desert regions and lowlands, and is often the first bat to be spotted in the evening. The Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), sometimes known as the Austonian bridge bat, named for the famous colony that summers under the Congress Avenue Bridge in Austin, Texas, has been designated a species of special concern—a protective standing assigned by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife given to wildlife species considered at risk.

The common little brown bat and the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) are found throughout the United States and are among the species susceptible to white-nose syndrome, a fungus which has devastated bat colonies in North America during the past decade. Another significant factor in the loss of bats is agricultural pesticide use, which reduces populations of insects on which bats feed, while contaminating insects that have survived the poison. Bats have also been greatly affected by habitat loss due to human activity.

Colonial bat species often have different roosts for giving birth and for overwintering and different species are known to share roosts. The preferred roosts of the bats discussed here include barns and houses. For many reasons, keeping your home free of bats is desirable, but why not put up a bat house and invite these mosquito-dining mammals to take up residence nearby? Most evenings, I enjoy a walk in the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden where one of the many pleasures of my twilight walk is watching the bats emerge as the dusk deepens.

Responses