Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Inspired Gardens and Design

This summer, at Stanford, visitors can see the university’s oldest and newest garden areas, as well as the exhibition, The Changing Garden: Four Centuries of European and American Art, which has recently opened at the Iris & B Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts. The exhibition draws together some 200 prints, drawings, photographs, and paintings by more than one hundred artists. Garden images are presented from three perspectives. The first is an overview of design issues—from terrain, texture, and color, to uses of water, statuary, and architectural embellishments. The second is a selection of influential historic gardens from Villa d’Este, Versailles, and Stowe to urban parks in London, Paris, and New York. The third examines gardens as places to gather (whether for intimate conversations or fashionable promenades), as settings for celebrations or performances, and as subjects for artists.

The New California Garden

The newest Stanford campus garden, which rapidly took shape in October 2002, is near the Cantor Center and its adjacent Rodin Sculpture Garden. Both gardens are located at the corners of Roth Way and Lomita Drive, within a block of Palm Drive. Devoted to California native plants, this project was commissioned in conjunction with the Cantor Center’s exhibition and has been made possible by an anonymous donor. New York-based sculptor Meg Webster designed the garden around a central depression enfolded by two berms, into which she has sculpted two undulating concrete benches. One bench is placed inside the central depression, while the other faces the Rodin Sculpture Garden. In Webster’s words, these benches are for “viewing, rest, and study. They are meant to be objects within the landscape and to draw the viewer to them, giving a sense of place and human scale….I want the viewer to be encircled and held by the earth. The planting of many species of native plants ties the work to the past, to the place, and to Nature.”

Last November, just before December’s heavy rains, Webster planted native shrubs, perennials, grasses, bulbs, and a few annuals in the new garden. She selected them for their texture, color, and beauty, as well as for their educational value to both casual visitors and those wanting more information about native plants. (A partial plant list is available at the Cantor Center Lobby.) The new garden is next to the William M Keck Science Building; its twenty-year-old landscape includes coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) and giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron gigantea), which have received regular irrigation since planting. In the sunnier southern exposure along Roth Way and Lomita Drive are hybrids of coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) and interior live oak (Q. wizlizenii), which receive no supplemental irrigation. In February, two coast redwoods were added to extend the tree zone farther along the building, and another oak was added along Roth Way. A large California mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus betuloides) has been transplanted next to the bench inside the berms to help establish a more human scale among so many smaller plants in the new garden. The garden will need several years of growth before one can fully appreciate the design and plant compositions.

Among the plants Webster chose for moist shady areas near the redwoods are huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum), yerba buena (Satureja douglasii), and leopard lily (Lilium pardalinum). In the sunnier but still damp areas, plantings include California rose (Rosa californica) and California coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica). For the sunny and dry central area of the garden, Webster selected several currants, including hillside currant (Ribes californica var. californica), and such grasses as California fescue (Festuca californica) and purple needle grass (Nassella pulchra). Many of the native species used in the garden are also found on Stanford’s 1,200-acre Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve and in Palo Alto’s Foothill Park, including California mountain mahogany, the small-leafed Ceanothus thyrsiflorus, and the handsome, red-berried toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia).

The Old Arizona Garden

An easy walk from the Cantor Center takes the visitor to the oldest surviving garden on the Stanford campus. Situated near the Mausoleum, it is hidden among the trees to the north of Campus Drive and Lomita Way. Starting in 1876, Leland Stanford purchased some 8,000 acres on the San Francisco Peninsula, creating the Palo Alto Stock Farm. Soon the Stanford family was spending summers away from the chilly fog of San Francisco at their sunny retreat. In 1878, Thomas Hill recorded a family gathering on the lawn in his large painting, Palo Alto Spring, on view at the Cantor Center. The Stanfords had intended to build a larger country house and to expand the plantings.

Among the new attractions installed in the early 1880s was the Arizona Garden of cactus, succulents, and tropical plants. Designed by Rudolph Ulrich, the plants came from Arizona and Mexico, where he had collected specimens from the Sonoran Desert. Ulrich had earlier created similar gardens (each typically called an “Arizona Garden”) for Milton Latham’s Thurlow Lodge (now the site of Menlo Park’s city center) and for the Hotel del Monte in Monterey, which has recently been restored. An early photograph of the Monterey garden shows specimens of saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) towering over admiring visitors. In the Stanford and Monterey gardens, saguaros, yuccas, aloes, prickly pears (Opuntia spp.), palms, and herbaceous plants were elaborately arranged in circular and scalloped beds according to the prevailing Victorian taste.

Early University Plans and Plantings

After the death of young Leland Stanford Jr in 1884, the grieving parents abandoned plans for their new house. Instead, they turned their attention to erecting a suitable memorial to their son and settled on founding a university. Their extraordinary financial commitment (estimated to have been about twenty million dollars), coupled with the extensive lands they donated, was virtually without precedent in the history of American colleges and universities. John D Rockefeller made an equivalent or larger financial commitment about the same time to found the University of Chicago, but its grounds were far smaller. The two campuses could hardly have been more different in plan or plantings. The Chicago campus was urban in character, built on flat terrain and landscaped with trees and lawn; its quadrangles followed the English university plan. Stanford’s open grasslands, which rose to small hills dotted with oaks, called for a more open configuration with plantings appropriate for California’s hot, dry summers.

In 1886, Stanford turned to landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who, in 1860, had presented a park-like design (never built) for the College of California at Berkeley (today the University of California). Olmsted had designed several Eastern college campuses in the English naturalistic style and envisioned an informal grouping of campus buildings with a botanical garden of California natives. Stanford, however, had toured the capitals of Europe and favored a monumental and symmetrical campus design. From their difficult collaboration came the final plan of 1888, which showed the main axis of Palm Drive and the enclosed, arcaded quadrangle dominated by Memorial Church. Within the central quad, Olmsted designed eight landscaped islands with drought resistant plantings, much of which survive today. The silhouettes of the islands are dominated by palms, especially Mexican fan palm (Washingtonia robusta), Chinese fan palm (Livistona chinensis), and Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis). Recently, these dramatic specimens have been underplanted with a variety of compatible shrubs and ground covers.

Given the financial problems faced by the young university, it is not surprising that the Arizona Garden and other early landscape projects received little subsequent attention. Some specimens were probably relocated, including a century-old Yucca filifera, long hidden among smaller oaks at the northern end of the Cantor Center (originally the memorial Leland Stanford Jr Museum). That imposing survivor has recently been joined by Mark di Suvero’s dynamic red steel sculpture, The Sieve of Eratosthenes. For most of the twentieth century, however, the Arizona Garden was known as a mysterious, overgrown area, sought out mainly by students for nocturnal visits. Its surviving yuccas, more horizontal than vertical, now recline as the result of too much winter rain.

Stanford initiated an ambitious program to develop a portion of the campus as an Arboretum, intended as a comprehensive collection of trees and plants of temperate climates. This greenbelt area, which covers more than one hundred acres and separates the campus from Palo Alto, was once crossed by diagonal paths planted with many cedars and other tender trees now gone. Several species of Eucalyptus were initially planted as nurse trees to protect the young specimens. Early in the twentieth century, however, the care of the Arboretum was curtailed, with the consequence that the less vigorous trees died and the eucalypts thrived. Many of the century-old eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus, E. camaldulensis, E. viminalis) still survive, but are in declining health.

Recent Plantings and Projects

Within the last five years, using documents in the University Archives and with the help of campus archeologist Laura Jones, Julie Cain and Christy Smith have coordinated a volunteer effort to rebuild the old Arizona Garden’s beds, with their serpentinite edgings, and to add appropriate plantings. In a forthcoming article to be published by the Stanford Historical Society, Cain cites several of the more unusual new plantings: tree aloes (Aloe dichotoma), the spiral-shaped A. polyphylla, and the curious boojum tree (Fouquieria columnaris).

An encyclopedia of nearly all the tree species found on campus is a major project reaching completion and will also be published by the Stanford Historical Society. Its author, Ronald Bracewell, professor emeritus of electrical engineering, brought with him from Australia a keen interest in Eucalyptus. The book will include six tree walks, including one near the Cantor Center and another in the Main Quad.

Many oaks, toyons, and manzanitas (Arctostaphylos) now line campus streets and paths, ring the Arboretum, and cluster in small welcoming groves around newly placed benches. On the main campus and in the hills above, thousands of acorns have been planted over the past decade by Magic Inc, a local non-profit organization dedicated to reforestation. Some of the young oaks are now reaching four feet in height.

Native species and those from other regions of mediterranean climate can be found in the garden area behind the new Arrillaga Alumni Center on Galvez Street at Campus Drive. Elsewhere on campus, Peter Walker’s designs for the Schwab Residential Learning Center include a courtyard with a stunning array of palms. All of these projects have been developed with the advocacy and support of Stanford University architect David Neuman and manager of grounds Herbert Fong.

Garden Exhibition and Walking Tours

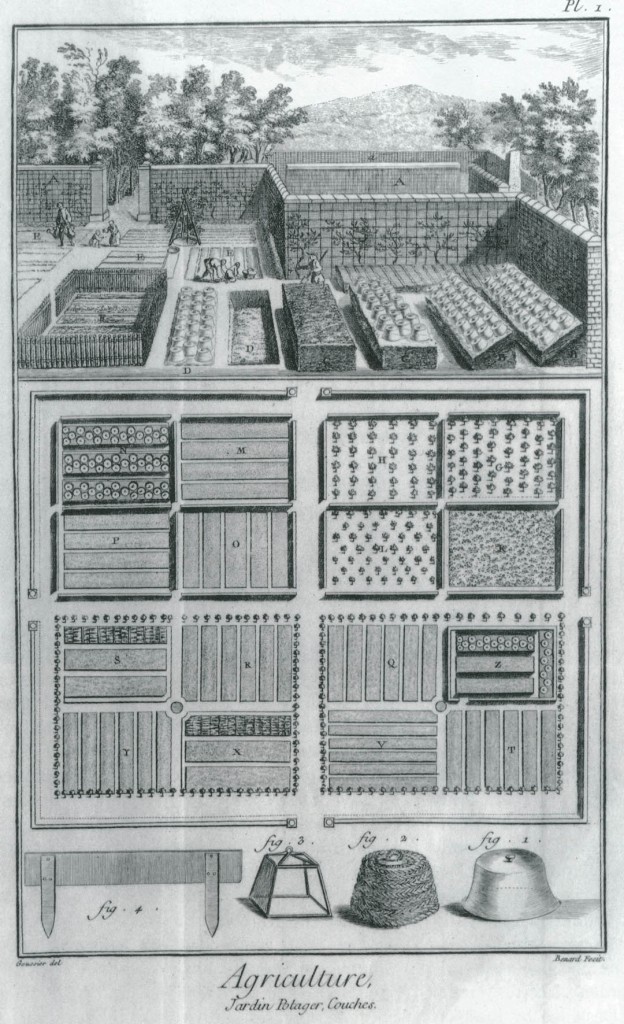

Until September 10 at the Cantor Center, a wide selection of garden representations can be enjoyed in the exhibition, The Changing Garden: Four Centuries of European and American Art. Sixteenth-century images include Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s engraving of the flurry of pruning, planting, and other spring activities. Both the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, and Versailles are shown in groupings of views across four centuries, from prints made as the gardens were being built to photographs of their recent appearance. Among late nineteenth-century photographs are several of Arizona gardens—on the Stanford campus, the Hotel del Monte in Monterey, and Carleton Watkins’s view of Latham’s Menlo Park estate. The twentieth century is represented by, among others, John Singer Sargent, who sought out many European gardens and celebrated them with bravura in his paintings and watercolors. Other American painters portrayed crowds enjoying New York’s Central Park. Photographs by Eugène Atget record aspects of Versailles in about 1900. Michael Kenna, Marion Brenner, and Laura Volkerding offer their recent photographic interpretations. At The Huntington in San Marino, California, Volkerding photographed visitors who were busy taking photographs to preserve their pleasant memories of the grand gardens there.

Docent tours of the Cantor Center exhibition are available, as is a tour of nearby outdoor sculpture, including Andy Goldsworthy’s Stone River (constructed from various stone remains of the 1906 earthquake) and the Rodin Sculpture Garden. Other campus walks could begin at the Arizona Garden, continue with the historic trees around the Cantor Center and Rodin Sculpture Garden, and conclude in Meg Webster’s new California garden. (For further information, consult the university’s websites for the Cantor Center, the Arizona Garden, the Historical Society, and Jasper Ridge.)

In preparing this article, I have consulted with many who have generously provided detailed or specialized information. Among these are Karen Bartholomew, Julie Cain, Betsy Clebsch, Herb Fong, and Christy Smith.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses