Checkermallow Love—for Beauty, Conservation, and Pollinators

Contributor

- Topics: Nature is Good For You

Summer 2024

The Blossom and the Bee

It was a brisk early morning in May when I met an insect in love with a plant. High on the west flank of Skinner’s Butte in Eugene, Oregon, I crouched to take a closer look. Curled around a stamen tube in the center of shell-pink petals lay a lightly furred bee. Extending my outsized finger into this little world to touch, I wondered if the bee was dead and why it was there. With antennae draped back like shy dog’s ears, the bee remained still—no reaction to my prodding.

At the time, I was volunteering for the nascent Oregon Bee Atlas, collecting native bees for identification in service of scientific understanding about pollinator diversity. I plucked the hollow flower stem cleanly between thumb and forefinger, and cradled the delicate treasure in my palm as I descended the steep stairs alongside the butte’s columnar basalt wall to return directly home.

After taking a photo of my find, I gasped as I saw small movement, saw life re-awaken from what I presumed to be the finality of death. Under my gaze, in the warmth of my hand, the bee vibrated and stretched its abdomen in a gesture familiar to all waking creatures. Mesmerized, I chose not to interfere as my little friend flew away into the brightening of the day.

It wasn’t until later, talking with Oregon Bee Atlas colleagues, that I learned this is a common behavior of many solitary male bees. While the females provision ground or hollow stem nests with pollen for their brood, males are left on their own to find shelter through the chill of the night. Without a nest, they often bed down within the same flowers they foraged on during the day.

Still fresh, the flowering stalk remained in the cup of my palm. Released now from the wakened bee, I allowed a lingering sense of wonder to rest upon the details of the blooms. Each petal was nearly transparent with striated veins of white. A central tube terminated in a brush of pollen. The pattern looked familiar—like a tropical hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis) in miniature, or a cottage garden hollyhock (Alcea rosea).

The flower in my hand was in fact a rose checkermallow (Sidalcea malviflora ssp. virgata, with the botanical synonyms of Sidalcea virgata and Sidalcea asprella ssp. virgata). This flower is part of the mallow family (Malvaceae), along with hollyhock and tropical hibiscus. Their signature is a pattern of five petals surrounding a column of fused stamen topped with a bottle brush display of pollen-bearing anthers. However, while hollyhock and hibiscus are widely known, even to many non-gardeners, the beauty of checkermallow remains unsung.

This spring bloomer is a delightful gem for dry and wet locations

Living, gardening, and hiking in western Oregon, I was bound to meet up with this wildflower sooner or later. Rose checkermallow has a range that extends through the Willamette Valley and southward to the California border. It took a sleeping bee to draw me in and I haven’t stopped looking since.

You’ll find rose checkermallow on dry, open ground—like where I encountered it on the west side of Skinner’s Butte—as well as in lower, winter-wet meadows. Arrayed in a rosette emerging from deep-diving roots, its leaves are rounded, palmately-lobed, of handsome shape and sheen. There’s nothing that would make you think “weed” about this wildflower’s foliage. In fact, the leaves are as intriguing as the taper-pointed buds and pretty blooms. As they ascend the straight stalks, the leaves become more finely cut, transforming lobes into lace.

Look more closely, down on your knees, and you’ll see a distinguishing characteristic of this species: long strands of soft hair at the base of the stems become shorter and patterned like a star as they march up the stalk. The blossoms, lighting up from spring into early summer months, range from glowing magenta to pale pink, or even white.

Curiously, many Sidalcea species, including rose checkermallow, present some plants with one-inch flowers and others half as wide. The larger blooms are hermaphroditic with both pollen-bearing and seed-producing potential. The smaller flowers are female, without pollen. This unusual pattern of hermaphroditic and female plants coexisting is called gynodioecy. See if you can find both next time you’re hiking in their midst.

Even more curious is the research showing that seed-eating native weevils prefer dining on hermaphroditic plants, leaving the female-flowered plants to persist within a population, rather than evolving toward complete hermaphroditism.

One of the most garden-worthy plants of the Sidalcea genus

Rose checkermallow integrates into any style—modern, naturalistic, cottage, food forest, or even formal parterre. I’d argue that it’s the handsome evergreen leaves that nominate this plant to such worthiness across genres, even more than the pretty pink flowers.

If you look anywhere online, you’ll read that Sidalcea are winter deciduous. I ran into this statement over and over again one wintry day while researching. I was so bothered by how incongruous this information was with my memory of the plant—fresh rosettes in the winter next to blonde grasses—that I had to leave the computer, put on my old Lems boots, and trek up Skinner’s Butte again to confirm my memories. Yes! There it was, in January, looking absolutely smashing in green.

I shared this little story of incongruity and misinformation about checkermallow’s evergreenery on Instagram and was flooded with fellow Oregon gardeners saying, “They’re always evergreen for me,” and “I’ve noticed that too in my own yard!” and “Sure is around here!” My client Erica even said she thinks winter is their best time of year in her garden.

Rose checkermallow supports a diversity of pollinators

If the dapper foliage doesn’t convince you, then let me tell you about her pollinator friends. She’s quite popular! Rose checkermallow is a big deal for Pacific Northwest butterflies. She’s is a host plant for gray hairstreak (Strymon melinus) and checkered skipper (Burnsius communis) butterflies. She provides nectar for Taylor’s checkerspot (Euphydryas editha taylori) and for the nationally endangered Fender’s blue butterfly (Icaria icarioides fenderi). While I can find no reference that confirms the origin of the name checkermallow, I think it’s a safe bet that the checker-patterned butterflies that accompany Sidalcea, along with the mallow family identity, are responsible for today’s alias.

If bees fascinate you, then consider that rose checkermallow is included in Oregon State University’s peer-reviewed report on the top ten native plants for wild bees—all the gold stars for this blooming beauty (Anderson et al. 2022). Her list of native bee celebrities includes the specialist black-fronted turret bee (Diadasia nigrifrons). Specialist bees rely on a single plant species, making them particularly vulnerable when their host plant declines. Cuckoo bees (Nomada sp.) and Edwards’s long-horned bee (Eucera edwardsii) are also known checkermallow associates.

When you add rose checkermallow to your garden, you’ll see firsthand how native pollinators (not just honey bees) flock to the native flowers. In addition to the butterflies and bees, hummingbirds, beneficial insects, and even seed-eating birds are known to dine on the bounty of rose checkermallow. All these colors and patterns of wings could enliven your garden when you plant to create habitat.

Checkermallows in the wild are at risk

The genus Sidalcea is a distinctly western clade. OregonFlora lists 13 species and many subspecies. Calflora lists 24 species native to California. There are a few pocket populations in Washington and two species known from Mexico. There are no Eastern North American, European, or Asian checkermallow species. Perhaps that’s why it’s little known—garden plants inherited from the Old World have dominated horticulture.

Quietly, for centuries, checkermallows flourished throughout the Pacific region alongside grasses, geophytes, dam-building beavers, and the Indigenous peoples who tended the land with fire. These are plants, like many from the West, that thrive in a reciprocal relationship with people.

In Charles Wilkes’s narrative of the US Exploring Expedition of 1841, he described the Willamette Valley as it must have appeared for the thousands of years of the Kalapuya peoples’ residency: “The prairies are at least one-third greater in extent than the forest: they were again seen carpeted with the most luxuriant growth of flowers, of the richest tints of red, yellow, and blue, extending in places a distance of fifteen to twenty miles” (Wilkes 1845).

These historic wildflower carpets succumbed to the plow and the grazing pressure of livestock as colonists moved in. Persisting now in roadside ditches, many natural populations of checkermallow are at risk from roadside spraying programs.

Sadly, the small community of rose checkermallow in Washington is in danger of extinction. Without cultural fire on wildlands, conifers and invasive species like Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) shade out sun-loving wildflowers.

As a plant of conservation concern, growing checkermallows in your garden is a meaningful act of contribution towards something better. I know of one thoughtful gardener on the edge of town who cultivates various species of Sidalcea as “mother colonies.” She envisions them seeding into the wild meadows beyond her property.

This remarkable evergreen perennial is easy to grow

Adapted to the heavy, winter-wet, summer-dry clay of the Willamette Valley, rose checkermallow is easy to grow here. Unlike their relatives, hollyhocks, checkermallows are rust resistant with healthy foliage and flowers—and they’re edible!

The two-foot-tall spires of pink flowers are a pretty addition to your sunny or lightly shaded plantings. Watch them wave in the spring breeze alongside native companions like Oregon iris (Iris tenax), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), and bigleaf lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). Equally, checkermallows compliment classic perennials like penstemons (Penstemon spp. and cvs.) and peonies (Paeonia spp. and cvs.). Think of them when deciding how to fill the ebb in color following early spring bulbs and before peak summer blooms.

You can pamper them with compost and irrigation in your flower garden for a repeat bloom or leave them to the vagaries of summer drought as they are in the wild. Not all native plants are so adaptable to garden culture. I’ve killed some promising young Columbia tiger lilies (Lilium columbianum) with my overly nurturing attention.

Include checkermallow in your disconnected downspout rain garden. Conditions along these margins are similar to the beaver-modified landscape that previously fed our local wetland biodiversity. If you have a wet spot in your yard, don’t drain it. Celebrate it as an opportunity to grow checkermallows and other plants adapted to saturated winter soils.

As you go about your garden puttering, plucking a weed here and trimming an overhanging limb there, you replicate the competition-reducing benefits of cultural fire. Trim spent flower stalks down, leaving 12 to 15 inches standing for nesting bees. Nothing more is needed to steward this plant. Rose checkermallow is a wonderful gateway perennial that will open the door to the joy of growing natives, and in my opinion is the most eye-catching perennial native to western Oregon.

Garden Futurist Podcast: Episode XXXIV: Protecting Invertebrates from Pesticides with Aaron Anderson

Invertebrates do so many important things. But beyond the benefits they provide to ecosystems, they’re fascinating creatures. When you look at them closely, bees are all sorts of metallic colors. There is a beautiful diversity of butterflies. Parasitoid wasps have amazing antenna that are branching in different directions. A lot of us just aren’t aware of them when we’re out in a garden or going for a walk, because so many of them are so small. The more people appreciate how cool they are and how important they are, hopefully the more interested they’ll be in conserving them and protecting them. >> Listen

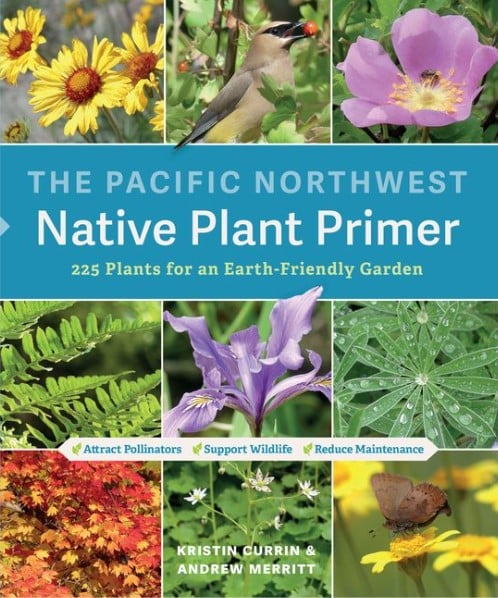

Book Review: The Pacific Northwest Native Plant Primer by: Leslie Davis

Kristin Currin and Andrew Merritt’s new book about gardening with native plants is a call to action, a guide, and, importantly, a reminder of the childlike pleasure of observing flowers, insects, and birds, of connecting to nature where you live. Planting natives is rightly getting a lot of attention lately in the face of species decline. This book’s introduction roots the impulse in joy and hope rather than fear.

Other Species and Cultivars

Explore more of the Sidalcea universe. Consider other species of checkermallow available from your local native plant nurseries. Here’s a few great garden choices that I’ve found from Oregon growers.

Meadow checkermallow (Sidalcea campestris) has white to pale-blush wands nearing six feet tall—usually closer to four feet tall. As an airy scrim of white dotted throughout a perennial bed, she compliments any planting theme.

Image: Meadow checkermallow (Sidalcea campestris) has white to pale-blush wands nearing six feet tall—usually closer to four feet tall. As an airy scrim of white dotted throughout a perennial bed, she compliments any planting theme.

Cusick’s checkermallow (Sidalcea cusickii), the perfect hollyhock substitute, rises the tallest with super cottagey, clustered flowers of bright pink turning to deep purple as they fade. This is a species that’s rare and threatened in its western Oregon wetland habitat, limited to Lane and Douglas counties. Growing Cusick’s checkermallow from responsible nursery sources contributes positively to its conservation. Tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa) is a natural companion in the wild—a beautiful combination worth imitating.

Image: Cusick’s checkermallow towers alongside Sunstruck rose (Rosa ‘Sunstruck’) in the Open Air Living Room Garden. Credit: Leslie Davis

Henderson’s checkermallow (Sidalcea hendersonii) is a coastal species that is found from southwest British Columbia south to the mouth of the Umpqua River. Growing to just under three feet tall, this checkermallow is best in compost-amended beds with regular summer irrigation. Plant some with your roses and delphiniums.

Even though the West is the heartland of Sidalcea species, they did manage to capture the attention of the early 1900s British plant collector Reginald Farrer. Checkermallows then traveled to the horticultural breeding grounds of the Old World, ready to make a break on the herbaceous border scene. The resulting cultivars include:

Sidalcea ‘Elsie Heugh’ was bred to favor larger blooms, two inches across, growing to the friendly height of 2–2.5 feet tall. She’s the recipient of the prestigious Award of Garden Merit form the Royal Horticultural Society.

Sidalcea ‘Little Princess’ is a relatively recent (1994) introduction out of Hummelo in the Netherlands. Aad Geerlings crossed two unidentified seedling selections of Oregon checkermallow (Sidalcea oregana) to get this cutie that stands at 1.5–2 feet tall.

Sidalcea ‘Party Girl’ is pink, full of blooms, and potentially the tallest of this group at three feet.

Continue to Pay Attention

This deep dive into the world of checkermallows started with that chilled morning walk when a small creature’s sleep drew me in.

The author Daisy Hildyard (2022) wrote, “A person might understand her position in the world not by introspection but by looking out and paying attention to the agency of other beings, even when this view diminishes or displaces her right to priority.”

I would add that paying attention also allows you to see your role in the interdependence of all things. As a gardener, you have a real opportunity to learn from nature and make a positive contribution. It can be as simple as planting a few checkermallows.

This article was sponsored by:

Resources

Anderson, Aaron, LeAnn Locher, Jen Hayes, Mallory Mead, Signe Danler, Diane Jones, and Gail Langellotto. 2022. Native Plant Picks for Bees: 10 Species You Can Grow to Support Wild Bees in Oregon. EM 9363.

Currin, Kristin and Andrew Merritt. 2023. The Pacific Northwest Native Plant Primer: 255 Plants for an Earth-Friendly Garden. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Gisler, Melanie Marshall, and Rhoda M. Love. 2005. Henderson’s checkermallow: The natural, botanical, and conservation history of a rare estuarine species. Kalmiopsis 12. [pdf]

Haskin, Leslie L. 1934. Wild Flowers of the Pacific Coast. Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort.

Hildyard, Daisy. 2022. “War on the Air: Ecologies of Disaster.” Emergence Magazine. June 27, 2022.

Kruckeberg, Arthur and Linda Chalker-Scott. 2019. Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest. 3rd ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Pojar, Jim and Andrew MacKinnon. 1994. Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia, & Alaska. Tukwila, WA: Lone Pine Publishing.

Wilkes, Charles. 1845. Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard.

Responses