Contributor

- Topics: Archive

[sidebar]For information about the series of events and exhibitions commemorating the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, including a special “garden weekend” May 9-10, visit www.balboapark.org.[/sidebar]

One hundred years ago, the Panama-California Exposition—a Spanish Colonial Revival fantasyland—was built in Balboa Park. The exposition was a daring attempt to thrust San Diego, a small city of fewer than 40,000 people, into the national and international spotlight. No one could have predicted how profoundly the decision to build an exposition on park grounds would affect the future of Balboa Park, or the influence it would have on landscaping norms throughout Southern California.

City Park Early Days

San Diego appeared visionary in 1868 when it created an urban park larger than Central Park in New York City. However, absent a design or maintenance plan, the 1,400-acre site remained an unimproved expanse of natural coastal chaparral that included a dumping ground and shooting range. Other non-park activities—storing explosives, impounding stray animals, and an outdoor abattoir—gave rise to place names like Powder House Canyon, Pound Canyon, and Slaughterhouse Canyon. People with communicable diseases were quarantined in a park “pest house.” Dismayed by dim prospects for enhancement, some locals advocated a reduction in park size, and real estate investors circled greedily, awaiting the removal of park land from public ownership.

The City of San Diego claimed that it had no money for improvements but was willing to approve private initiatives. However, throughout the 1880s and 90s citizen actions to improve City Park proved transitory as drought, vandalism, unauthorized grazing, and financial reversals took their toll. The far southeast corner of the park fared best with sustained grassroots improvements made by the wealthy neighborhood of Golden Hill.

As private efforts to improve the park failed and official civic disinterest continued, pressures to sell off parkland mounted. Unable to force the City Council to act, the Chamber of Commerce created its own Park Improvement Committee in 1902 and hired Samuel B. Parsons, Jr., to create a comprehensive plan to protect and preserve the park for public use.

Parson’s plan

A national leader in his field, Parsons was the landscape architect of greater New York, had previously served as Superintendent of Central Park, and was President of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Parsons visited San Diego’s City Park in 1902 and, in the planning tradition of English landscape gardeners, “consulted the genius of the place.” Describing San Diego’s park as beautiful and unique in the world, Parsons recommended preserving the views of mountains and sea. His final plan proposed restrained planting using species appropriate to San Diego’s climatic realities. Mesas should be largely unadorned, he wrote, with denser planting defining park entrances and highlighting the park’s dramatic canyons. Public buildings in the park were to be discouraged, but if absolutely necessary, they should be kept to the southern end of the park. Likewise, Parsons suggested that any formal gardens of seasonal flowers be located in the same area, near to the downtown.

Parson’s plan for City Park was to “preserve and accentuate natural beauties of a very unusual kind, which we trust may be kept free from interjection of all foreign extraneous and harmful purposes or objects.” Do not bring the city into the park, he warned, maintain it as an alternative to city life.

The plan was quickly implemented under the direction of George Cooke, Parson’s landscape business partner. Pleased with the progress, in 1905 San Diegans voted to create a fund for park development and the first Board of Park Commissioners was appointed. City Park was at last under civic management and being improved.

However, just as Parson’s plans were beginning to be realized, the 1915 exposition was proposed—an exposition that would occupy City Park and proceed without regard for the core principles underlying the vision of Samuel Parsons. Something of a salvation for the park only a few years earlier, the Parsons plan now became a victim of exposition fever. The newly established Panama-California Exposition Corporation pushed for a more prepossessing name for its exposition site and in 1910, City Park was renamed Balboa Park. Resolved to bring in the best talent that money could buy, the exposition’s Building and Grounds Committee hired The Olmsted Brothers, an eminent landscape architecture firm experienced in exposition design.

Olmsted’s plan

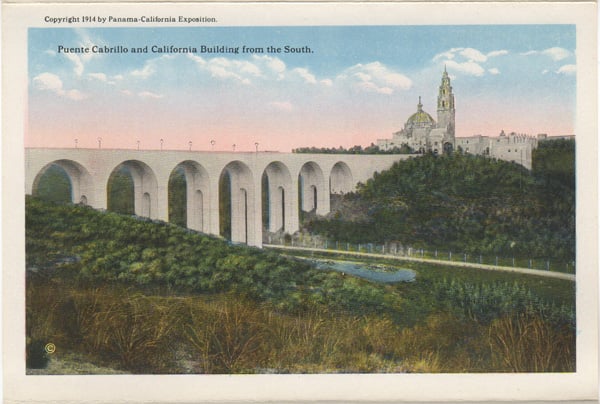

By December 1910, John Charles Olmsted began work in San Diego. He quickly completed early plans for the Panama-California Exposition and a framework for other roads and landscaping in Balboa Park. Olmsted suggested using plants appropriate for San Diego’s Mediterranean climate and avoiding big green lawns. An exposition nursery was established to propagate the thousands of plants that would be needed including several notoriously difficult native species. Hardscape, like the gardens of Italy and Spain, would be artfully deployed in bridges, walls, and covered walkways.

After looking over all of Balboa Park, Olmsted chose an exposition site at the south edge, conveniently located near downtown San Diego. This choice of location reflected an urban park planning philosophy in accord with that of Parsons: city parks should be preserved as oases of nature and quiet retreats from urban life. Buildings, if necessary, should be restricted to the perimeter.

The ink on Olmsted’s exposition design was barely dry when efforts to undermine it began. The powerful personages of Frank P. Allen, Jr., and Bertram Goodhue did not like Olmsted’s choice of location. As Director of Works, Allen was charged with getting all buildings and grounds ready for opening day of the exposition. Goodhue was the chief architect. They wanted tolocate the exposition on the central mesa of Balboa Park. Allen liked the expansive site and thought it would be a more accommodating building site than the canyon-pocked southern edge of the park. Goodhue liked the idea of placing his buildings on the prominent, elevated land of the central mesa.

Allen and Goodhue lobbied ceaselessly for their preferred location and eventually persuaded the Building and Grounds Committee to move the exposition from the southern border of the park to the central mesa. John Charles Olmsted was away from San Diego when the vote was taken. When informed of the decision, he immediately telegraphed the Olmsted Brothers’ resignation from the San Diego exposition project.

Olmsted viewed this incursion into the heart of the park as a catastrophic mistake. He later wrote of the “outrageous disfigurement” San Diego had inflicted upon its urban park and never regretted his refusal to be a party to “the ruin of Balboa Park.”

A New Eden

Once shocked exposition officials accepted the finality of the Olmsted resignation, Frank P. Allen, Jr., who had unwittingly helped drive off the Olmsteds, took responsibility for exposition landscaping. A talented architect and engineer, he rapidly put himself through a reading course in landscaping and horticulture and absorbed enough information to make a genuine contribution to the landscaping of the exposition grounds. But with so many other responsibilities, Allen had to find help.

Paul G. Thiene, a young German immigrant with substantial horticulture training and experience was a low-level nursery employee during the brief Olmsted regime. When the Olmsteds resigned and reassigned all their employees away from San Diego, Thiene moved into the position of nursery supervisor. He began working closely with Allen and was eventually promoted to landscape supervisor for the exposition.

This little-known team of Allen and Thiene produced the memorable landscape of the Panama-California exposition. Their work was not easy. Most areas of Balboa Park could not be planted until dynamite was used to blast through the underlying hardpan. Irrigation and water systems had to be created. Large numbers of workers had to be hired, organized, and supervised in the race against the exposition’s opening day. Plants were raised on site or purchased. San Diego’s small commercial plant nurseries could supply only a limited percentage of the stock needed, so Thiene spent countless hours locating plant suppliers all across the country. It is estimated that more than 2 million plants of 1,200 species and varieties were used in the exposition landscape.

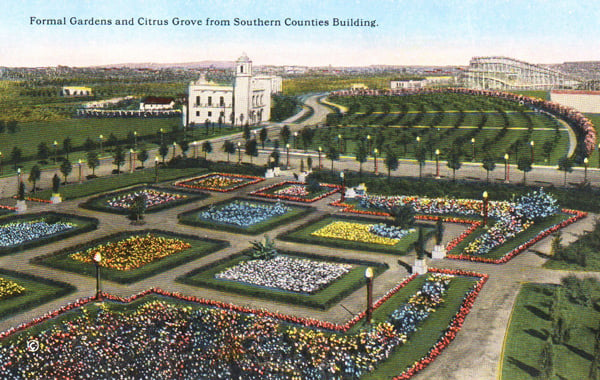

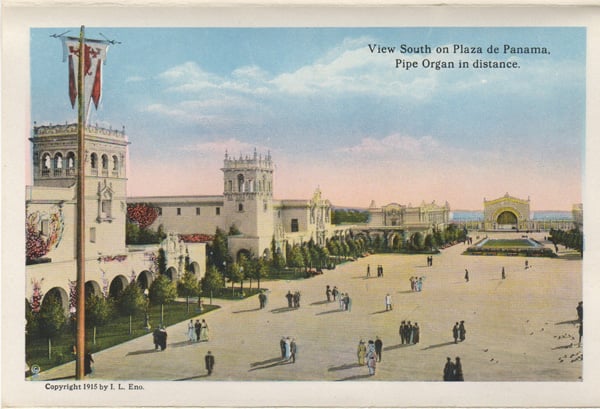

Out-of-town visitors were meant to find a new Eden in sunny San Diego. Ten thousand poinsettia shrubs were planted for the January opening, creating a display of bright red blooms when much of the nation’s plant life was dormant or buried under snow. Upon approaching the exposition grounds, the creamy and ornately decorated buildings rose like a magical city on the hill, protected by a surrounding forest of fast-growing trees planted down the canyon sides. Flowers and vines were blooming at all times and in profusion. Tropical bananas, cannas, and palm trees thrived. Pergolas dripped with bougainvillea. Large, formal flower gardens presented colorful displays. There were green lawns. The contrived lushness of the exposition grounds was maintained at the price of generous watering and the employment of overnight crews who replaced all spent or distressed plants and completely replanted flowerbeds.

The “Garden Fair”

“The planting of the exposition was fully as important as the buildings,” Frank P. Allen, Jr., wrote in 1915. Both the architecture and the landscaping captivated and enthralled visitors. “The floral splendors make this the greatest floral exposition the world has ever known,” wrote one observer. “No other place in the country could produce such a display.” The author of The San Diego Garden Fair captured the awe-struck wonder of so many when he described the exposition as a place where “a magic garden has taken the place of the desert.”

The horticultural achievement of the Panama-California Exposition brought near-universal praise and cast an influential green thumb far into the future. People carried away the message that anything would grow in Southern California and happily blurred the distinction between the region’s generally frost-free climate and that of a tropical plant zone. Subsequent generations of regional landscapers replicated the “garden fair” without concern for water requirements.

Lost in this romance with tropical and thirsty landscaping was the wisdom of Balboa Park’s first two professional landscape architects, Samuel B. Parsons, Jr., and John Charles Olmsted. Both found Balboa Park beautiful. They urged San Diego to make a regional statement by embracing and preserving its natural appearance. Both advised landscaping with climate-appropriate plants. They cautioned against filling the park with buildings or otherwise intruding on its peaceful natural setting. A final and lasting commonality between landscape architects Parsons and Olmsted is that San Diego largely ignored their expert, and expensively purchased, planning advice.

Why did these efforts gain so little traction in early San Diego? One explanation is that locals, living in a dry and dusty city, were in no mood to celebrate a park offering more of the same, however exotically beautiful the park’s scrublands and wild canyons appeared to Parsons’s and Olmsted’s East Coast eyes. Most people wanted a park that conformed to their own vague notions of how a park is “supposed” to look—filled with trees, green lawns and formal gardens. When the Panama-California Exposition delivered an exceptional example of this public park ideal, San Diego gardeners happily adopted the exotic plant palette. Only water crises of recent years have forced a reassessment of this approach.

Ideas about the uses of urban parks have changed. San Diegans fell in love with the beautiful Spanish Colonial Revival buildings of the 1915 exposition. Those buildings, reconstructed replicas, and other structures, while a further departure from the Parsons-Olmsted philosophy, now house the groups and institutions that make the park a center of culture and the arts in San Diego. Today, Balboa Park is one of San Diego’s most popular destinations, attracting up to 10 million visitors annually. In 2015, this famous urban park will commemorate the centennial of the event most responsible for transforming it into the landscape it is today.

Sources:

Richard Amero, Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition, ed. Michael Kelly. Charleston: The History Press, 2013.

Florence Christman, The Romance of Balboa Park, 4th rev. ed., San Diego: San Diego Historical Society, 1985.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses