Why Gardeners Travel; A Costa Rica Adventure

Contributor

- Topics: Nature is Good For You

Spring 2024

In Costa Rica, it’s hard to avoid seeing people looking for birds. This past January, I joined our Pacific Horticulture group for an early morning bird walk. I didn’t bring a telephoto lens and wasn’t expecting to get any close-up pictures.

Our small tour van guided us through the cloud forest of Savegre Valley. We were surrounded by wild avocado trees (Persea spp.) and had a good chance of seeing the resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno), the “plumed serpent” god of Mesoamerica that dined on the fruit.

Not 200 yards up the road from the lodge, we stopped the van when we saw another guide with a couple of bird watchers pointing into the trees. Quetzals! The males have long tails and are associated with the snake god Quetzalcoatl.

**All photos are by the author unless otherwise noted.

I noticed our tour guide, Carlos (Charly) Bolaños, was taking pictures with his smart phone through his spotting scope, and I asked him to teach me. It did not take very long to figure out I could very slowly position the lens of the phone carefully on top of the eyecup of a spotting scope. So long as the phone was locked into the infinity focus setting, the photos stayed sharp. Maybe not sharp enough for a glossy publication, but pretty darn good.

As the morning progressed, other birdwatching groups came down the road and realized this was the spot. We all participated in what the guides called the quetzal dance—as the birds flew from one tree to another, the birdwatchers shuffled along with spotting scopes and tripods.

I went to Costa Rica for the plants, having no idea that I would learn about bird photography, but now I have a new skill to bring back home to California.

As a photojournalist, I see the world through a camera and take pictures to solidify my memory. We travel to get our own insight into the places we visit, and the camera is the way I create my story.

We began our adventure at the Hotel Bougainvillea in Santo Domingo, just outside the capital, San José. I set out to capture the 10-acre garden that drew us to this hotel. Right away I was seeing more than the traditional travel brochure pictures of a hotel bedroom overlooking a garden.

We spent our first morning at the Green Ark Botanical Garden, where we were met by Tommy Thomas, the founder. I wanted a picture of him in context, so I backed off a little and framed him off to the side so that we could see him addressing the group.

The Green Ark Foundation’s “mission is to educate and share knowledge about the use of plants for a better personal life, and for the well-being of the planet,” according to its website. Here was a botanic garden dedicated to farming in the tropics.

Vist our Travel Page to see upcoming tours with Pacific Horticulture — Make your own stories.

Going into this trip, I think all of us knew the narrative of Costa Rica—that it is a very green country, with lots of ecotourism and well-considered land use. At the Green Ark Botanical Garden, we found out that the narrative of ecotourism was not a marketing gimmick, it has become a marketing tool, because taking care of the land has become a way of life in Costa Rica.

We got the equivalent of a walking TED Talk on the importance of ethnobotany and local farming. Crops in Costa Rica include banana varieties other than the Cavendish, which is 99 percent of all global banana exports, and the achiote shrub (Bixa orelllana), whose seed supplies natural red dye for lipstick and sazón seasoning.

Our tour of the botanic garden was followed by a very leisurely five-course garden-to-table meal in The Ark Restaurant that would rival any in Napa Valley.

We spent our afternoon at La Catalina Jardin Botanico with Randall Obsney, an expert of indigenous orchids of Costa Rica. Visiting this off-the-beaten-path small family business of local orchids is just the sort of nerdy off-the-wall place horticulturists love to discover.

I wanted to be sure to capture a picture of Randall himself showing off one of his orchids.

On Day Two, we set out in our small van to the tropical rainforest in Sarapiqui Valley. Elvin, our wonderful driver, knew just the place for a turnout as we crossed the Continental Divide from the Pacific side of the country to the Caribbean. This was literally his neighborhood.

Of course, the entire group wanted a photo of the beautiful Costa Rican countryside on this ridge. It was beautiful in both directions but, as it was still morning, the better photo light was looking east, making the vegetation more lively. We all piled out to the edge of a field and posed for a photo.

Our first stop on the day’s itinerary was the Nectandra Cloud Forest Garden, a truly remarkable research center to “promote the conservation and restoration of the montane cloud forest ecosystems of Costa Rica through its science programs, public education, and watershed stewardship,” according to their website.

Using conservation practices within and around the watershed, they help local farmers understand the value of ecosystem preservation, because without conservation the water will not remain on the land. The work at Nectandra has little to do with ecotourism (other than hosting tours, and a delicious café) but speaks to the culture of Costa Rica and the people who live with the land.

Here at Nectandra, because of the dense foliage of the cloud forest, it’s hard to get a photograph with a sense of composition. In this photo, notice how the silver star palm (Cryosophila warscewiczii) provides a solid anchor for the upper right corner. (See Before photo in the Nectandra gallery link in Resources.)

As we continued our drive to Selva Verde Lodge in the Sarapiqui Valley, Elvin kept a lookout for interesting sites that only a local would know. Being a horticultural group, plants and ecosystems were certainly the focus of our tour, but Costa Rica is also known for its unusual fauna, especially birds. He knew a spot where giant iguanas climb trees, and he spotted a three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus) stuck on a telephone pole. (We called animal services.)

This is exactly the sort of serendipity we hope happens when we travel, and it sure helps to have a guide who also knows where to look. Charly, our guide for the entire trip, has a degree in botany but also seemed to know everything about Costa Rica ecology. Once we’d settled in at the lodge, he led us on a night walk. By the light of a flashlight, he saw tree frogs and lizards, and he kept them in the light just long enough for us to grab a picture.

On our first full day at Selva Verde Lodge, we took a rainy morning hike in the rain forest. (The packing list provided by the tour company came in handy. I think all of us were prepared.) I wanted to have a picture that told the story of wetness while still getting a feeling for what Charly was telling us. In this picture, he was explaining the ecology of rainforest trees that have a buttressing system for the roots.

This adventure was followed by a midday visit to a chocolate farm, where we learned about the sustainable farming methods that led to a higher quality and better prices for the farmers. We also learned how to grind chocolate beans and add just the right amount of cane sugar to make our own 70 percent chocolate cream. On our way out, we nearly emptied the tiny gift shop of their chocolate bars.

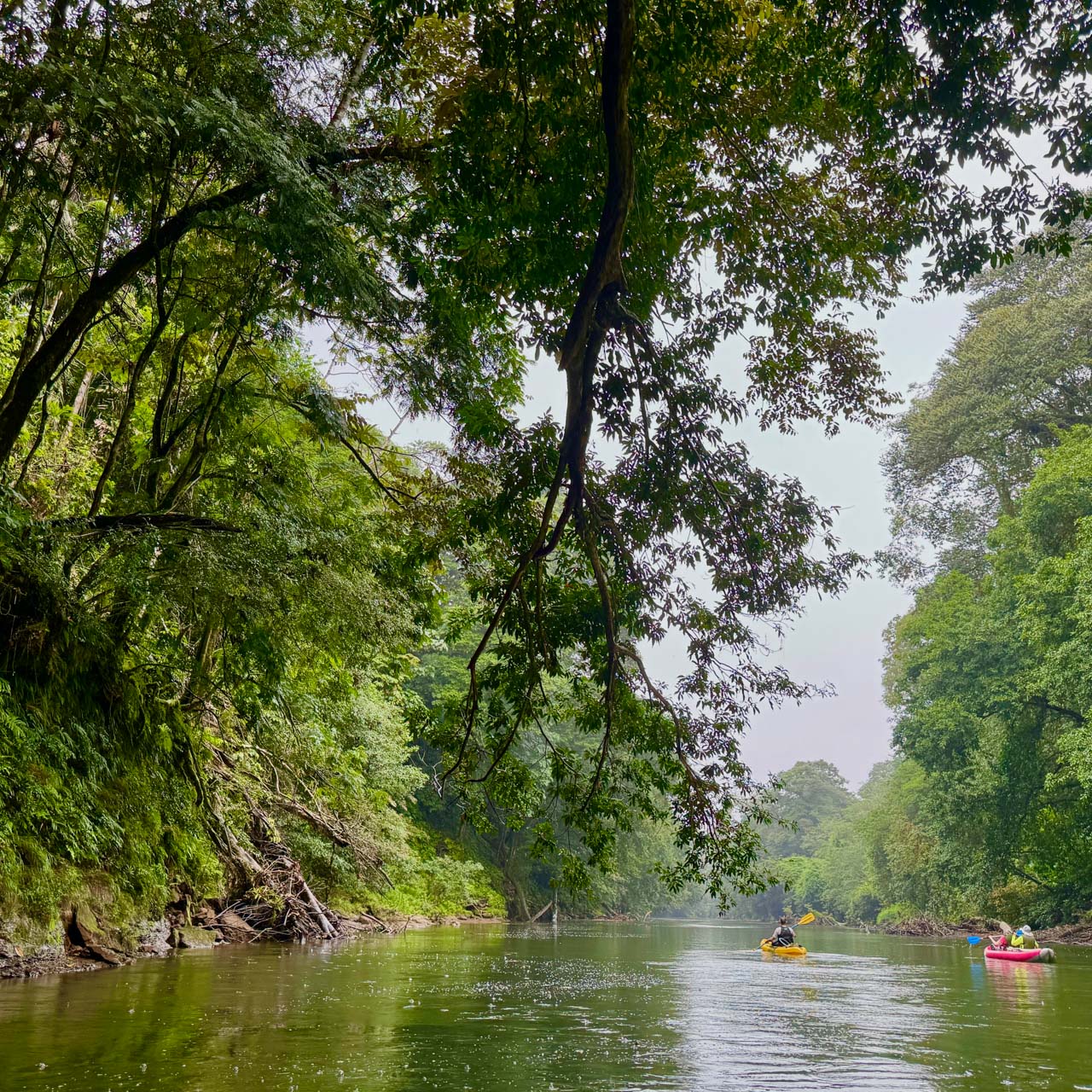

That afternoon our guide, Charly, had arranged river rafting with a buddy who ran a small river rafting company. We spent a magical afternoon on the Rio Sarapiqui in the rainforest during a warm rain. Not even halfway through our trip and we are already full of adventures and stories to tell—many, like this river trip, we could not have imagined.

Read Next: The Native Flora of Chile in The Traveler’s Garden at Heronswood by Dr. Ross Bayton

The native flora of Chile has long enthralled gardeners all along North America’s Pacific coast. This South American sliver of land is practically our mirror image in the Southern Hemisphere, with climatic zones that match ours, and therefore numerous plants that ought to thrive in our gardens. At Heronswood, our connection with this magical country is the result of several collecting trips made by our staff, beginning in 1998.

To capture something of that river trip, I wanted a photo near the edge of the river, where some of the rainforest could overlap the frame to compose the photo. We were two to a raft, and my partner was skilled enough that I didn’t really need to paddle or steer. I put my camera up to my eye and watched the view as the composition slowly changed until I saw the exact photo I wanted.

We spent the next day at La Selva Research Station of the Organization for Tropical Studies (OTC). Charly had met Head of Scientific Operations Orlando Vargas Ramirez during his own studies.

Charly explained that Orlando would be able to give us about 15 minutes of his time when we first arrived, then a staff member would give us a longer tour. However, once we all met, Orlando was excited to be meeting a group of plant people and gave us an hour of his time.

Orlando led us into the forest to see the vine Gnetum leyboldii, a plant which is a living connection between angiosperms and gymnosperms. The Gnetum vine was quite large and way up in the trees, making it difficult to get a picture of the plant, so I simply found an angle where he held up a piece of the “chicken bone” segmented stem with vine behind him.

Later that afternoon, on our way back to our last night at Selva Verde Lodge, we had a pleasant pontoon boat ride down the river next to OTC, looking for wildlife. Even though it was a rather quaint set up on a small dock with the local kids hanging out, I felt pampered, quietly sitting while the scenery passed by, the boat occasionally idling without the motor.

Cruising down the river, we saw lots of birds, we saw bats, and we saw crocodiles. We may have even seen a shadowy black panther, though very much unconfirmed. Exciting to know they live near the La Selva preserve. We saw an osprey dive and catch a fish while one of our fellow travelers, Nancy Gyes, an accomplished bird photographer, had her camera and telephoto lens ready.

The next day we headed south and crossed back across the Continental Divide into the montane cloud forest of San Gerardo de Dota in the Talamanca Mountain Range. As we headed down the narrow road in Savegre River watershed to the lodge, the view from our van was simply astonishing.

I did enhance the cloud highlights a little bit with the phone app, but the beauty is a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

The Savegre Lodge is surrounded by this cloud forest and owns almost 1,000 acres, including the site of the Centenary Oak (an award-winning Quercus sapotifolia). Oaks are easily my favorite trees, and I had no idea there were oaks in the tropics until settling in at a lodge in the middle of an oak cloud forest.

The next day, Charly led a hike into the cloud forest among the tall oaks. Even with a wide-angle lens, I had to back up quite a way to be sure I included the trees in relationship to the group.

At first glance the forest looked a little bit like an East Coast deciduous forest or even our California coastal forests in the green of winter—tall trees with lots of green understory—but immediately the plants told a different story.

Note how I composed this picture with one of the hikers in a red jacket a bit off center, surrounded by the lush green. I waited for him to walk right into that position before photographing the moment.

As we walked, Charly pointed out bamboo, palms, wild begonia, Bomarea (his specialty) with its distinctive resupinate leaf structure, twining African violets (such as Kohleria tigrida) and even found the root parasite Corynaea crassa—known as Peruvian Viagra.

The group did not have time to climb up the Los Robles trail to the Centenary Oak, but we had the afternoon to ourselves, so I got a Jeep ride halfway up, then climbed the trail to see this wonder at 8,563 feet.

To get this photo, I walked around and around the tree trying to find a branch pattern that separated from the surrounding forest. Then, using the widest lens, I placed my camera solidly against the base of the tree and looked straight up into the mist.

The same day that we joined other groups to do the “quetzal dance,” we went to Batsú Gardens, a nearby birdwatching preserve. The owners had birdfeeders stocked with fresh fruit, making it quite easy to get more photographs. I confess I was not great at setting up the spotting scope, but once someone helped, I got pretty good at lining up my iPhone with the eyecup.

The next day, it was time to leave the cloud forests of San Gerardo de Dota and head back home. I have left out many of our adventures: the gardens around the lodge, the meals and local food (plantain at every meal), the out-of-the-way stops such as “where the wind goes to die,” the plants in the forests, photo tips and conversations, and the howler monkeys.

On the last day, as we drove back to Hotel Bougainvillea and connections home, Charly wanted to take us to hike a small hill, a place along the Continental Divide to see both the Pacific and Caribbean oceans. However, it was cloudy, so Elvin drove the tour van up a gravel road to the highest point he could get us to—11,352 feet above sea level.

A wonderful story just our own, a side trip to the top of the world, something I never expected to see. We travel to expand our view of the world. Thank you, Pacific Horticulture for making this happen.

And as a final tribute, when we travel, we meet people and make friends. Thank you to my fellow travelers for lifetime memories and especially thank you to Elvin and Carlos, our enthusiastic guides.

Pura Vida! Costa Rican term to say hello, goodbye, everything’s great, and everything’s cool.

This article was sponsored by:

Resources

More photos of our stop at Nectandra in this link including the Palicourea pilosa leaf that uses the purple underside to gather reflected light in the dense cloud forest. Who knew?! Reinforcing the reason we travel—to learn cool stuff.

Responses