What if Farmland Looked Like Ecological Gardening with Garden Futurist Tim Crews

Contributor

- Topics: Garden Futurist

Summer 2023

Listen to the podcast here.

If you knew it would reduce erosion risks, sequester more carbon, require less fuel, fertilizer, and pesticides to grow them, would you eat a new perennial grain?

The Land Institute states that: “Our science has demonstrated that new perennial grain crops can be developed, and that diverse, ecologically intensified cropping systems hold the potential to bring grain crop agriculture to a level of ecological function on par with native grasslands and other natural ecosystems.”

Garden Futurist spoke with Tim Crews Chief Scientist; International Program Director, Director of Ecological Intensification at The Land Institute to find out how ecological perennial gardening ideas could scale up to vast areas of our agricultural landscapes.

This episode was sponsored by:

Sarah Beck: You’re listening to Garden Futurist, I’m Sarah Beck here with Adriana López-Villalobos. Hi, Adriana.

Adriana López-Villalobos: Hi, Sarah.

Sarah Beck: And we’re talking about my interview with Dr. Tim Crews, chief scientist at The Land Institute. I have to share their statement of purpose because it is so Garden Futurist:

“We work for a future in which humans flourish as members of a thriving ecosphere.”

I totally love ag, so it doesn’t take a whole lot to make an excuse to talk about this. When we talk about how much land is being used for different purposes, and you look at the stats on how much is farmland, the numbers are overwhelming.

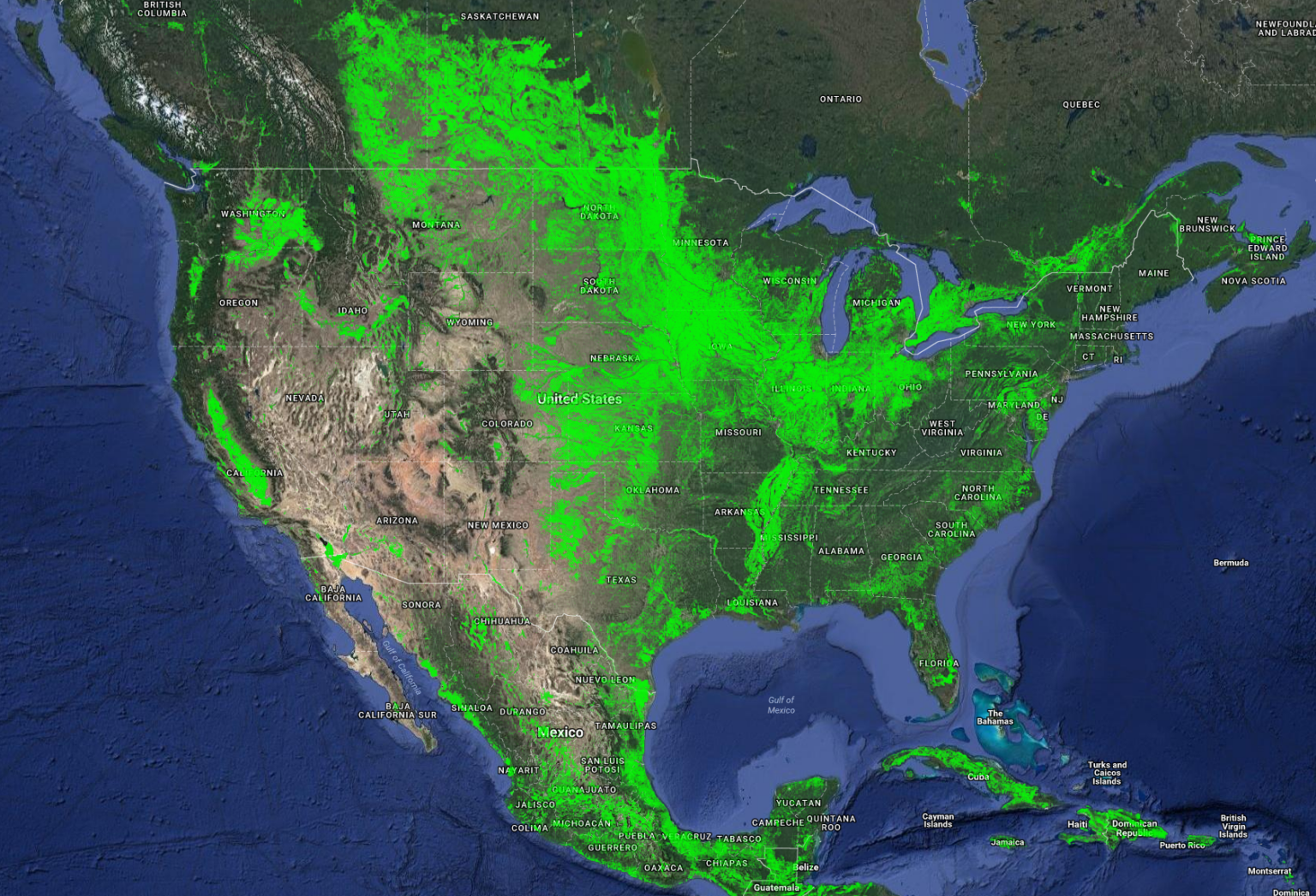

There’s a wonderful map that the US Geological Survey has of cropland across all of North America. You can see basically, Mexico to Canada, all the cropland and it is just a huge area. It’s something like 25 percent of the total land area of the Americas.

Adriana López-Villalobos: It’s interesting to put it into perspective, the situation with grains, right? Like, how much of that land is used for grain crops versus other types of crops and monoculture versus polyculture? How much diversity is contained into those different kinds of agrosystems, right?

Sarah Beck: Totally. The thing that’s really neat talking to people from The Land Institute, here’s this opportunity to bridge agriculture conversation with a gardener conversation and an ecology conversation.

I’m going to use that term, gardening the earth. Thinking differently about how we manage growing plants for food, and thinking about that in the same way that we think about, say, restoring a landscape or even gardening with the ecology. You start seeing this relationship there.

Adriana López-Villalobos: The connection with a microscale, like what we know about gardening at a more local level, more fine scale, and then you can talk to these people, and they have that knowledge plus what is required for large-scale agriculture. And then you can start seeing those pieces that come together and say, “Why are we not doing that? What are the pieces missing to translate into that,” right? Like, we need to feed a huge population. We don’t have a lot of resources. How do we move from something that will need to be scaled up but be sustainable at the same time, that incorporates diversity, that incorporates the richness of the soil, the microbes, the everything?

Sarah Beck: I think all of us as gardeners have this thing in the back of our minds all the time. Yes, we’re talking about all these spaces that are relatively small, and every time somebody is in the room and says, “Well, what about the acreage in this world, and especially in this country that’s devoted to agriculture, are we just going to pretend that doesn’t exist?”

Tim Crews: Yeah. It’s the vast, vast majority, right? I mean, it’s incredible.

Sarah Beck: There’s a quote that you say that The Land Institute “is the most focused and far-reaching of any organization.” Can you give a little bit of just framing or context to this idea that is behind the work of The Land Institute?

Tim Crews: On the one hand it is very broad in that it’s our mission to address how we as humans live on the Earth. For the last 10,000 years, anyway, the majority of our food has been grown with a particular type of ecosystem that is very unique, does not really occur outside of human agricultural landscapes. And that is one of

course that’s reliant overwhelmingly on annual plants. There are perennial crops out there and there’s perennial agricultural systems. But in terms of the calories that support humanity, the vast majority come from cereals and pulses and oil seeds, and almost all of those are annual crops, crops that you have to plant every year from seed.

We’re kind of trying to address a huge aspect of who we are as a species on the one hand. But it’s funny because when people go, “Well, then what are you doing?” And like, “Well, we’re breeding perennial grain crops,” and that just sounds like such a narrow niche to a lot of people.

Like, “Oh, well that’s interesting. What else are you doing?” And like, well, actually, you know.

Sarah Beck: That’s kind of a lot.

Tim Crews: We haven’t been in the business of developing new cereals for thousands of years, really, ones that are large players in the landscape in terms of crops that we grow, and there’s a reason for that. It’s a very, very slow process to develop a new grain. Not to mention that we have never developed a perennial cereal that is high yielding as a cultivar, like any of our annual cereals. Cereals being the grasses—corn, wheat, rice, barley, oats. It’s both extremely broad and ambitious of an undertaking, and it’s also very oddly narrow in its scope.

Sarah Beck: Let’s back up just for a second. Can you really briefly summarize just some of the issues with the annuals? I do want to get right into what is amazing about the perennial crop idea, but why are we even asking that question?

Tim Crews: It’s interesting, one, to note that the vegetation that makes up virtually every major ecosystem on the planet—every natural ecosystem like forests and grasslands and tundra and desert and savannah—are overwhelmingly, it’s just not 100 percent, but it is the dominant vegetation type of perennialism that defines those vegetations and they’re diverse. You don’t typically have one species. There are always examples of strange sagebrush stands or something that is one perennial, or you will have a rare instance where an annual is kind of recurring over many, many years and does not get replaced quickly by perennials. But those are very, very small exceptions on a global basis.

So that’s an interesting data point just because those are the ecosystems that actually built the soils that we farm today. When we’re in the Midwest, it is not corn (Zea mays) or milo (Sorghum bicolor) or soybean (Glycine max) that actually built these beautiful mollisol soils. Mollisols being the title or the name of a deep grassland soil with a rich A—or organic—horizon.

That organic matter in that deep surface horizon is made from investments of many, many species of roots over time. It develops a structure, and it allows for infiltration of water into that soil and microbes live there very deep. It’s a whole ecosystem. We call it a soil ecosphere, in fact.

So that’s just really important to note that soils themselves were not built under annual vegetation. Because we selected on cereals that are annuals, we need to kill every plant virtually every year on the landscape to make it so that our little annual grain seedlings can survive. They’re not very competitive with perennial background vegetation, so you got to knock everything off and plant your cereal.

In the meantime, if there’s stretches of time when there’s virtually no plants on the landscape, if a hard rain comes—like it inevitably does in the spring—you’ll have massive erosion at far greater rates than the rate of replacement, than the rate of soil formation. We’ll have nutrient loss.

The dead zones at the mouths of major rivers, like in the Gulf of Mexico, is nitrogen runoff from the Upper Mississippi basin. It’s just those agroecosystems are leaking nutrients because there’s no roots in the soil to take them up.

The whole existence of weeds, I mean, weeds grow—as us horticulturists know—that they grow when there’s light or nutrients or water, soil resources or sunlight that is underutilized by the crop or by the plant that you want to be growing in a certain place. So weeds are oftentimes relatives of our crops that gladly show up and take advantage of underutilized resources. So just picture a field that’s denuded of vegetation in the springtime before you plant your crop. That is the biggest possible welcome mat imaginable for weeds.

As humans, we’ve spent an inordinate amount of our last 10,000 years literally hoeing and plowing and killing and pulling that competing vegetation. So there’s so many shortcomings of agriculture, of crop production that can be linked to the fact that they are annual species.

Sarah Beck: You made a great case against the annual crop.

Tim Crews: And it’s so much work. It’s so much work.

Sarah Beck: It’s so much work. You’re spending all your time killing stuff.

Tim Crews: You know, in the last 150 years we’ve gotten—in some cropping systems, especially grains, a lot of that work energy to do that is provided by fossil fuels, to the tune of 99.96 percent of the calories to grow food is provided by them. It’s in synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, it’s in tractors, it’s in all these inputs. Now that we’re trying to back out of that carbon dependency, we have to think long and hard about how to make the agroecosystem grow itself more.

Sarah Beck: Now you’ve got me really excited to talk about perennial plants. Let’s do it. So I do want to quote from the National Academy of Science, because who doesn’t love to hear from them. This is from a National Research Council 2010 statement:

“Perennial plants reduce erosion risks, sequester more carbon, and require less fuel, fertilizer, and pesticides to grow than their annual counterparts,” which you basically just said. “Perennials have greater ability to maintain the health and fertility of a landscape over longer periods of time.”

To jump right into The Land Institute’s statements on this, because you all are doing a ton of research, you have said, “Our science has demonstrated that new perennial grain crops can be developed and that diverse, ecologically intensified cropping systems hold the potential to bring grain crop agriculture to a level of ecological function on par with native grasslands and other natural ecosystems.”

That statement gives me chills. It literally does. I’m curious if you could break down for us a couple of the big research challenges and some of the elements of this.

I know you’ve already mentioned breeding. I think we all get excited to hear that story about those first—I actually think a breeder told me recently, these were likely women. We go back to that 10,000 years ago, someone making select seed selections of precursors to wheat (Triticum spp.). This is such a cool story, but you’re saying it takes a long time.

What are the big challenges? What are the pieces that need to come together in order for us to actually move forward on an idea like this?

Tim Crews: The breeding work is paramount. The amount of time and the work involved in developing adequately yielding perennial grains is really the biggest challenge.

We at The Land Institute have been using two approaches to do it. One is to domesticate wild species. They start just like 10,000 years ago, what you were describing, those original selections.

Those original selections were probably inadvertent breeding in that you go out and select on plants, for example, that don’t drop their seed at the end of the year when most wild species want to drop their seed, they want to spread it and not like fall over and have all of their offspring all clumped up germinating right together. So a very original domestication trait is called non-shattering, and that’s selecting on plants that don’t drop their seed.

Just the act of going out and collecting plants that don’t drop their seed selects on the genes for not dropping your seed. So while people were not even thinking that’s what they were doing, you resow that seed. Little by little, generation after generation, you come up with a plant that does not drop its seed at all, and you haven’t even increased the yield of that plant, but you’re harvesting far more food out of the same area. The people doing that work didn’t even realize, they did not know they’re shifting the mean genetic makeup of this wild wheat in doing this.

That is the approach that we’re working on with perennials now, is we’re selecting on plants that have basic traits of not dropping seed at the end of the year, of increased seed size, yield, the stature that can handle heavier seed heads and not fall over so it doesn’t lodge.

There’s a list of actually about 20 traits of interest, disease resistance, all sorts of things. That process is just very iterative. You’re not going to make a grain, a new crop overnight. Even with really cool modern molecular techniques, and I’m not talking about genetic engineering here, per se, but more genomic selection where you use information about the genetic makeup of the plants to select in them. You look into the DNA of the plant to tell you if it has some of the traits you’re looking for, even before you grow it out.

So we’ll plant 10,000 seedlings, send those leaves from every seedling off to Kansas State University, and they send us partially sequenced data that tells us right off the bat if it has some of what we’re after or doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, we get rid of it.

So we only have to grow out maybe a fifth of the plants that we actually sow, or even less. That saves so much time to then just concentrate on the plants that have promise. So we have cool techniques that can really accelerate this domestication work, but it’s still very, very slow.

The other approach, though, is more of kind of a rolling-the-dice technique, which is wide hybridization, in which we will take an already existing elite annual grain like wheat or sorghum (Sorghum spp.). Our colleagues did this with rice (Oryza sativa x longistaminata) in the Yunnan province of China, and you cross it with a perennial relative of that annual elite crop. What you’re trying to do is just bring a little bit of the perennialism in. Enough to make that annual essentially become a perennial while maintaining a lot of the attributes of the original annual, like seed quality and yield and things like this.

That is a whole different game, because you can develop a perennial relatively quickly if you roll all sixes, right? And it’s just a matter of continually trying, but you may never roll all sixes, either. And so it may be a much faster approach than domestication, or it might be much slower.

Our colleagues in China did roll all sixes, or at least five out of six sixes with rice. And there is now a high-yielding perennial rice.

Sarah Beck: Is that using some of these more traditional techniques or would genetic modification help a process like this? Like the CRISPR or some of this new technology?

Tim Crews: They did that with just basic crossing, modern crossing. There is interest in using CRISPR in some of this work. We don’t do it ourselves. We do have some colleagues in Denmark who are looking at trying to identify the genes responsible for some of the domestication traits we were just talking about with CRISPR.

If they do find it using CRISPR by knocking out genes and proof of concept that they know what is controlling this trait, then it becomes a discussion amongst the breeders about whether to use those modified plants, or go find that mutation in other populations.

Sarah Beck: Oh, because that would help you identify what the mutation is.

Tim Crews: Exactly. Exactly. We haven’t crossed that line yet. because they haven’t really been successful at this point, but they’re working on Kernza or intermediate wheatgrass as well as perennial barley (Hordeum bulbosum) in that lab in Denmark right now.

At The Land Institute, we’re using conventional breeding techniques, but as I just described, with these enhanced DNA-informed genomic selection methods that are really powerful because you can select on like 20 different things at once.

Sarah Beck: You just mentioned Kernza. I’m curious about some of the promising perennial plants, and you also were just mentioning sort of more familiar cereal grains that could be looked at. We know, especially in the Pacific region, there are a lot of Indigenous perennial crops, there are Indigenous cultures that utilize them. I’m curious kind of how you look across what the options are to even start with finding a plant that has promise.

Tim Crews: Yeah. We’re really encouraging anybody and everybody, if they have an interest in a particular perennial species to investigate, and maybe give it a try and work on selecting for particular traits that are of interest. Like in the Northwest and elsewhere, there’s lupines (Lupinus), perennial legume, that looks very promising and it does not do very well in Kansas. So we’re not, ourselves, actively working on it right now. But I just learned that there is a group in Canada that is working on perennializing lupine.

Sarah Beck: Has anybody ever eaten lupine? Is it good?

Tim Crews: Actually, yes. I mean, as an annual species, and there are annual lupines. I have had the opportunity to visit Bolivia before, and they are served up on the street in little cups that you can just eat like a snack.

In Australia, they actually worked on lupine to eliminate some of the secondary toxic compounds, and it was developed as an animal feed. So lupines definitely have a history of being consumed by mammals, ourselves included, but not developed as a perennial grain that could be harvested consistently. There’s a number of attributes that need to be improved on to make it into a crop from a wild species.

Another one that we’re working on is (Onobrychis viciifolia). That’s a forage legume that produces a lentil-like bean. And it’s been named Baki Bean. That’s the Kernza-like name, the trademark name of the seed that’s produced by sainfoin. Sainfoin has been known as a semi-drought-tolerant legume forage crop, like alfalfa (Medicago sativa), but it produces a much larger seed. We’re on the verge of having it approved as having grass status, which is generally regarded as safe so that it can be consumed by people, at least in the US.

Another domestication project that we have is with Silphium and its name is silflower. Silphium’s the genus, silflower the seed. That is an oil seed that would replace sunflower, for example. And it’s a very deep-rooted native of the prairie this part of the world, and it’s extremely drought tolerant and a very exciting crop.

We do have a lot of problems with pests and Silphium just because we’re right in the native habitat of it and it’s a mixed blessing, but we’re learning to work on crop protection ecology and genetics to defend Silphium as a new crop against a number of native pathogens and insects that really like that genus in particular.

Sarah Beck: So I’m really curious about this element of it, and I know this is like looking way down the line, because by the time you get something into somebody’s grocery store shelf, for instance, there’s a lot of things that have to happen before that moment. As you’re at these early stages, are you also thinking about, “Is this going to be something that people will feel familiar enough with, or is it going to require a cultural or a food culture shift in order for people to accept?” Do you have to go, “Okay, well we just make this similar to something you already know and, and therefore you would accept it.”

I’ve enjoyed some Kernza beer. I thought it was just fine.

Tim Crews: That’s a good example of kind of a replacement or substitution that is fairly unnoticeable, almost. And I think that it’s going to be a mixed bag. Baki Bean, as an example, this pulse legume may prove to be something that people want to eat as like a lentil substitute. It, to me, tastes a little more like black-eyed peas (Vigna unguiculata ssp. unguiculata).

But it would involve some cultural adaptation, there’s no question. It’s an interesting question how you introduce something like that that is culturally appropriate and desired. We don’t make the assumption globally that all crops are going to be desired or even appropriate all over the place.

So we expect different groups of people, different cultures, to work on the perennial crops and introduce them that seem appropriate to different regions.

The Baki Bean also has the potential of being a plant protein source. And we know that plant protein flowers are going into all sorts of products. And that’s going to be an example that’s more like Kernza in beer. You could substitute for pea flour, in making an Impossible Burger or something like that. But it’s a perennial legume, which will have far greater ecological benefits than peas or soy or some of the annual pulse crops they currently provide, these high-protein, plant-based sources.

So, yeah, we have different ideas for how some of these species might enter the food chain. It’s a great point, though. I mean, we think about it all the time.

Kernza has been a remarkable test case to see how the public reacts. It does resemble wheat closely enough that it can be folded in as a kind of wheat substitute or a complement. So for like pizza dough or pasta noodles.

Sarah Beck: I think this is interesting though. I mean this question of people accepting some of these new grains because there’s just so much benefit.

I’m curious if we could just jump to this sort of the magical part of this story, because if we can accept this idea of maybe eating something that’s a little bit different, the benefits of this are incredible. And when you talk about just what this could mean with perennial grain crops in ecological context of farming. You talked about successional gradient. So can you talk just a little bit about that, what you’re talking about there and just also some of what is so incredible about this idea of enriching our soil, instead of destroying it?

Tim Crews: Well, I appreciate that question, Sarah. It’s right at the heart of the work that I do. I like talking about succession and the ecological concept of succession because it’s so relevant to this annual cropping system.

When there’s a huge disturbance that seemed, like a landslide, or a really devastating flood, or a really devastating fire. A fire that kills every plant, not just that resprouts some vegetation following a fire and can actually benefit a forest, but one that literally knocks it completely down. That’s restarts what ecologically is known as succession, sets it way back to this disturbed state.

And it’s even more dramatic in agriculture where you till up the ground, I mean, some of these disturbances might even just deposit some sediment or some ash. But what we’re doing is literally scraping the ground and exposing it to loss of nutrients and carbon like I’ve described.

And then in ecological succession, colonizing plants, oftentimes annuals, come out and they grow for a few years, and they hold the soil enough so that then perennial vegetation starts to establish. Annual plants typically lose out to perennials, just because perennials get the light early in the growing season once they’re there. Just think of a forest in the Northeast unfurling its leaves on around like May 15, and then it’s like, no light gets to the forest floor.

So if you’re an annual, or if you’re an annual plant here in the prairie, you’re not going to grow. You have no chance to compete with these perennials that are fully established.

But annuals play a really key role in those very, very first years of succession. And then succession is simply the change of the vegetation moving into a more mature perennial system, oftentimes more diverse. That’s how nature works.

Soils are developed that way. Would they develop in that, under those annuals? No, they would not nearly like what we see out in the world. It takes these perennials to hold it, to feed it carbon with huge root systems, et cetera. And so in agriculture, we arrest the ecosystem in that very, very early stage of succession. With that arresting comes all of these problems that we’ve been talking about, of nutrient loss and carbon loss and soil erosion and weeds and all of this stuff.

So if we allow agriculture to move down the successional gradient in the same way that a natural system does following a disturbance, you’ll want to hold it at a certain spot. You don’t let it go all the way because then you kind of turn it into a forest that might be mostly dying as happens, because even natural systems will reset themselves eventually with disturbance.

But if you let agriculture go down the successional grading a little ways, then you have a highly productive ecosystem that is often diverse and it is able to basically grow itself year after year after year. You might disturb it with fire. You might disturb it with grazing. And the humans will be doing far less of the work.

I mean, it’s more like nudging the system than resetting it every year, is what we’re envisioning. When we talk about developing these perennial grains, we’re definitely not interested in simply replacing annual monocultures with perennial monocultures. That is not where we’re trying to end up.

Having perennial grain crops affords a whole new menu of opportunities to assemble highly functional ecological plant communities, if you will, So the first simple example of that is putting a legume in with a cereal, a grain. And we do that quite a bit with Kernza now and alfalfa. Annual systems, these bicultures or polycultures, go way back, the three sisters in corn and squash. The bean and the corn get along famously. So we’re doing the same thing with perennials, but it’s a very different ecology.

In the case of a rotation that might have a legume like vetch (Vicia spp.) or a clover (Trifolium spp,), an annual clover that you plant in rotation. You plant that legume, and then you terminate, disk it into the soil, it kills it, and it starts to decompose and release its nitrogen, and then you plant your cereal and you’re able to take advantage of this flush of decomposing plant matter that releases nitrogen. That was the cover crop.

In a perennial biculture, that alfalfa is not giving up its nitrogen very quickly. I mean, it’s not like you’re killing it and it releases the whole plant’s nitrogen. In fact, for a year or two, that plant is developing itself and using almost all of its nitrogen to grow and get larger and deeper deep roots.

So it becomes a bit more of an ecological predicament as to how you develop a diverse cropping system that can, for example, supply its own nitrogen. And this is something we’ve been working on quite a bit. We call it ecological intensification. In contrast to input intensification, that is what happened, for example, in the Green Revolution and industrial agriculture in general, where we use inputs to prop up the production of the cereal.

So we have a number of techniques that we’ve developed of planting a field of alfalfa for two years, for example, and then maybe undercutting strips in it so you have alternating rows of soil, and then alfalfa, soil, alfalfa, and planting Kernza after two years, after it’s established a pool of organic nitrogen in the soil. It’s being released at a more regular rate for the cereal crop to take advantage of.

And then all of a sudden we have this inner crop rotation, it’s like rotational intercrop, and that has proven to be remarkably productive with very little weed pressure, a lot of nitrogen input. And you go out and you harvest the grain and it resets the system and then you harvest the grain the next year. It’s a very simple but early version of a polyculture.

Sarah Beck: So can you use typical farming equipment to do this? Like this experiment you just described, are you using fairly predictable? It’s a tractor, you mentioned a disk. I mean, we’re not plowing things because these are perennials, right?

Tim Crews: Right, right. So for the most part, in the system that I just described, we will use an intercrop mower and that will mow down the alfalfa in between the rows.

So there are some innovations in equipment that are being looked into. But for the most part, the equipment’s the same.

Sarah Beck: You’re keeping that idea that this has to be manageable with reasonable equipment.

Tim Crews: Absolutely. And I just want to emphasize that if you replace an annual monocrop with a perennial monocrop of Kernza, say. That move does have some ecological intensification because annual cereal production loses on the order of half of its nitrogen right now. And again, it either goes into the water bodies or it can go up as nitrogen gases, including nitrous oxide, which is a very, very potent greenhouse gas.

Agriculture is the biggest source of nitrous oxide and it’s a huge problem and it happens when you have these big pools of synthetic nitrogen, or just nitrate, I should say, wherever it came from, sitting around in the soil.

If you develop, though, an intercrop, not only do you not have to put on twice as much nitrogen—because you already know you’re going to lose half of it, which is what we do with annual cereal production—but if you have the legume adding that nitrogen in organic forms gradually—it’s what we say mineralizing or decomposing, it’s being released gradually—then the plant demand and the supply by the legume synchronize much better. You just don’t even have nearly that nitrous oxide emissions issue if you can design a functional anchor ecosystem like what I’m talking about here.

So that’s just the one illustration of what may be possible in being able to use these perennials in ways that we have never had before to design just more functional ecosystems that are not only maybe going to be more resilient in the face of climate change, but mitigate it, as well.

Sarah Beck: Wow, this is amazing to think about and it’s very cool to imagine what the landscape would look like and what it would be like if vast swaths of the country we live in were converted to this type of farming. I just want to jump to my perspective and represent our audience of gardeners, and even urban people here. Because I think we talk so much about urban ecology and we’re really focused on these green spaces in urban environments. And I think, for those of us who are really excited about this work and climate resilience and ecology, I think there’s a lot of potential advocates for this work you’re doing,

Tim Crews: We do have a civic science program, and if people are interested in trying to grow a number of our other species that we’re working on, if they’re curious, we’re curious too, because we cannot go trial them in all of these new environments that we’d like to know about. And we just really don’t know the geographic extent, where they will grow, what the diseases are they might get, what kind of yields they obtain, whether they’re really perennial in a different setting.

As you mentioned, a legacy of Indigenous crops, Indian ricegrass (Eriocoma hymenoides) was one that would be in the Intermountain West, that is really fun to grow. Down in the Southwest where I lived in Arizona before coming to Kansas, there’s quite a few species that were used by most of the peoples that lived in northern Mexico or Southwestern US, the ancestral Puebloans. Wolfberry (Lycium spp.) was a plant, mesquite (Prosopis spp.). Prickly pears (Opuntia spp.)—certainly nopales and tunas are used a lot these days, and those are really great perennial food crops.

So yeah, I think just as gardeners becoming aware of what’s possible in the perennial world and experimenting with it, I just encourage it and certainly invite people to sign up on our site if there’s interest.

You were asking what will it look like, a landscape that is perennial.

The earth can handle scrapes here and there where we might open up a patch of land, farm it for a few years, and let it heal. It’s really not a big deal, but when we have over 8 billion people on the planet and over 12 percent of the Earth’s surface is opened up every year, and it’s some of the best soils, and they’re degrading very fast, then developing a new aesthetic of seeing green or brown, just diverse landscapes—kind of like the prairie that we have here in Kansas—is what we need to do.

In some cases, we may shift more towards tree crops or alley cropping systems that involve woody perennials quite a bit more. But getting a landscape that is covered year round with plants with roots in the ground is just the aesthetic I think we need to shift towards more and more.

Sarah Beck: This is why I think especially the ecological gardening folks are definitely a crowd for this, because I think we already associate what feels like wild land as being our special connection to the landscape, right?

So if you’re really excited about wild landscapes or the ecology of your region, this idea of farmland looking a little bit like that, that’s fascinating. We need to employ some artists to do some renderings. Has anybody done that?

Tim Crews: I would love to see that, too. I think that would be valuable.

Sarah Beck: It really captured my imagination, just that idea that there could be an element of a gardener’s mentality or an ecological gardener’s mentality being blown up to massive scale across our country, and that food could be produced in a really sustainable way.

Adriana López-Villalobos: Yeah. The other factor that like for me just blows my mind is that if we think about like how many plant species for crops we use, there’s very little, compared to the amount of plant diversity and plant good resources.

Sarah Beck: Yeah, no kidding.

Adriana López-Villalobos: If we start incorporating those other species into the mix, then perhaps there’s also there the solution or at least like one piece of the puzzle that can be brought in.

Sarah Beck: One of the things that really also struck me was just that openness to talking about exploring cultural traditions as a source for some of these plants. That’s really intriguing, too, because there are so many perennial plants that could be real crop plants. And who knows? I mean, there may be Indigenous knowledge that exists throughout our region that hasn’t even been tapped for thinking about this.

Adriana López-Villalobos: Yeah, and that can be shared. Like I see every time I go to the farmer’s market, there’s this new stand. Indigenous people from Latin America have been given a stand in the farmer’s market and they are bringing plants that I am familiar with because of my background.

Like I see verdolagas (Portulaca oleracea), which are the purslane, it is basically a weed, and we consume that here. Pumpkin flowers (Cucurbita pepo) that are also used in the Mexican food, and they start being like promoted in this farmer’s market and people ask about them. It’s something easy to incorporate into our diet. Some of them are already part of the crops, some of them are not, but are growing in this region or the habitat.

So I think it has to do with education, but also, probably as you said, like tapping onto the Indigenous knowledge.

Sarah Beck: The breeding piece is really special and I think for us to both recognize the value of plant breeders in horticulture and how much they do for us and how much they’re thinking about in terms of building resilience. So much of it is appreciating plant diversity.

It’s interesting because we just had this article that Rachel Spaeth wrote about Luther Burbank and it really sparked this conversation about just the important role of plant breeders and how many different ways plant breeders really are part of the importance of what we do in our community. Just to hear about how many different researchers around the world are looking at this problem differently and trying to use at least some of their innovation to help narrow down what they’re going to try. Because again, you have to grow things to try.

Adriana López-Villalobos: All these ramifications of the same question, right? All the different ways you can look at it and find answers to many different components that overall contribute to answer the same question. It is really interesting how now with the next generation sequencing, and all these new techniques for plant breeding that you’re mentioning have now been incorporated into growing, it’s mind blowing to think about growing a perennial grain

Sarah Beck: It is. It is mind blowing.

We’re just now about to release the third chapter of our story about the climate-ready landscape plants with our video series. And I was just up at University of Washington and I got to meet some of the grad students who are working in plant physiology and to hear them talk about what they’re looking at in terms of all these plant physiological traits that are going to help a plant cope with future conditions. This totally relates to this breeding idea because there are so many incredible discoveries happening right now in the world of plant breeding.

Adriana López-Villalobos: But they are all connected if you think about it. Ecology with breeding, physiology with breeding, and then biodiversity of all the different plants species or within a species diversity. It’s connected.

Sarah Beck: It is connected.

Resources

The Land Institute has more information on civic science and perennial rice.

Savanna Institute is a Wisconsin-based sister organization to The Land Institute.

Exposed: The Secret Life of Roots at the United States Botanic Garden

Responses