Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Garden Futurist

Mary Comber Miles was perhaps destined to be involved in the worlds of botany and horticulture. Her grandfather, James Comber built the renowned Nymans Gardens in Sussex, England, in a creative partnership with the owner, Ludwig Messell, and later with his son, Leonard. Mary’s father, Harold F Comber, a horticulturist and botanist, collected plants for a syndicate of garden owners including the Messells. He travelled twice to the Andes and to Tasmania seeking new plants that would prove hardy in British gardens. Encouraged by her school and family, Mary applied for a scholarship to The Cambridge School of Art for a grounding in art that would lead her into the field of botanical illustration. She has since had a distinguished career as one of the West Coast’s top botanical illustrators. She provided these reminiscences as she assembled an exhibit of her work for the Helen Crocker Russell Library of Horticulture at Strybing Arboretum.

In 1997, I visited Chile and Argentina, attempting to follow a little in my late father’s footsteps. In both countries, I was lucky enough to be face-to-face with many of the plants, or their offspring, that appeared in his published field notes. I confess that chills ran up and down my spine whenever I realized I was standing in one of his campsites or when I matched my photographs to his so many years later.

One of Father’s successful collections was Embothrium coccineum, the hardier Norquinco Valley form that is widely grown in Britain and in my own small garden near Vancouver (Sunset zone 4, USDA zone 8). My twenty-foot tall tree has once been nipped by early frost and by a particularly hard freeze, but survives still. With summer irrigation in the Bay Area, embothrium makes a superb small evergreen tree, each branch decorated with scarlet flowers in late spring. In its natural setting, it offers brilliant color to light up the forested mountainsides clad in southern beeches (Nothofagus spp.) and araucarias.

Father also collected seed of winter’s bark (Drimys winteri) and its smaller sister, D. andina (formally D. winteri var. andina), and introduced the latter into horticulture. I know it to be a reasonably hardy shrub, with fine dark green foliage and creamy-white-flowers, and feel it would be a possible rhododendron companion in Vancouver. Berberis linearifolia and Alstroemeria ligtu were two more of his collections. While I did not see the alstroemeria, I did see the barberry many a time, struggling for dominance in the forest. In a garden, it can be splendid covered with orange-yellow flowers.

One unforgettable evening I was taken by a Chilean boatman from Caleta Gonzalo (opposite the island of Chiloé) up the Reñihue Fiord to stay as a guest on the ranch of Doug and Kris Tompkins. Dusk was falling fast along with heavy rain. Neither the boatman nor I spoke each other’s language during the hour’s ride over milky, turquoise-green waters to the flats at the head of the inlet. The fiord was banked on either side by large ferns below a towering forest of mixed species. Tall trees of Eucryphia cordifolia were resplendent, clothed in white flowers against their fast darkening companion trees—much as our Pacific dogwood (Cornus nuttallii) presents itself here. An epiphytic bromeliad, Fascicularia bicolor, was bursting like so many firecrackers on the trunks of trees not far above sea level. I’ve always been envious of California gardeners who can grow these bromeliads outdoors; here in Vancouver, they are strictly indoor plants.

Desfontainia spinosa, a fine holly-leafed shrub with striking tubular red and yellow flowers, and Chilean guava (Ugni molinae), a charming pink and white flowered shrub, were quite common on the Tompkins’s ranch. Both were in Father’s collections.

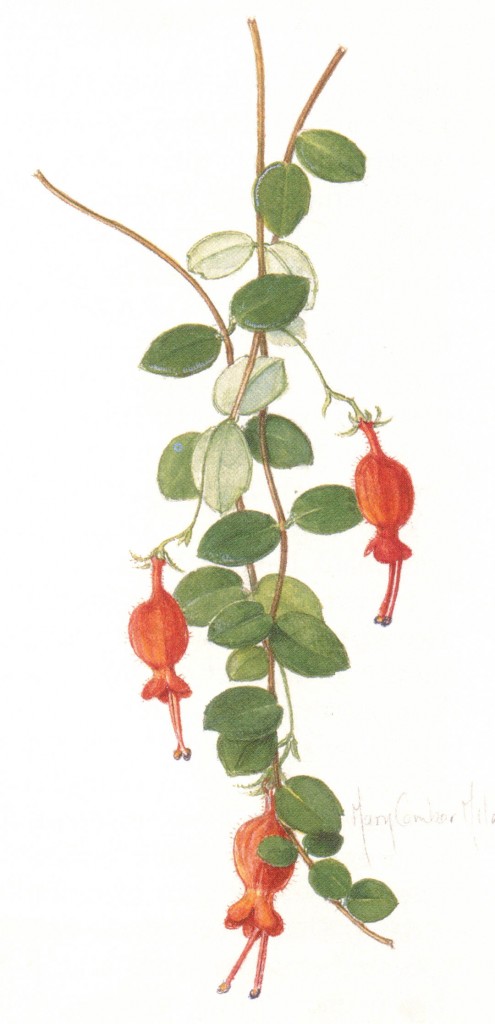

After a week of painting, I was taken to see more of the Parque Naturale Pumalin project that Doug Tompkins has instigated. It preserves 750,000 acres of forest containing almost unique stands of Fitzroya cupressoides—some a thousand years old. Privately owned but with public access, it is financially supported by El Bosque Pumalin Foundation (which has an office in San Francisco). Walking in to one of the awe-inspiring stands of fitzroya, I saw three red gesneriads growing as epiphytes ten feet above ground on a massive fitzroya trunk. These gems of the rainforest (Asteranthera ovata, Mitraria coccinea, and Sarmienta repens) were among the delectable plants I saw there that are semi-tender—or too-tender—for growing in Vancouver. Further south along the coast and in the Bay Area, these three should make more reliable shade-garden plants for the connoisseur, provided the humidity can be kept high in simulation of their rainforest habitat. Mitraria can be grown in gentle pockets in Vancouver, and I have seen it thriving in the South American section at Strybing Arboretum in San Francisco. On many childhood visits to Nymans, I was taken to see the asterantheras grown from Father’s seed and planted on the damp outside walls of the famous Walled Garden there; it persists there today and is prized. It was one of my first botanical painting subjects.

To further enhance my enchantment with that same fitzroya trunk, I gazed ten feet higher into the glorious bright pink bells of Philesia magellanica. This relative of Lapageria rosea is, to my knowledge, only grown by a handful of people in British Columbia. It seems to be more at home in Strybing Arboretum. We can be grateful that the magnificent trees and their delightful companions in Parque Naturale Pumalin will not end up as lumber or wood chips, destined for markets elsewhere.

In Argentina above Bariloche and San Martin de los Andes, seventy-five years after Father was there, I had the joy of seeing a plant representing the genus named for him, Combera paradoxa, as well as many of the choice alpine treasures that he collected. The rosulate violets—resembling sempervivums with circlets of viola flowers—and the beautiful Ranunculus semiverticillatus, which many alpine growers struggle to grow, were at my feet. These are plants for the alpine house, tolerant of cold winter temperatures, but languishing in the winter rains of the Pacific Coast. But what jewels they are!

On To Tasmania

November, 1999, saw me visiting some of Father’s collecting areas in Tasmania, where he had spent over six months in 1929-30 collecting seed and herbarium specimens. From the herbarium I was given a computer-generated list of almost three hundred specimens housed there, together with his collection dates and locations. This proved helpful in pinpointing his collection sites. The reaction of Dr Winifred Curtis, Dennis Morris, and other botanists there was that Father certainly managed to cover an extraordinary amount of territory in a country that at that time had few good roads and relatively little rail transport.

Ken and Lesley Gillanders, owners of Woodbank Nursery in Tasmania, met my plane in Hobart and drove me to their home for my first two nights. The loud dawn chorus of unfamiliar birds and the offer of Chilean guava jelly, made from her own bushes, for my breakfast toast, followed by a tour of their fascinating garden and nursery made for a perfect introduction to Tasmania. They grow successfully an enormous number of exotic plants and a selection of the finest of the local flora. I was intrigued to find in a damp, shaded cool house both sarmienta and asteranthera in flower, and philesia looking happy and healthy. Mitraria was in full flower, rampant as a climber outside.

In perfect condition in their garden was Diplarrhena latifolia—a fine large-flowered form of this iris relative that I immediately sat down to paint. The smaller flowered D. moraea is by far the more usual species; in the Hobart area, fields were white with it, responding as so many iridaceous and bulbous plants do to a recent fire. I’m sure the one I have illustrated could be a successful garden plant in the Bay Area.

Most appealing of the flowering shrubs were both pink and white selections of Anopterus glandulosus, called native laurel by Tasmanians, and Aristotelia peduncularis, which presents itself as an elegant shrub decorated with small, pendant white bells backed by soft green sepals and, later, with pink, purple, and white berries. I’ve seen the latter on roadsides responding to a recent clearing. I can see why Father hoped both shrubs would be hardy in Britain. They seem to be borderline in hardiness both here and there. I do not know of their cultivation in the Bay Area.

I was told that Tasmania has a higher percentage of berried plants in its flora than anywhere else in the world. In some cases the berries remain on the plants for a full year or more, often flowering and fruiting simultaneously. Members of the genus Cyathodes are fine examples from the epacrid family; birds and beasts are quite outnumbered by the fruits and might not select them as their first choice of food. I was pleased to encounter in the wild plants of Billardiera scandens—a climber and twiner with pale greenish-yellow bells, later producing spectacular shiny dark purple fruits.

[sidebar]

An Exhibit

Mary Comber Miles will have an exhibit of botanical paintings from her travels around the world, opening April 13, 2000, for three months in the Helen Crocker Russell Library at Strybing Arboretum. Notes on the plants will accompany each of the paintings.

Included in the exhibit will be a selection of plants painted on recent visits to South America, Tasmania, and South Africa, in addition to those from travels in Greece, Gozo (Malta), the French Pyrenees, Portugal, Italy, Thailand, and Java.

Sales of Mary’s paintings will benefit both the Library and the new Library Terrace Garden, built in memory of Mary’s close friend, Sally Heumann, a past president of the Strybing Arboretum Society, a chair of the library committee, and long-time volunteer at Strybing—and a patron of the arts.

The Library is open, free of admission, seven days a week, except major holidays, from 10 am to 4 pm. It is located inside the main gates of Strybing Arboretum at Lincoln Way and 9th Avenue, in Golden Gate Park. Call 415/661-1316 x 303 for more information.

[/sidebar]

Christmas carols were playing on the radio. It was late spring becoming early summer, and the Tasmanian Christmas bells—bold red and yellow Blandfordia punicea—that I had particularly wanted to paint were slow to flower at The Royal Tasmanian Botanic Garden where I was working. The staff, on weekends and evenings, was keeping an eye on wild populations for me. Imagine my delight finding hundreds in full flower near the south coast. My companion, with his collecting permit, was able to cut one stem for me. Father had suggested that this plant could have great potential in horticulture as a cut flower. Not much has been done with it yet; in fact, it seems to be the most challenging species of Blandfordia to cultivate.

A day on the slopes of Mt Field National Park was perfectly timed for me to see a coral-pink, small-leafed heath, Archeria comberi (also named for Father). It was in full flower in what I was told (and delighted to observe) was an extraordinarily floriferous year. A climb a little further up the slope put us amidst mountain pools and cushion plants of many different kinds, all new to me. A clear view west revealed tantalizing and, in most cases, almost impenetrable mountains—and perhaps more unidentified species.

My travels in South America and Tasmania, with their distinct floras, have been somewhat overwhelming, certainly enlightening, enriching, and moving. The lists of plants seen and identified seem endless. My desire for at least six lifetimes is perhaps normal for anyone sharing this field of interest.

Responses