Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Growing for Biodiversity

The Willamette Valley has a thriving export nursery industry. But most of that inventory is grown and bound for points east where cold winters and wet summers prevail. Plant those trees here in our mild winter, dry summer climate and the result is the drought-shocked urban canopy that can be seen around Portland and other western cities.

Other factors contributing to an ailing green infrastructure include the planting of canopy trees in greater numbers out of reach of irrigation, such as planting strips between sidewalk and street. Though our extensive “urban mulch” of pavement does help preserve ground moisture into the dry season, as historical sources of moisture—a hydroponic system of leaky clay sewer and water pipes—are replaced, questions follow like “why did most of the birch trees on my block just die?” And, whether due to a conservation ethos or ever-greater sticker shock at the water bill, many homeowners are cutting back on irrigation, thus, eliminating spill-over into adjacent areas. When planting trees in areas that are unlikely to receive reliable watering, think of trees that want summer drought. It makes life so much easier.

Oaks are the answer! Now that I’ve finally peeled the last election sticker off my car, maybe this is the next. What an amazing and vast group of trees. With about 600 species, many are not the typical eastern North American red oak.

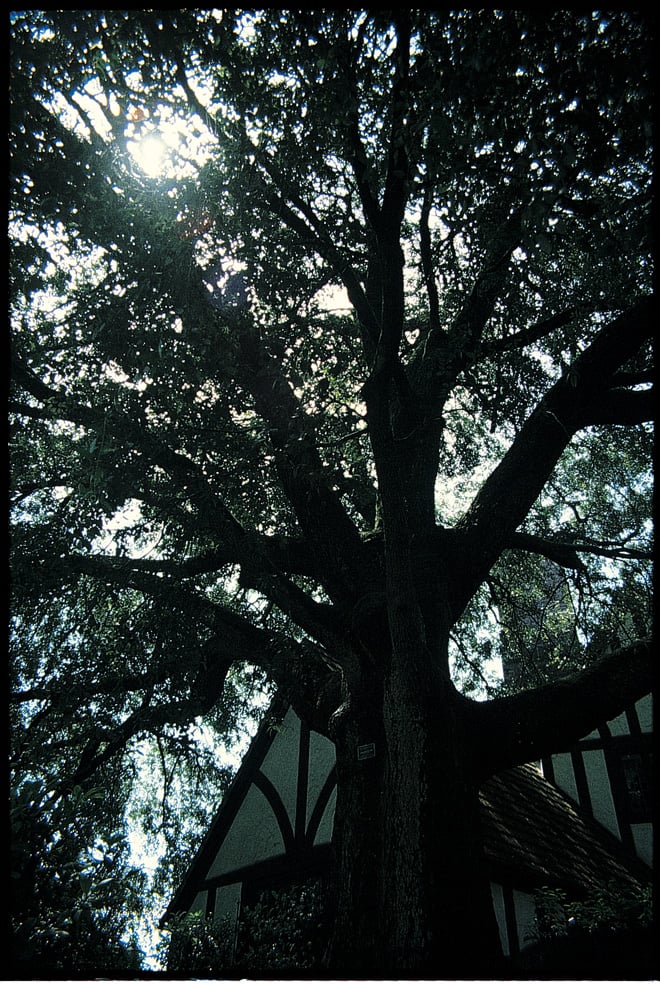

Oaks from periodic drought places are faring well in the urban environment. The evergreen Quercus ilex and Q. suber and the deciduous Q. frainetto from the Mediterranean have been around a long time, but many others are at our disposal. A favorite species with a long history in Portland is the canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis). Native from western Oregon to Baja and into mainland Mexico, their rocky habitats make them adapted to urban situations. Growth habit is a form-fitting upright vase, 30 to 50 feet or a bit more in time, and the undersides of the leaves and acorn receptacles often have a gold indumentum resulting in another common name, gold cup oak. As with other western oaks, they go through a period of spiny, divaricating growth as a browsing defense, so patience is required to obtain tree form.

Another useful western oak is the dwarf interior live oak (Q. wislizeni var. frutescens) found in foothill locations often adjacent to shrubbier species. With a multi-trunked habit and growth to less than 25 feet with silvery bark and dark evergreen leaves, this is a great candidate for smaller street or garden planting. Dwarf interior live oak has also proven easier to transplant than some of its kin; another plus. A personal favorite is the silver oak, Quercus hypoleucoides. My first acorn collections are now my street trees where they have grown to more than 50 feet in height in a little under 20 years—including a bit too much time spent languishing in small containers. Among numerous attributes they are deep-rooted with an upright form and have 3- to 5-inch, rather olive-like leaves with a downy covering on the underside making them seem to glow in angled light. Though still not the easiest species to find, silver oaks are on the Portland street tree list along with an ever-growing number of other species that are adapted to city growing conditions.

Also inhabiting northeast Mexico rain shadows is Quercus greggii. Originally thought to be a form of Quercus rugosa, we named a form from the mountains of Tamaulipas ‘La Siberia’ after a nearby town. In Portland, the stout trees have grown to about 25 feet with a rounded crown. With leathery leaves flocked with cream to tan fur beneath, the small trees appear much “lighter” than an evergreen might.

Another oak not really resembling what most think of one is the Japanese live oak, Quercus myrsinifolia. Though its East Asian origin might indicate a need for lots of summer water, it thrives with just a drink or two over the long, dry summer. Also deep-rooted, the smooth, gray bark and glossy, evergreen drip-tipped leaves set a lovely background for the burgundy-tinted new growth in mid spring. To about 30 to 50 feet eventually, I did find a 100-year-old specimen in Portland’s Dunthorpe neighborhood at over 90 feet. The willow oak, Quercus phellos, often residing in sandy soils of the southeast United States, is also slowly gaining popularity. To a possible 80 to 100 feet or more in time, the deciduous but late-dropping leaves often color well where we lack a good autumn display, and the fine texture with small acorns relieves ever-present mess and safety concerns.

From Crete, Acer sempervirens resembles a western live oak more than a maple. A little tree given to me as a seedling many years ago by Wayne Roderick is one that apparently fell into his pocket as a tiny seedling; it’s been in my repertoire ever since. The tree’s tough, evergreen leaves on stout branches form a dense canopy to about 20 to 25 feet. Sun and drought resistant, the leaves can briefly fall in early spring as new ones emerge, or with cold below 15 degrees F.

With the diversity of available plants that are adapted to our urban conditions, there is no reason every tree planted should be not be special, adapted to the site, a good fit for both scale and use, and beautiful. Rather than practicing punitive horticulture where we simply do without, or attempting to devise measures to grow trees ill-adapted to our climate, we should explore a more diverse palette of species that say, “bring it on!” to whatever our climate might throw at them. And plant a future where trees flourish and stand out as icons of a sense of place.

Prioritizing “Green Infrastructure”

Despite language to the contrary, often the green components of our cities are the last things preserved, and the first to be cut from the budget. Preserving historic plantings and providing ample space for new ones will be ever more important as our cities grow more dense. The following measures promote the health and longevity of trees in an urban environment:

Bury utilities wherever possible to avoid branches tangling with wires or lines that impede a maturing canopy.

Encourage the use of pavers set in sand near trees along sidewalks and roads so periodic adjustments can be made without the need to cut concrete and risk severing roots.

Eliminate root barriers that effectively cut off the availability of moisture from even the most water thrifty tree.

In our part of the world, the best-adapted, and might I add some of the coolest, trees are best planted from containers. Both

evergreen and deep-rooted drought-adapted plants resent bare root or ball and burlap transplanting.

Large specimens of many of the plants mentioned in this article are rare in our region, which means you’ll probably have to start small; besides, the selection is greater, establishment is often easier, and the joy of watching the tree grow will last that much longer. But be prepared to have a persuasive conversation with the local urban forestry permitting person if the planting is on the public right-of-way.

Responses