Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Garden Futurist

The author, in the Regional Oral History Office of the Bancroft Library, interviewed Lester Rowntree during the compilation of the Library’s document on her. Levenson has provided the Introduction to a new edition of Lester Rowntree’s Hardy Californians, just published by Peregrine Smith. This article is adopted from that introduction.

Hardy Californians is in paper covers and is available at bookstores or from Peregrine Smith, Inc., 1877 East Gentile Street, Layton, Utah, 84041. It costs $8.95 and, when ordered from the publisher, $0.75 for postage and packing.

Lester Rowntree started her career as an independent naturalist in her fifties and earned a modest but enduring fame for two pioneering books, Hardy Californians (1936) and Flowering Shrubs of California (1939). These small masterpieces, recording her observations of California’s native flora, are in the tradition established by the eighteenth century English naturalist and clergyman, Gilbert White. This tradition links close observation with love of the natural world. Lester described her methods in Flowering Shrubs:

I have approached the plants from the gardener’s, not the scientist’s standpoint, hoping that my account will bridge the too-wide-gap between botanical manuals and books on gardening…. In compiling it I have followed the invariable rule of writing only from my own notes, taken on the spot, of the things the plants have told me in personal interviews.

Lester’s enthusiasm, eye for detail, and talent for the mot juste shine through even the most detailed descriptive passages on the habits, needs, and qualities of California’s native flora.

Lester Rowntree was born Gertrude Ellen Lester in 1879, in Penrith, Cumberland, a Lake District town in northwest England. Nellie, as she was called in the family, was the seventh of eight children. The Lesters were an established Quaker family of a class known for their success in industry and commerce. Until 1828, Quakers and other nonconformists were barred from the universities and careers in government by the Test Acts. The Quakers turned their talents to commercial concerns, and three major Quaker families — Cadbury, Rowntree, and Fry — developed a virtual monopoly of the chocolate business in England. Quaker education stressed a pragmatic interest in natural history. Strict Quakers were forbidden most forms of entertainment and gardening became popular among them.

Edward Lester, Nellie’s father, was born in 1839, two years after Queen Victoria came to the throne. He made his livelihood as a tea merchant and grocer, but as his obituary said in 1910:

He was a man of scientific and refined tastes, while intellectually he was far beyond his contemporaries…. He was a man of many hobbies, a keen naturalist, botanist, and nature lover generally. Unfamiliar plants and mosses, little known insects, and all the native birds were known to him, and he was a wealthy mine of information on many out-of-the-way subjects calling for special research.

The obituary went on to describe Nellie’s eldest brother:

The love of gardening runs right through the Lester family…. Frank Lester is head of the Francis E. Lester Company, collectors and shippers of cacti, of Mesilla Park, New Mexico. The firm deals extensively in these queer plants and their price list includes all varieties from a potful of spiny marbles like Lilliputian hedgehogs to giant forms like telegraph poles, which are specially quoted by the foot.

This was the Frank Lester who later had a renowned nursery of historical roses in Carmel, and wrote My Friend, the Rose, in which he remembered his first garden in Cumberland:

Many years ago, there was a tiny plot of ground some four feet square in a little town of England’ s beautiful Lake District that, by wise parents, was set aside as soon as I could walk, as my first flower garden, the private domain of my earliest years, a place in which to play and work and adventure and imagine. From a bare spot of earth it grew to be a precious possession filled with hopes and joys and disappointments. As I look back on it today, that infinitessimal speck of the earth’s surface exercised on my life lasting influences utterly out of proportion to its diminutive size. It taught me many things in a manner far more lasting and efficient than any school-room ever succeeded in doing: patience and thoroughness, the trick of cooperating with Nature, and above all, the love of a garden.

Nellie received a similar garden at the age of two, and told of her disappointment when the bulbs planted upside down did not come up double as the coachman had promised.

In 1887, Edward Lester was persuaded to sell all his property and move with seven of his eight children to Galena, Kansas. According to Lester, her parents were taken in by a corrupt saleswoman who got a “rake-off” at each stage of the journey. The Lesters were promised a developed Quaker community with roads, schools, libraries, and colleges. But far from settled comfort, the reality was that there were no amenities and many families were still living in dugouts. Mrs. Lester started a school to which any child might come. Then tragedy struck. The Lester well became contaminated, the whole family sickened, and two of the children died. Lester said of this time, “Mother was a heroine, a heroine.”

The tragedy brought the Lester and Rowntree families, both living in Kansas, together for the first time. Mrs. Charlotte Rowntree read of little Howard Lester’s death and came with her children to pay a condolence call on the bereaved family. Nearly twenty years later, Nellie Lester and Bernard Rowntree met again and married.

In 1889 the Lesters abandoned their ranch and moved to another Quaker community in Altadena, California where Edward Lester took up fruit growing. Nellie was ten years old and her lifelong love affair with California wildflowers began.

Nellie’s schooling was interrupted a number of times. American public schools were not acceptable to Edward Lester. He said that American children never finished their meals at home (referring to their gum-chewing) and committed other gross improprieties — such as saying “ain’ t.” Nellie’s brother John was teaching at the Quaker-run Haverford College in Pennsylvania. The college president’s wife, Mrs. Frank Morley, needed a governess for her children. Nellie was sent for and spent at least two years looking after the three Morley boys.

Nellie had started a pressed flower collection and went as often as she could to study in John Bartram’s eighteenth-century garden, herbarium and library, near Philadelphia. Bartram, like Nellie Lester, had no formal scientific schooling. He established the first botanic garden in North America and corresponded with botanists including Linnaeus in Sweden and Collinson in England.

Nellie was sent to finish her schooling in a Quaker boarding school in Westtown, Pennsylvania. In English style, the girls were called by their last names. Nellie liked being called “Lester” (henceforth, she will be referred to as Lester). But she did not like the strict regime with prohibitions on singing, whistling, and roaming. She said, “I was so homesick — oh so homesick — but you know, I think home sickness is a good thing for anybody…. You’ve got to learn to stand on your own feet.” Lester graduated in 1902 at the age of 23. She apparently enjoyed the school, for she later enrolled her only child there.

Lester Rowntree said in her 100th year that to go to horticultural college would have spoiled everything because “All the originality would be gone. It would be all what you learned — put on, veneer, pretense. I don’t like pretense.” Still, when she had to give up the scholarship she had been awarded to the Horticultural College for Women in Ambler, Pennsylvania, in order to nurse her ailing mother, she must sometimes have resented her brothers’ freedom to continue their studies and pursue their interests. Hannah Lester died in 1907, five years after Lester had graduated from high school. Then her father said, “Now you can’t leave me.” And Lester did not.

Years later Lester told a friend, “I was brought up to be a Victorian daughter, to help Mother serve tea, to arrange flowers, and then to marry.” After her mother’s death, Lester and her father went to live at Haverford with John. Lester pressed flowers to add to her collection, studied voice, and endured what she perceived as the claustrophobic atmosphere of the small college town. In 1908, at the age of thirty-one, Lester chose Bernard Rowntree from among her suitors and married him, nearly twenty years after their first meeting as children in Galena, Kansas.

Bernard Rowntree was an engineer with the Otis Elevator Company in New York and was a member of the Rowntrees, a prominent English family of chocolate manufacturers. He seemed to dote on his pretty and vivacious bride. The couple built a comfortable and capacious house in Oradell, New Jersey. The bride’s father lived with them until his death in 1910. In 1911 the couple’s only child, Cedric, was born.

Lester designed her first garden in the conventional idiom of the period: two rowan trees at the gates to commemorate the name Rowntree, a fine lawn, rock garden, herbaceous perennial border, a separate vegetable garden, and below that a chicken yard. To help her in the garden Lester had an Italian gardener, her husband, and her father. The size of the house and the period suggest that there was some household staff as well.

However, this was not an entirely conventional New Jersey suburban household. Every weekday morning Lester jogged with her husband to the commuter train, then home again, for exercise. She was known as the “running bride.” She claimed to be the first woman in New Jersey to wear trousers. Lester was pursuing her botanical interests as actively as she could and did some seed testing for government inspection bureaus. She corresponded with horticulturalists around the world, exchanging seeds and observations. During her marriage she started a remarkable seed catalogue collection which was later donated to the California Academy of Sciences. Once a week she opened her garden to the public while she remained closeted indoors.

Health problems concerned Lester when she was in her forties. She had a hysterectomy and believed she would shortly die of cancer. Bernard Rowntree gave up his career and granted her “dying wish” to move to California so that she could die amongst her beloved wild flowers. The Rowntrees moved first to southern California, then to a fine house in Carmel with stables for Cedric’s pony.

Despite the couple’s efforts, the marriage of more than twenty years foundered. In 1932 Lester paid fifteen dollars for the divorce. At the end of her life, quite unprompted, she said:

I wasn’t fair to my husband. I’ve always wanted to apologize to him…. I think I’m rigid. Physically, I didn’t give enough — I’m not sexy enough.

Suddenly, in her fifty-third year, the natural world had opened up for Lester Rowntree. In 1939, she wrote:

It took adversity to bring me the sort of life I had always longed for. Not until after my domestic happiness had gone to smash did I realize that I was free to trek up and down the long state of California, to satisfy my insistent curiosity about plants, to find them in their homes meeting their days and seasons, to write down their tricks and manners in my notebook, to photograph their flowers, to collect their seeds, to bring home seedlings in cans just emptied of tomato juice.

For the next twenty years or so, Lester’s life followed a fairly consistent pattern. Her yearly routine would revolve around wildflower seasons: beginning in March on the Southern California deserts, moving to the seacoast, the foothills, and culminating in July and August in the High Sierra. She would return to Carmel for the winter spending her time reading, writing, listening to music, and sorting and packaging seed which she sold under her own label. Her major publishing outlet at this time was the Santa Barbara Gardener, to which she contributed thirty-five articles between 1925 and 1942. In the pages of this journal and many other publications her two books were early and enthusiastically reviewed.

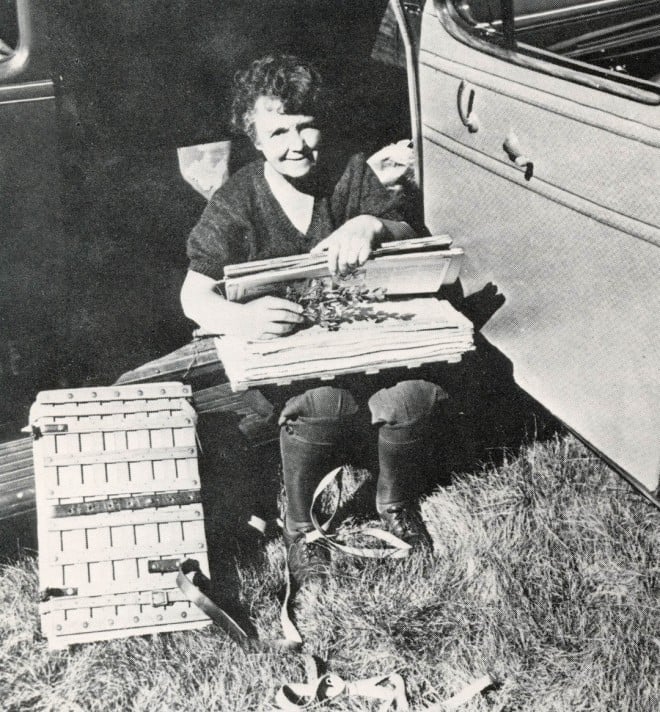

Lester usually traveled alone in a car which she converted into an efficient camping wagon by removing the back seat and outfitting the space with supplies. Leaving the car, she would reach remote places on foot and, when necessary, with a pack animal. Every region of California — desert to redwood forest, sea coast to mountain peak — was explored and recorded in notes, photographs, collected specimens and seeds.

Lester’s hillside garden in Carmel Highlands became world famous. It was the antithesis of her formal garden in New Jersey. Only California natives, or as she put it, plants that behaved like natives, were allowed. Plants that behaved like natives were those that came from areas with climates similar to that of California, did not take over the garden, and did not require a lot of extra care. She stocked the garden with plants she collected, bought, or exchanged with other horticulturists, and occasionally stole for the purpose of conservation. James Roof once asked her how she had acquired the Laurel Hill Cemetery manzanita. She answered, “I garnered it ghoulishly in a gunnysack.”

Lester did some work as a landscape architect. She advertised her specialties as “intimate gardens, rock gardens, wild flower gardens.” She also described herself as a maker of gardens which express the owner’s personal tastes and as one who carries them out with beautiful and unusual plants, exotic or native. She designed a rock garden for the Santa Maria Inn, a fashionable resting place for motorists traveling between San Francisco and Los Angeles. It is unlikely that Lester made much money from this aspect of her career.

Financially on her own from 1932, Lester recalled sometimes living for ten cents a day on chicken feed boiled and eaten like oatmeal. However she did publish over a hundred articles during this period and was probably not so poor as she made herself out to be. Gathering materials for her writing, she took long trips not only in California and most of the rest of the United States, but in parts of Canada and Mexico as well. However, it was the above-timberline Sierra peaks which were her favorite places. As she wrote of them in Hardy Californians: “These are the heights which no machine except the human body can climb. These summits are above the destructive potentialities of real estate agents, or even of sheep or cattle. There is a glorious feeling of remoteness and permanence here.”

On some of her botanizing tours, Lester claimed that she would run out of money, have to drop down from the mountains, and “throw a talk” to a garden club or school. She was, in most professional respects, very well-organized. In a letter to a friend written in 1971, she said:

1940 was fun! I never slept in a motor court or hotel the whole year. I had two cartons in the back of the car — one containing gypsy clothes and a suitcase of lady clothes. One night on the blessed ground and the next (where I had to throw a talk) in a stuffy, cushioned, curtained room, with a maid to ‘draw my bath’ as well as my curtains.

Lester Rowntree was not a successful businesswoman. The seed business, Lester Rowntree & Co., never made money. The “& Co.” consisted of a school friend, Lila Clevenger, who was left behind while Lester toured and talked. Eventually Miss Clevenger, for whatever reasons, accepted orders for seeds but did not fill them. The matter ended in the courts.

Lester sometimes portrayed herself as a backwoods eccentric. She did need solitude and open spaces, but she also needed good company, and comforts too. In her article “Lone Hunter” in the Atlantic Monthly, she wrote: “One of the trials of my life is the difficulty of combining the arrangements of a lady with those of a gypsy. I don’t want to give up either sort of existence.” Alternating between the wilderness life and the comforts of Carmel, Lester struck her own balance, proving that she could enjoy both wilderness experiences and domestic comforts. She confessed in one article:

Back in the man-made world I am, for a time, filled with nostalgia for high places that I had made my own. I chafe at the confines of walls and ceilings. I made adjustments, but I keep trying to recapture that fading fairy tale of the free life among rocks and plants and wild creatures. As I settle down, relearning how to live the well-rounded life, I begin to perceive that the tame, as well as the wild, has its place when it comes to collecting myself.

The 1950s were difficult for Lester. She had planned three books on California flowers, shrubs, and trees. The first two were written and published. She was working on the third in her “working shed” above the Carmel house where she kept all her notes and photographs. The shed burnt down. Some said that the fire was caused by a defective kerosene heater. Lester’s daughter-in-law, Harriette, thought it arson; a fire set by a Filipino man who was sorry for Lester’s former partner, now antagonist, Lila Clevenger. In any case, Lester was disheartened and did not succeed in publishing her other book-length horticultural manuscripts, which can be found in the Rowntree Archive in the California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco.

Now, in her seventies, Lester’s eyesight began to fail, making the camping trips harder and less rewarding. Lester turned her skills to writing children’s books and published four of them. She described the books as potboilers, written only because she needed the money. All have merit, however, and Denny and the Indian Magic achieved a local following in the Big Sur-Monterey area during the sixties.

In her eighties, Lester enjoyed a late spring. Two grandsons earned their doctorates in Geography, married, and raised families. With those of her granddaughter, Lester now had eight great-grandchildren whom she much enjoyed. She also had more time to garden. Depression could be managed by playing “that game of put and take we call ‘gardening.’ I would go out for only a few minutes, but it would be dark when I got back into the house.” She enjoyed listening to music on her radio, kept permanently tuned to KPFA, Berkeley’s somewhat radical F.M. station.

Finally, in her nineties, Lester could no longer safely live alone. She fell with some frequency, and her eyesight was rapidly deteriorating. Cedric and Harriette, son and daughter-in-law, with Lester’s grudging consent, enlarged the Carmel house to make separate apartments for the families. Harriette helped Lester free herself from dependence on barbiturates. A doctor had prescribed sleeping pills to Lester with her nervousness when she had to make a public talk, and eventually their use became habitual.

Two months before her death, Lester had to be moved to a Carmel convalescent home. She did not die on her beloved hillside as she had hoped. But a group of friends took her back home one day in January, 1979. She enjoyed her tea, the wonderful scents of the chaparral, and the bird song.

Lester’s formal schooling ended with high school, but for her, education was a lifelong process. Professional recognition for her achievements finally arrived. Her formal honors in the worlds of horticulture and conservation included election as Honorary Secretary of the British Alpine Garden Society, Honorary Life President of the California Native Plant Society and President-at-large of the American Herb Society. She received a national award from the American Horticultural Society which cited Lester for the “conservation and propagation of California’s flora, famous as author, photographer, and lecturer and children’s author. A truly great personality of horticulture.”

Lester Rowntree, did what she wanted to do, at least after the age of fifty. She once said: “Don’t get me wrong; I believe in women’s liberation. I just feel if you want liberation — take it! If you want to do something, just get up on your hind legs and do it.” She described herself as a ‘lone hunter,” but she had hosts of friends. She was no ascetic for the sake of asceticism. Lester had a richly cultivated mind and read extensively. Her fine and apparently spontaneous writing style was meticulously crafted.

One of her favorite quotations was, “Hell itself will yield to industry.” Whatever private hells she lived through, her public life can be a model to men and women alike who have a dream. They too, at any age, can “get up on their hind legs, and do it!”

Lester Rowntree’s life at the end, quietly and gradually ebbed. She died on February 21, 1979, in Carmel, California, five days after her hundredth birthday.

Responses