Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Plants You Need, Sustainable Gardening

I recall one July evening with Canon Boscawen. When he looked up at his great tree of Metrosideros robustus, some forty-five feet high, against its background of dark pines, evening light was adding a fiery glow to the vermilion on the sunny side of the mass of flowers… l like to think that that grand old man of Cornish gardening, who for forty-seven years replenished the well spring of his life in cultivating Ludgvan garden, had the happiness of seeing his old tree in such glory before it was struck down by frost, and he by paralysis.

W Arnold-Foster, Shrubs for the Milder Counties

The art of landscaping and the art of painting are closely allied, and at times they have been intimately connected. The anomalies of perspective and proportion seen in Chinese gardens — the miniaturized hills traversed by mouse-track paths, for example — were a deliberate imitation not of nature but of classical Chinese scrolls. In England the great eighteenth-century landscapes of William Kent, Henry Hoare, Capability Brown, and others were consciously influenced by the paintings of Poussin, Claude, and Ruydael. The landscape shapes of Burle Marx or Thomas Church have often been compared with abstract painting, and Monet’s garden at Giverny (Pacific Horticulture Summer ‘85) was planned almost as a sourcebook and stimulus for his later paintings.

It is, of course, futile to compare different arts (is architecture “frozen music?”), but it is of some interest and certainly of great practical importance to remind ourselves that, if gardens are pictures, they are pictures that change over time. This is a matter of degree. The eighteenth-century landscape gardens, because of their scale, changed little with the growth of plants. But aside from man’s intervention (as in the controversial rhododendrons later planted by the lake at Stourhead), change is intrinsic to the life of the garden. The great beeches die, and the stone crumbles. James Russell, at one time manager with Graham Thomas of Sunningdale Nurseries, spoke years ago in San Francisco on the expensive and intricate problems of restoring old gardens to their former “unchanged” state. If gardens are akin to paintings — or to sculpture, since they involve different angles of viewing — they also share elements of the temporal arts such as music, drama, and novels.

The grand landscapes change little, as they are intended to do. The modern small architectural garden, such as the Donnell garden of Tommy Church (in Napa Valley, California), is affected only by the gradual decay of wood, cracking of concrete, or ultimate death of the native oaks. David Sheppard, who maintained the Donnell garden for some time, told me that gardening practices there were aimed precisely at eliminating any suggestion of change. The lawns, for example, were cut with rounded verges so as to look, as much as possible, untouched. The static quality is intrinsic to the design.

Where time must be taken into consideration is where a wide variety of plants, and especially little known plants, are grown — in short, in the plantsman’s garden and in the arboretum, public or private. Sometimes change is anticipated, as in the Westonbirt Arboretum in Gloucestershire, England, where the Holford family, aided by immense riches and acreage, also had the skill, over generations, to plant with the ultimate size and shape of the trees in mind so that, for the most part, the rides today retain the proportions and spacings intended by the founder. The original plantings of the Strybing Arboretum in San Francisco, on the other hand, needed renovation after less than fifty years because Eric Walther, possessed by unbounded vision but hampered by lack of money and space, planted whatever and wherever he could. The future, as it does, caught up with the arboretum, resulting in a magical but confused jungle of mossy trunks and overhead foliage in which the distinctiveness of the trees was often lost. In recent years Strybing staff and friends have been engaged in the fascinating but costly task of correcting the ravages of time.

I have been, for a good part of my later life, an impenitent plant collector. I have had, however, the good fortune of a partner and friend with a judicious and practical eye for the ultimate habit and growth of plants and their placement, and who thus provided a home for our acquisitions in what occasionally seemed to us a successful garden. Now I have to plan and plant, to think of foliage masses, views, and vantage points — in short, to become a gardener myself. Necessarily this involves stepping back to view in general terms our project of twenty-five years and, in some of the conclusions reached, I have surprised myself.

Since we are concerned here with movements and revolutions in time, the image of the garden as a sort of giant clockwork comes to mind, with the large wheels (trees and shrubs) revolving slowly over a period of decades, the smaller gears (shorter lived woody plants) revolving over years, and the smallest (perennials and reseeding annuals) whirling about it in months or weeks.

Trees and Shrubs

First, the large trees, the slow-growing basic structural elements of the garden. Here the years have brought quite unpredictable changes in size and form. Eucalyptus nicholii, for example, we first saw as a medium-sized tree in Max Watson’s pioneer eucalyptus plantings in San Jose. He generously gave us seed, from which our trees were grown. Unfortunately, we did not note in Blakely’s Key to the Eucalypts, our bible of the time, that they might grow to one hundred feet, which they apparently intend to do, with the attendant danger of wind damage and uprooting in our climate. On the other hand, Acer griseum, the paperbark maple, which we were told would reach forty-five feet, has achieved less than twenty in as many years, perhaps from poor siting, and never has had enough girth of trunk to display the shiny peeling bark. Moreover, it resents our heavy winter rains, and two died from excessive dampness a few years ago. Gymnocladus dioica, the Kentucky coffee tree, which Bean describes as “in its foliage perhaps the most beautiful of all hardy trees,” showed its dislike for our climate by remaining spindly and sparse for over twenty years.

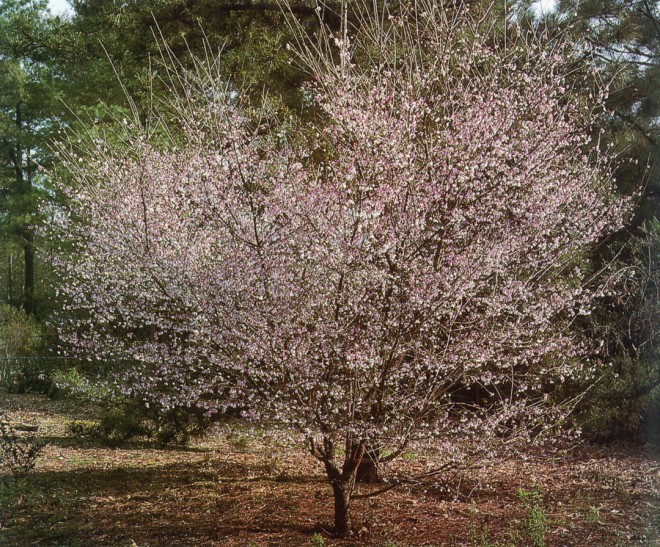

The years have brought changes, some good and some bad, to the form and structure, as well as the size, of the trees. The Serbian spruces, Picea omorika, lived up to all expectations and became graceful spires. But Abies grandis, aside from excessive growth, and A. mariesii have developed no personalty of their own. The cypress pines (Callitris species), dowdy when young, have developed weeping branch tips with the years and promise to be beautiful adjuncts to the garden. Such a common tree as Zelkova serrata, originally planted in a close group of five as a substitute for the unobtainable Z. carpinifolia, with the intention of instantly imitating the great Wardour Castle tree pictured in Bean’s Trees and Shrubs, and now reduced to one survivor, has finally developed its own beautiful vase shape and probably will not be removed. Ornamental cherries we planted in quantity but found their drab foliage unsatisfactory on a year-round basis. We removed all but the largest (Prunus sargentii) and the smallest (P. incisa) of the Japanese species.

Shorter Lived Woody Plants

The years have brought the same unexpected developments of growth and form in the faster moving circle of shrubs. Two fine hybrid grevilleas, ‘Poorinda Constance’ and ‘Canberra’, have become far too large, creating a twenty-foot-high jungle and refuge for rabbits; they will be removed. Two other shrubs, Xanthoceras sorbifolium and Decaisnea fargesii, planted with high hopes, never appreciated their siting, and remain a challenge.

Aside from size, the developing structure of shrubs has also produced some surprises, pleasant and unpleasant. Genista tenera, tolerated as a curiosity since it looked remarkably like the pernicious Cytisus monspessulanus but with woolly seed pods, grew after some years into a fine pendulous shrub, commented upon by many visitors to the garden. Acacia podalyriifolia, with its beautiful pearl-gray foliage and pleasant habit of blooming in mid-winter, became, in its second planting (the first froze in the dreadful winter of 1972) a lanky, uninteresting shrub.

The rock roses, Cistus and Halimium species, present special problems, and I have reversed my opinion about their utility, at least in this garden. I have always been interested in the two genera and their hybrids, but time and our climate have forced reconsideration. When friends and I visited the University Arboretum at Davis and were shown the Mediterranean garden there, I was struck by the superiority of the plants (rosemaries and lavenders as well as rock roses) to my own. Of course, these plants were young, and they are rather short-lived in California gardens. But I realized also that the heavier rains and greater shade in our garden militated against the compact growth of these plants. In our garden Cistus x skanbergii, C. crispus, and C. x Iusitanicus ‘Decumbens’, properly low, spreading plants, climb into the shrubbery and become lax and loose. Ironically, through Lester’s writings, our garden has become identified with Mediterranean plants and doubtless will remain so in part. But the years have forced a major rethinking of these plantings and the removal of large areas of rock roses in favor of plants requiring less sun.

Annuals and Perennials

Turning now to the smallest whirling gears in my clockwork image, the perennials and annuals, I find myself again contemplating a major change in direction. Perennials have always been of great interest to me, and were a main interest of Roger Warner, who collaborated with us for some time on the garden and nursery. Through seed lists, friends, and the importation of cultivars, we probably amassed as large a collection as any in the country.

The problem is that I really don’t know what to do with them, and I think that no one else, especially on the Pacific Coast, does either. We have books to guide us, but these are, for the most part, either English or based upon the English tradition of the seasonal perennial border. With our peculiar rainfall patterns, and lacking the silence and snowfalls of winter, we have to invent our own procedures. This might be, and probably should be, a challenge rather than a source of discouragement. Certainly a great deal of knowledge about suitable plants and suitable situations for plants is being amassed by ingenious gardeners in the West.

I still must admit to a certain ambivalence towards the currently popular notion of the perennial border. At once I have the deepest admiration for the extraordinary achievements of Miss Schwerdt and Miss Kreutzberger, recently retired from Sissinghurst, in managing a garden of felicitous color relationships and pleasing shapes from spring to early fall. Nonetheless, aside from lack of time and talent, I hesitate to embark upon this extremely exacting kind of gardening. Since this is a somewhat controversial point, I shall blame it on my own idiosyncrasy: for me, plants trail their meanings behind them, and an appreciation of meanings takes time both for the gardener and the beholder. The display garden, to me, is too rapid and too impersonal a production to compete for my interest with the slower parts of the garden. After all, how many meanings does a coreopsis have to trail?

Trailed Meanings

On the subject of meanings, a small digression may be worthwhile. Nature, aside from being a vague concept, is a step-child of the common sense and philosophy of each historical period. For the Romans nature was full of portents and auguries, for the medieval Christian world it was evidence of God’s (or the devil’s) order. For the modern scientific world, beginning, say, with Hume’s “sense data” and extending through Bertrand Russell’s mathematical logic to the triumph of the computer, nature has become an anemic and empty notion, reduced to a mass of data that are associated or structured to approximate the world of things, activities, and people in which we make our home.

In gardening terms I think there is an unfortunate tendency to reduce the art of horticulture to matters of color, texture, and shape, and to reduce the plants to the interchangeable “plant materials” or “growies” of landscape architecture classes. In commercial or amenity gardening this is not of much consequence, as is true also, I think, of display gardens such as Sissinghurst. It is quite a different matter in the plantsman’s garden.

For the plantsman, and this is perhaps how we define him, the interest of the plant is not exhausted by its color, size, shape, or botanical definition. The plant is “funded,” in Dewey’s words, with meanings. It is not indifferent that pulmonarias are called lungworts, that oaks were sacred to the Druids, that Laurus nobilis crowned heroes as well as flavored stews, that Franklinia and Berberidopsis are extinct in the wild, or that Metasequoia is a living fossil.

One of the more subtle aspects of gardening is the coordination of meanings, as, for example, in the all-native garden, the Mediterranean garden, the woodland garden, the old rose garden, or the garden that echoes historical models. For the gardener these connotations can be quite private, down to the lily grown because dear old Aunt Jessie cultivated it back home. The garden hums or crackles with discordant or harmonious meanings. When planning our own garden, Lester Hawkins remarked that the problem was “convincing plants to lie down together.” I believe he was not thinking exclusively in spatial or visual terms.

Disregard of meaning is often associated with idolization of technical achievement. It is, perhaps, advancing age that makes me view the garden as a refuge from techniques rather than a place to display them. It is difficult to picture Gertrude Jekyll, with her shawls and bad vision, sitting down to a computer terminal to plan her borders. Nonetheless, the intricate plantings and timed substitutions — the gypsophila ultimately to be pulled over the fading oriental poppies, and so on — outlined in Color in the Garden seem to foreshadow a world of technical achievement rather than an older one of art. This is analogous to the present-day proliferation of musical virtuosity at a time of the virtual death of significant composition.

Old Age

As I began this essay, I was uncertain whether I would be considering the aging of the garden or that of the gardener. The bite of time is more painful to some gardens than to others, but it is uniformly fatal to us. How are we to regard the interplay, the syncopation, between the movement and life of the garden and of the gardener? Gardening is a costly and time-consuming activity, and the garden is a temporary work of art. The emotional effect of the garden derives precisely from this poignancy, akin to that of seeing dancers or hearing singers and knowing they will not be tomorrow what they are today.

In a novel by Edward Hyams the protagonist returns to public life after a sojourn in his father’s garden because activity in the “corridors of power” is an antidote to the transfixed and unmoving world of the garden, which he finds life-shortening in its effect upon one’s sense of the passage of time. If I had access to power and public places and were convinced of the morality and efficacy of such power, would my life or sense of life be lengthened by leaving the “timeless” garden? I think not. My garden, and the other gardens I know, are not static or timeless, but echo our own human fragility and mortality with a fragility and mortality of their own.

One of our earliest gardening friends was Donald Stryker, the Oregon plantsman, and we visited his garden at Langlois before starting our own. After his death we visited his garden again, at that time looked after by a neighbor. The smaller treasures, such as the daphnes and Slieve Donard dieramas, had already succumbed to weeds, and the suckering clump of Philesia magellanica had been abducted by unscrupulous visitors. But the mist system in the greenhouse was still operating, and Stryker’s camellia cuttings had rooted in their boxes. In its larger aspects — the fine golden oaks, the Loderi rhododendrons, the Himalayan magnolias — the garden was still splendid. This was my first recognition of the close connection between garden and gardener, and the experience has never lost its emotional impact.

The gardener’s life is not shortened by the garden because the garden is not a timeless paradise but as vulnerable and mortal as ourselves. The answer probably is not to be found in philosophical reflection but in weeding and watering. There is so much to be done, so much to anticipate. Long before his final illness, Lester Hawkins wrote the briefest and most apposite epitaph for himself and other gardeners: “Gardeners always have something to look forward to.” On the final day, alas, this will still be true.

[When Marshall Olbrich died in 1991, this article was awaiting final correction. It appears now with the approval of his brother and the present proprietors of Western Hills Nursery.]

Responses