Contributor

- Topics: Archive, Drought and Fire Resilience

Although late in the series, this article is in the nature of an introduction to the author’s contributions on gardening with Mediterranean plants. Comparison of our own with regions of similar climate throughout the world helps in the cultivation of their plants. The series will continue in a future issue with an examination of the garden possibilities of flowering shrubs from Western Australia.

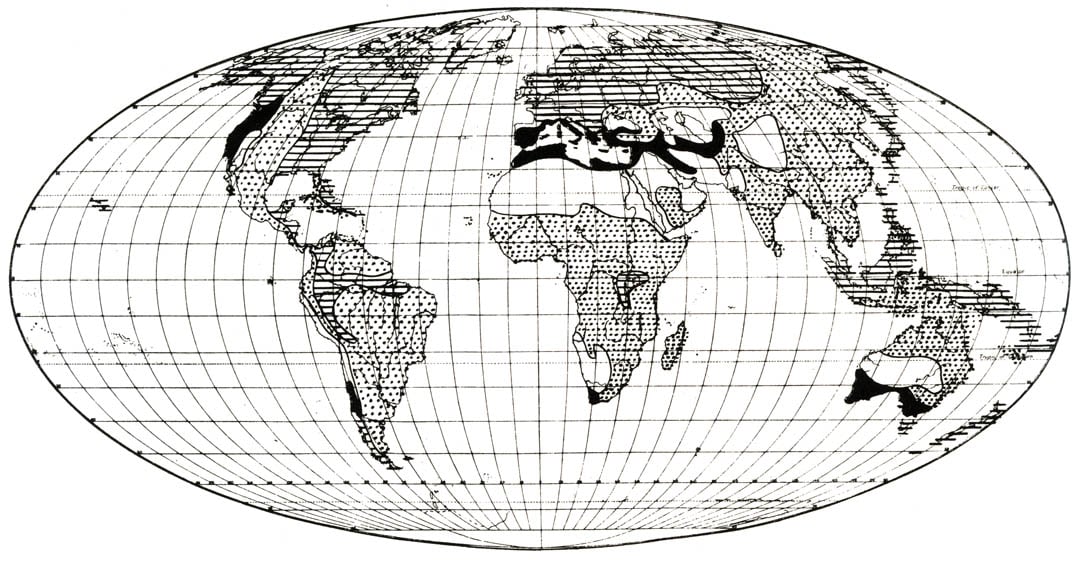

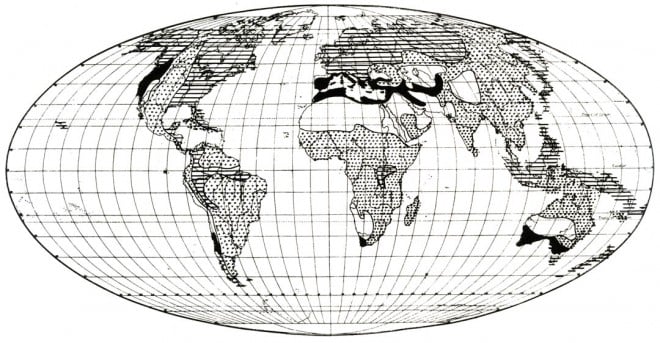

On the west coasts of all the great land masses of the world and on the warmer sides of the temperate regions (those that are farthest from the poles) lie those sunny lands that nevertheless are not deserts, but, instead, support rich and remarkable floras. There are five such areas of Mediterranean climate: the land bordering the Mediterranean on all sides, our own Pacific slopes, central Chile, southwestern and southern Australia and a small western portion of the Cape of Good Hope in Southern Africa. In the northern hemisphere, these areas are roughly centered around 40° latitude and in the southern hemisphere around 35°, an important difference, as we shall see.

No two climates of the world are exactly alike, yet all these regions have much in common. First and foremost, these are, in the usual shorthand phrase, the winter-wet, summer-dry parts (it is a phrase, however, that needs a little spelling out). As we have seen, all the Mediterranean climate zones are located on west coasts and the prevailing winds of the world are westerly, therefore these are all, in varying degrees, maritime climates where continental temperature extremes are rare. Thus we can say that these are areas with a cool season and a warm season, where sufficient rain falls to maintain a varied and often dense plant life and where it falls mostly in the cool season. The warm seasons are more or less extensive periods of drought with very little rain or none at all; they are sometimes hot but are more often tempered by the westerly winds from the sea.

Many consequences follow from these facts and they are felt in all our areas. The most important for us here is that in all these lands spring is a time of an onrush of growth among native plants that later must endure drought, sometimes prolonged, with the corollary that the plants that survive this ordeal possess the means for doing so. This necessity gives rise to many of the characteristic features of Mediterranean plants, features that we gardeners often find so attractive, such as the nearly leafless green stems of brooms, or the grey-green or glaucous coloration of many shrubs, or, as in our manzanitas, the ability of some shrubs to lose leaves in summer and thereby exhibit handsome trunk and branch patterns. It is also worth noting that late in the dry season all our areas are threatened with fire. Spring plant growth becomes a potentially combustible mass as transpiration falls to a minimum and atmospheric humidity sometimes drops to near-desert lows. The ability to resprout after fires is a feature of many of the plants we shall be considering.

It goes without saying that so far I have been describing a median climate for the areas with which we are concerned; as we approach their edges, the situation, as we might expect, is less clear. On the poleward side, where there is land Mediterranean zones give way to areas of year around rainfall (France, Austria, the Balkans, British Columbia, southern Chile). On the equatorial side the period of drought becomes longer and more extreme, finally ending in deserts (the Sahara, Baja California, Namaqualand, the Kimberley, the Atacama). These gradual climate changes are particularly important to us on the Pacific Coast, because our winter rainfall area has the greatest north-south extent of any in the world. Also, as we all know, climates have a way of not keeping to absolutely regular schedules, and the borders of our Mediterranean regions are continually shifting, sometimes to bring winter rain to the deserts, sometimes to bring drought to the north (recently in Europe as far north as England). Nevertheless, it is possible to establish a fairly definite demarcation by taking averages over an arbitrary period of time, say fifty years, or by defining an area as Mediterranean if it has the characteristics we have described for twenty-five years, say, out of thirty.

And, of course, all five of our regions differ from each other in ways only slightly less marked than the features they have in common. Here, the direction, height and location of mountain ranges play the leading role. The mountains around the Mediterranean basin are latitudinally arranged (extend east and west); the basin can be considered therefore as a vast funnel for the west winds and the sea itself a carrier inland of Atlantic ocean influence. This great extension of a typical west-coast climate far into the great continental land mass formed by Europe, Asia and Africa is unique in the world and it continues the winter rainfall pattern almost to the heart of Asia. As we might expect, continental influence, in the form of greater temperature differentials, increases as we travel eastward, and the climate of the heartland of Asia Minor is a mixture of Mediterranean and continental characteristics. Here plants must not only endure drought and heat but intense cold as well; this is the area richest of all in plants with bulbs.

By contrast, in our Pacific Coast region the mountains are longitudinally arranged (extend north and south) and are not far from the sea, two facts that give us a longer and less-deep winter rainfall area. As the traveler proceeds down the coast from the Canadian to the Mexican borders of the United States he finds that the summer dry season gradually lengthens but that winter rains remain the rule throughout. Thus, we can say that Southern California has an extreme Mediterranean climate with an admixture of desert zones. Western Washington, on the other hand, appears so green to summer tourists from California that they often think they are in a totally different climate, but this is still a summer-dry area as anyone who tried a garden of vegetables on the Tacoma prairie without irrigation would soon discover. The annual rainfall of Seattle is thirty-five inches, of which only five inches falls from frost to frost in the warm season. Because of this vast extension of our winter rainfall area to the north, some authors have put western Washington and Oregon into a special class — the winter storm belt. I see no reason for this distinction however, and would prefer to say that this is the coldest of all our Mediterranean climate areas, just as parts of Western Australia are the warmest.

All three of the winter rainfall areas of the southern hemisphere also have their distinct peculiarities. The smallest of all our regions is the western side of Cape Province in Southern Africa. The limited extent of this area is the result of abruptly rising mountains near the sea and the fact that the continent of Africa breaks off at 33° latitude (San Diego lies just below 33°). (For its size, however, this is one of the richest floral provinces in the world; in approximately 150 square miles there are nearly 2,500 species of plants.) Our next smallest area is central Chile. Here the mountains extend north and south as on our Pacific Coast, but they are even closer to the sea. Also, for complex reasons mostly connected with the narrowness of the lower reaches of the South American continent, the year-round rainfall part of Chile extends farther northward than similar areas in our hemisphere do to the south. In Australia it is the absence of mountains and the shape of the continent presenting, as it does, a long front to the west winds that gives this Mediterranean climate area its depth. Here, however, as you go eastward toward Melbourne you find the climate gradually changing to an east coast one of year-round rainfall and you see damp woods and tree-fern gulleys. Like western Washington, although in a different sense, southern Victoria is a borderline case.

Mountains are also important locally, perhaps nowhere more so than in a Mediterranean climate area where they determine the amount of maritime influence and protection from north winds a given microclimate will receive. As winter storms strike the coast of California, they encounter first the comparatively low coast ranges and later the Sierra Nevada, but even the hills near San Francisco Bay have an extraordinary effect on rainfall patterns. The west side of Mt. St. Helena, seventy miles to the north, has an annual rainfall of nearly ninety-five inches. Occidental averages fifty-six and a half inches, Kentfield near Mt. Tamalpais (and only ten miles from San Francisco) forty-six inches, San Francisco itself twenty-three inches, its suburb San Jose thirteen inches, and Walnut Creek, another suburb, nineteen inches. In summer, Walnut Creek will often experience temperatures of 100° while only about fifteen miles away, the thermometer in Berkeley is in the sixties. This pattern is reversed on cold nights in winter when Walnut Creek can receive fourteen degrees of frost while temperatures in Berkeley are well above freezing.

I have said that Mediterranean regions are mild climate areas and it is true that they have been widely celebrated by poets and talked about by laymen as genial lands, but it is a statement that also needs qualification. In this respect, there are two very marked differences between the winter rainfall areas of the northern and southern hemispheres. One, which I noted earlier, is that the latter are all a few degrees closer to the equator than their counterparts in the north. More important, however, is the fact that the southern regions are more extensively exposed to ocean influences. Southwestern and southern Australia and the Cape Province are bounded on the poleward side by the Southern Ocean, and central Chile has only a very narrow land mass lying to its south. In the north, however, great continental areas lie on the cold side of both the Mediterranean and our own Pacific slopes. As a result, the southern hemisphere areas have higher and more uniform minimum temperatures in winter. This is an unfortunate fact for us gardeners on the Pacific Coast, because it places beyond reach of all but the few who have extremely favored microclimates, a large part of the wonderful shrub flora of West Australia.

There are even remarkable differences between the western Mediterranean and our Pacific Coast in this respect. The east-west mountain chains of Europe do a better job of protecting Italy, Spain and northern Africa from north winds than do our north-south mountains. Periodic great freezes, like those of 1932 and 1972, come down the Pacific Coast and devastate gardens; even the common rosemary died in many gardens with a north exposure near San Francisco in 1972. The climate of Greece and the Aegean is subject to somewhat similar cold conditions occasionally when the northeast wind from Russia, only barely warmed by its passage over the Black Sea, rushes through the gap between the mountains of Turkey and those of the Balkans.

Summer Drought

The menaces of summer are more nearly equal in all five of our Mediterranean areas, but here our own climate has perhaps the edge on all the others. When the desert climates widen to overcome large parts of their Mediterranean neighbors, Perth, Capetown, Santiago, Rome, Athens, Los Angeles and even, on rare occasions, San Francisco, can suddenly become burning ovens. At these times, plants droop, fires rage and weathermen watch in awe as their humidity meters register lows almost unheard of even in the great deserts of the world. I remember one August of almost unbearable heat throughout most of California. Day after day temperatures in the high nineties were reported from the usually cool coast and the daily maximum hovered close to 120° F. in the Central Valley. This condition occurs more frequently in the Mediterranean basin as a hot wind from the Sahara, the Sirocco, engulfs Crete, mainland Greece and sometimes Italy and Spain.

In general, however, westerly sea breezes in summer are happily the rule in all our regions. Without them, the many long days of clear skies would become unbearably hot and dry, and many of the plants that now endure this period would undoubtedly not survive. Travel brochures for Perth and Capetown stress the afternoon sea winds that afford relief on days that had begun with the threat of uncomfortable heat. The fact is that all our Mediterranean climate areas lie opposite great oceanic high pressure areas in summer and all have cold ocean currents off their shores, conditions that create cool winds but almost never bring rain. This circumstance is nowhere so marked as along the California coast, where it creates massive summer fogs that are one of the great anomalies of the world’s climate structure and which are the product of California’s peculiar topography. Our Central Valley is, in summer, a hot, low-lying area backed by high mountains and separated from the sea by lower mountains that flatten out into hills near San Francisco Bay, very nearly in the center of the valley’s western rim. Almost every summer afternoon masses of hot air rise from this basin, drawing cold air from the sea through gaps in the mountains and over the lowest of the hills. The result is the summer wind we know so well. Its regularity and strength sets in motion a cold current along the coast, colder than similar currents along the coasts of the other regions we have been considering. The air above this current often condenses into fog which is then driven inland as the cold sea air rushes into the afternoon low pressure zone of the Valley. The resulting combination of wind, fog and dry season is one that always surprises tourists to San Francisco.

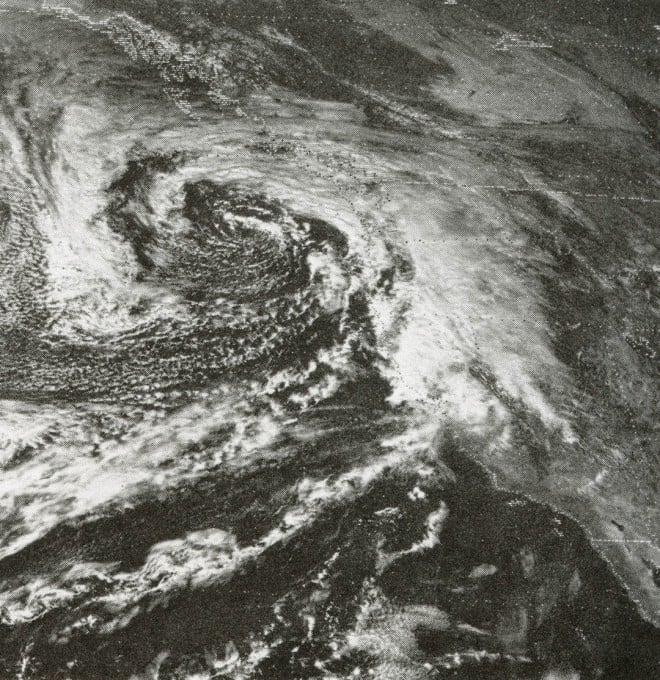

It is instructive to consider our climate from a vantage point some miles up, say at the level of a low satellite or a medium order of angels. From here, if we look toward the equator we see cloud masses as hot air rises, condenses and frequently drops its moisture. Still to the south, but closer, we see skies almost always clear as equatorial air returns to the earth, warming as it descends and therefore never condensing water vapour into rain. (The air is, of course, being driven to the east by the rotation of the earth. ) These are the deserts. In winter, if we look far to the west, across the Pacific, we can see storms gathering in a cyclonic pattern, as warm air from the south meets cold air from the north. The warm air rises and cools, condensing its moisture as rain or snow. These storms follow a great arc across the Pacific and descend along the Pacific coast. Sometimes, however, this pattern may be interrupted. Many of the storms fail to go south but instead head out across Canada toward the Great Lakes. In this case, the great Pacific high pressure area, always out to sea opposite California in summer, has failed to gravitate southward with the sun in winter. California is in for a drought.

Now, if, in another winter, we look from our place among the angels far to the east, we can see clear sky along the entire east coast. The Bermuda high has failed to gravitate south. Cold air from northeastern Canada is being forced through passes in the mountains to bring an unusual freeze to the Pacific states. On the night of December 12, 1972, when northern California was visited by what was perhaps its greatest frost of the century, minimum temperatures in Miami were 72° F. and in New York, 50° F. These, however, are the exceptions. Usually, above California, we see the descending storms in winter and clear skies in summer with westerly winds.

Such briefly are the basic facts of our Mediterranean climates more or less the best and the worst they have to offer. To those of us who are gardeners and therefore also interested in landscapes — the earth’s green mantle as it affords a home for man — these regions of winter rainfall and clear summer skies have a significance that immediately separates them in our minds from other parts of the earth. No list of facts, however long, can supplant this intuition. At the very mention of the word Mediterranean any number of landscapes come to mind: the setting of Delphi with its wooded grotto and the rich maquis out of which rise the monasteries of Athos, for example, or, in paintings, the wilderness of Calabria by Salvator Rosa; Italy as seen by Corot, or Spain, always present in the backgrounds of Velasquez. All these (and thousands more) have their counterparts in the Sonoma hills or the Mendocino coast of California or the Umpqua valley of Oregon. And these again are duplicated with some differences — in the magnificent brushland of the harbor at Albany in southwestern Australia or the tangle of plant forms of a ravine on Table Mountain. The traveler always knows when he is in a Mediterranean land.

Our purpose is to study the plants of these regions with a climate like but never quite like — our own. If we want to enlarge our repertoire of beautiful plants and if we hope to find those plants we can grow most nearly to perfection, then these are surely the places to look for them.

Responses