Kinzey Faire Revisited

Contributor

By the time I met garden creator Penny Vogel and garden owner Millie Kiggins, Kinzy Faire was already enjoying its first extended fifteen minutes of fame. In the early to mid-1990s, magazine writers swarmed the garden, which was then full of perennials, flowering shrubs, and roses surrounding the dwellings of the farmstead on the east side of a utilitarian driveway. Kinzy Faire (on Kinzy Road in Estacada, Oregon) appeared in Fine Gardening, Better Homes & Gardens, and Country Living Gardens in rapid succession.

At that time, deer had also discovered the garden. A first trip to Heronswood in 1992 yielded allegedly deer-resistant trees and large shrubs to be planted as a wide sacrificial buffer between the farmed fields and the garden proper. This part of Kinzy Faire, which Penny calls the Tree Garden, was about a year old when I first visited. At the northern end of the Tree Garden sits a chapel that Millie built and dedicated to the memory of her maternal grandparents, who had founded the original ninety-eight-acre farm. The garden’s guest book resides here, and signing it is mandatory for each visitor.

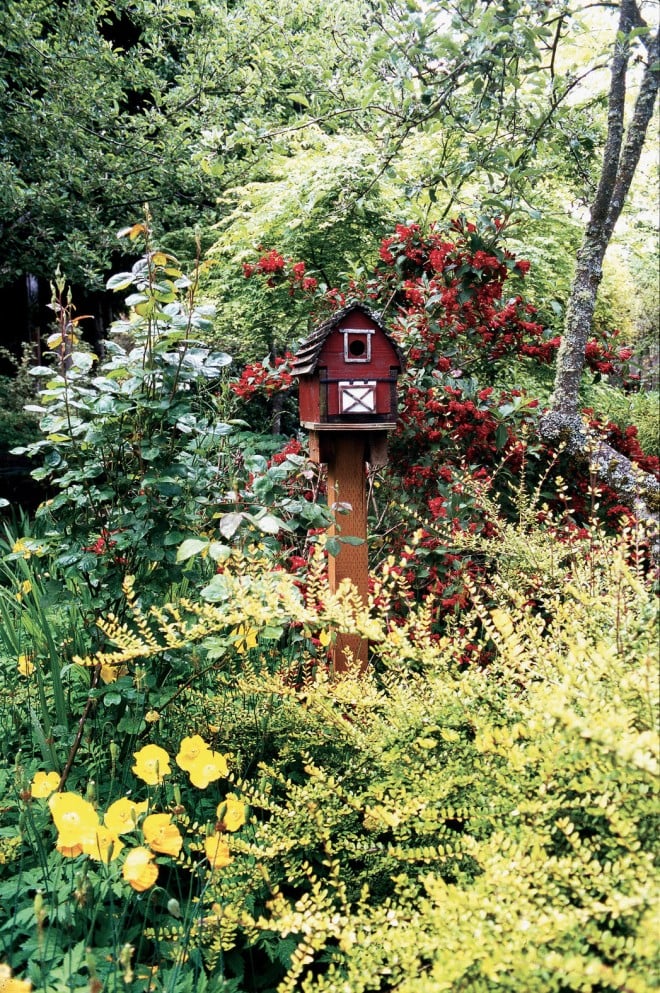

In 1991, Kinzy Faire was open for a Hardy Plant Society Study Weekend with a cottage garden theme; to say that Penny and Millie’s accomplishments dazzled visitors would be an understatement. In addition to Penny’s sumptuous plantings, they saw sheds, cottages, and bird feeders, all built by Millie. Successful gardens beget more plants than they can contain, and, for open garden events, Penny would offer plants for sale, which helped to fund her plant addiction. However, by the height of the garden’s renown, Penny had to make a choice: either maintain a nursery, or maintain the garden. Even as Millie was building a sales pavilion, Penny was deciding that gardening was much more to her liking than trying to satisfy the tastes of increasingly demanding shoppers. Penny had made up her mind: no more sales. She also decided to stop opening the garden on any regular basis. Kinzy Faire became a by-invitation-only destination, in part to sever it from its near transformation into a nursery.

“Do you want me to take down the sales house?” Millie asked.

“Oh no, leave it up, I’ll do something with it,” Penny replied. Already her “little gray cells,” as she calls them, were imagining a vine-covered shade house.

At about the same time (I remember it, clear as day), Penny stood in her driveway and told me that it was all she could do to maintain and improve the existing garden. She had no intention of letting the garden jump the driveway to invade the broad lawn around the house, approach the barn beyond, or constrict her husband Bill’s vegetable patch.

Leaping the Driveway

By 1994, when the Clackamas Community College herbaceous perennials class made its first annual pilgrimage to Kinzy Faire, the rock garden on the northwest side of Penny’s house, across the driveway from the original garden, had been planted. Penny had launched herself down a slippery slope; once the garden had a toe-hold on the far side of the driveway, the descent into massive garden expansion was swift and exhilarating.

Enlarging the deck on the back of Penny’s house revealed a large boulder, and further excavation uncovered more rock, probably rubble from previous building. Penny did what any intrepid gardener would do: add a gravel path and grow all of the choice selections of Dianthus, Oreganum, Armeria, and similar heat-seekers that do so poorly in a regular garden with lush soil. The original vertical anchor to the rock garden was a handsome, tall, blue Arizona cypress (Cupressus arizonica var. glabra ‘Blue Ice’), which has now spread into an impressive specimen. The oreganums have interbred to produce marvelous hybrids that, properly marketed (I keep telling Penny), could be the means of her retirement.

Beyond the lawn and vegetable garden behind Penny’s house, farm fields planted to wheat, clover, or alfalfa stretched into the middle ground, with Mt Hood in the distance. At the edge of the lawn, atop a slight incline above the fields, Penny inaugurated Orphan Alley. Under-performing, or overly vigorous, herbaceous perennials, such as daylilies and bearded iris, who either needed constant division or were simply not earning their place in the bigger garden, were exiled to this long, narrow border at the crest of the rise. Since she was not selling plants anymore, Penny had to put the extras somewhere, and Orphan Alley was not an easy site—full sun, maximum wind exposure, and no supplemental water. If seen at the right time of year, however—particularly with Millie’s red 1949 Jeepster making a rare appearance in the field beyond to give a boost to the borrowed view—Orphan Alley is undeniably captivating.

As Orphan Alley was installed out back, the front of Penny’s house underwent a transformation of its own. It had been just a broad arc of lawn, ending with a shallow bank down to the small parking area and road leading to the barn. A majestic curve of blended conifers, choice shrubs, and linking patterns of herbaceous perennials began to emerge. All of the mistakes made by a younger Penny, when developing the original garden, have been remembered and not repeated. Solutions to common problems often seen when visiting other gardens, and morals from the gardening school of hard knocks, come to fruition here.

Where the big border is at its widest, flowering cherries, maples, and crabapples rescued from a defunct nursery provide the canopy for a shady walk that rambles away from the remaining lawn and sunny edge. The trees cool the afternoons for swaths of Hosta, Epimedium, Heuchera, Tricyrtis, and a bevy of Helleborus. The path rejoins the lawn at the border’s farthest point from the house, under a clematis-laden arch. If you look through this arch, from the lawn, you see the tool shed built by Millie to serve as a more attractive focal point than the old barn; the shed has been hung with ancient hand tools and small farm detritus, now rendered pleasing and useful by a patina of rust. Like any good farm gal, Millie never throws anything away, and the sharp-eyed Penny sees the aesthetic possibilities in every scrap. All good things come to an end, including the superb border. But, what an ending! Inspired by a much-photographed walk of Betula utilis var. jacquemontii in the former garden of Portland designer Margaret de has van Dorser, Penny has created a grove and highlighted the cool beauty of the brilliantly white-barked birches by under-planting them with clouds of snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis) and winter-flowering cyclamen, followed by trilliums and pools of Anemone blanda to sparkle amidst punctuating spears of variegated Iris pallida and I. foetidissima, and then oceans of blue hosta for the summer—the bigger the better.

Of course, one thing leads to another, and the birch grove really isn’t an ending. One had a prime view of Orphan Alley from within the grove, as it was originally planted. Penny decided that was too powerful a juxtaposition and planted a long island bed, with a spine of formidable shrubs, to mask the madcap colors of the orphanage beyond. Anchored by blue gray China fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata), Viburnum cultivars, such as V. plicatum ‘Kern’s Pink’ (syn. ‘Sensation’), and shrub roses, this bed has turned Orphan Alley into a secret garden, accessed only from either end. From the birch grove, the soft foliage textures and pastel palette of the screening bed no longer challenge one’s repose.

If you walk around behind this shrub border and up through Orphan Alley, you emerge at an open garden room with a central lawn and a vivid spring border of bearded iris, peonies, and foxgloves on the left. You have arrived at the back of the house, where the vegetable garden now has a boundary of fence cloth covered with clematis. Often when I visit, Bill will mutter as I pass, “She’s trying to squeeze out my corn!” But Bill is as much an enabler for Penny as Millie is, quietly bringing home such delicacies as a pair of rusty gates when he returns from a trip to the dump. Now retired from the logging industry, Bill entertains himself by collecting and selling scrap metal. As Penny puts it, “As long as he comes home with better stuff than he leaves with, it’s okay with me.”

A Bright Future

The garden of Kinzy Faire now extends to three acres, and Penny tends it herself. She has given up the delusion that she can stop its increase, but she’s become quietly brilliant at directing its growth. Long out of the glare of the public eye, except for the occasional published photograph by Allan Mandell—the only professional photographer with permission to visit at will—Kinzy Faire has developed into one of the finest gardens in the Pacific Northwest. In this first decade of the new millennium, the most brilliant portions of the garden are the most unsung. The garden is seldom opened for visitors. If you’re in the area for a tour, and you know the right people, or if you take the right horticulture class, overtures can be made.

As for the older “farmyard” part of the garden, Penny continues to edit her early miscues, adding the garden bones that should have been planted in the first place. The shade house is swathed in clematis, as are most of the garden’s original structures. There is still a secret garden with a pond, but not nearly as many roses—the lame and the halting have been removed. Outside Millie’s front door, the predominant flower color is still red. That the garden continues to enlarge is a certainty; there is now an “arboretum” of Betula utilis var. jacquemontii behind Penny’s greenhouse and Bill’s shed, accessed from the old garden and under-planted with new shrubs that enhance the birches.

The future of Kinzy Faire is certain. The farm fields are being returned to forest, and Millie has made Penny her legal heir. As the reforestation continues, Penny will steward Kinzy Faire’s transition. Beyond Penny, the garden will pass to the next generation. Fortunately Penny has a daughter who is a garden designer for Tsugawa Nursery in Ridgefield, Washington, and who will cherish her mother’s intentions. In the meantime, Penny and Millie are preparing for a visit from the International Clematis Society in September 2010.

Missing from this story of Kinzy Faire is the evolution of the clematis collection, already one of the finest in the Pacific Northwest. Look for that story in the July 2010 issue of Pacific Horticulture.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses