The Sound to Olympics Trail: A Model for Integrated Greenways

Contributor

- Topics: Nature is Good For You

Summer 2025

The content and photos for this article are from a presentation at the 2024 Washington State Trails Coalition Conference titled “What’s New on the Sound to Olympics Trail and the Puget Sound to Pacific Partnership?” as well as discussions with consultants and non-profit board members.

Presenters included:

Don Willott, panel facilitator, vice president for the Sound to Olympic Trail (STO), advisor to Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation, as well as board member of North Kitsap Trails Association (NKTA), Kitsap Audubon Society, and Peninsula Trails Coalition; Jeff Bouma, RLA, planning consultant and president of Fischer Bouma Partnership; Jennifer Dvorak, PE, project manager at Parametrix; Barbara Trafton, trails manager at Bainbridge Parks & Trails Foundation.

Authors:

Sandy Fischer, FASLA, with oversight by Don Willott; Photos: Don Willott unless otherwise noted; Map Graphics: Fischer Bouma Partnership and Parametrix

This Article was made possible through a generous grant by the Bainbridge Community Foundation.

Connection is key in Kitsap County, Washington, where ferries traverse winding waterways to link vibrant communities. Soon county residents and visitors will have a new option for overland travel, thanks to an ambitious endeavor to design infrastructure that enhances both human lives and the environment.

More than just a path, the Sound to Olympics Trail (STO) creates an “active transportation spine” bracketed by a linear park and a natural corridor known as a greenway, weaving together ecological restoration, community engagement, and sustainable mobility, according to the team’s 2024 presentation. This initiative is a testament to the power of collaboration, bringing together governmental bodies, tribes, non-profits, and citizens to forge a path that connects people to each other and to the natural world.

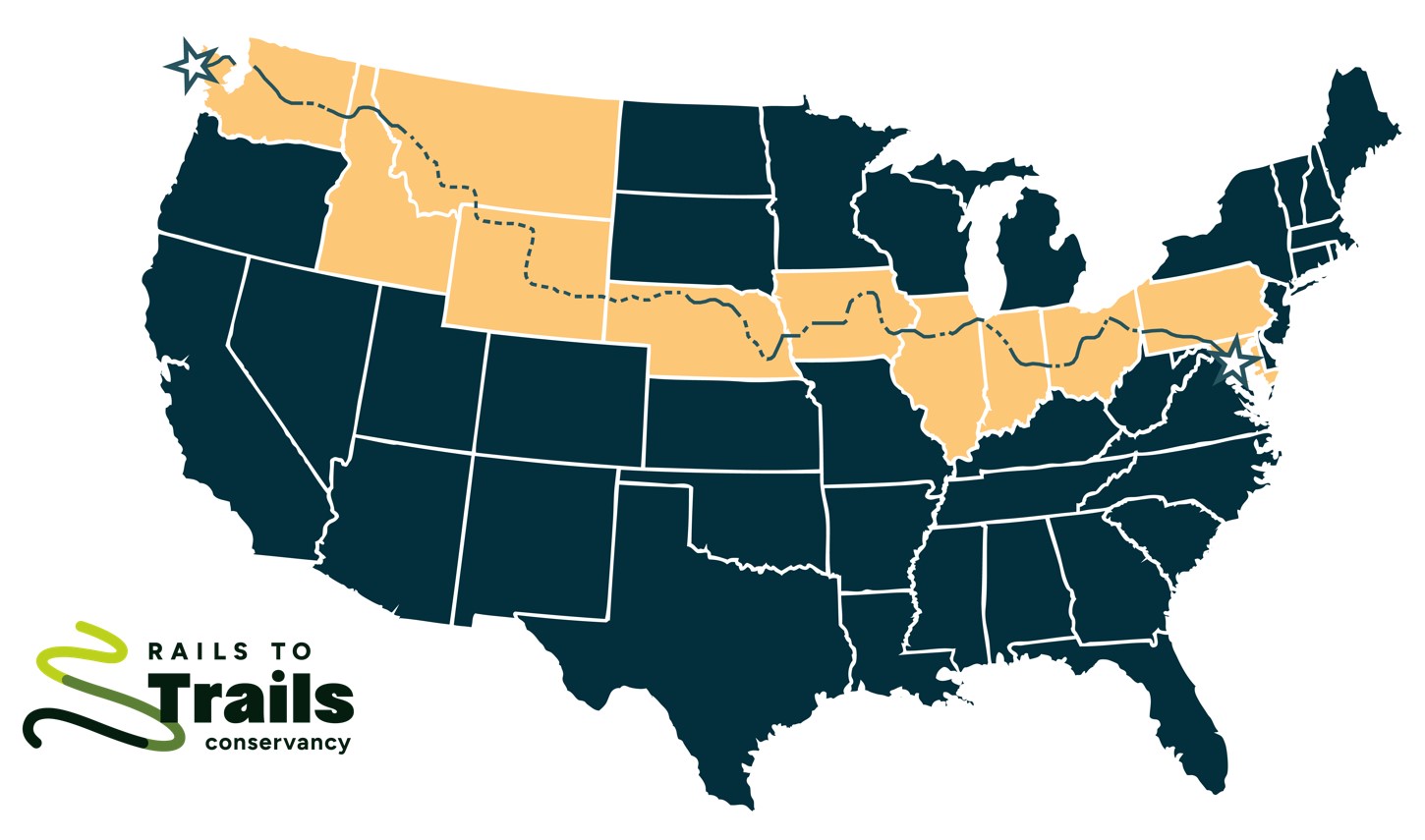

The STO is a key component of the broader Puget Sound to Pacific (PS2P) initiative, which will connect communities across a 200-mile network. PS2P itself is also a strategic link within the Great American Rail-Trail, an initiative of the Rails to Trails Conservancy. The STO and the Olympic Discovery Trail (ODT) are the westernmost segments of the Great American Rail-Trail that runs from Washington, DC, to La Push, Washington, on the Pacific Coast.

The Kitsap Forest and Bay Community Campaign coalition raised funds to purchase over 5,000 acres of former timber harvesting land for public use and conservation in Kitsap County. The Greater Peninsula Conservancy and Forterra facilitated these campaigns.

Vision and purpose

At its core, the STO project creates a corridor that serves both people and wildlife. By following universal design principles, the shared-use path is accessible to people of all ages and abilities for both recreation and transportation, while the linear park that follows the trail conserves and restores habitat.

Residents use the trail to commute to daycare, school, and work.

The greenway is used year-round.

The STO project goes beyond simple transportation. It creates a greenway for people and nature, emphasizing ecological restoration along its route. This includes augmenting native plantings, irrigating, weeding, mulching, edge-mowing, and continuously reassessing the effectiveness of these actions through a process known as adaptive management, according to the STO team. These practices restore forest health and enhance the understory, which is critical for wildlife habitat.

Ecological restoration: A cornerstone of the project

Committed to ecological restoration, the STO design team embraced the concept of linear ecology, creating continuous habitat corridors that serve wildlife while accommodating human use.

The trail serves as a testing ground for various restoration techniques, particularly in areas degraded by invasive species. STO habitat conservation strategies include selectively thinning overcrowded forest stands, creating tree snags, retaining fallen logs, managing storm water in bioswales, implementing temporary water-efficient irrigation systems, placing native plant communities based on microclimate conditions, regularly monitoring forest health indicators, and integrating climate resilience strategies.

The success of these efforts is evident in places like the Winslow Creek Ravine, where careful attention to canopy structure has allowed native species like sword fern (Polystichum spp.), inside-out flower (Vancouveria hexandra), currants (Ribes spp.), serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia), and twinberry (Lonicera involucrata) to thrive.

This careful forest restoration extends to thinning tree stands. For example, an operator threaded heavy machinery (left image above) between larger trees without damaging them or the understory. He took down the too-dense pencil trees to promote health of the forest and understory. Branches were chipped and removed, as were the sections of tree trunk. Ongoing maintenance and ecological restoration include clearing invasive plants, augmenting native plantings, weed control, mulching, pruning, and temporary irrigation.

Dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis) nest in habitat piles along Sound to Olympics Winslow Connector.

The STO project also takes an innovative approach to water management. Instead of treating water and stormwater as a problem, the design team used water as an asset. The design includes bioretention systems that enhance water quality and create habitat. These systems include bioswales and rain gardens that filter pollutants, native plants that process and remove contaminants, soil systems that trap and filter particulates, and detention areas that provide seasonal wetland habitat with varied water depths that support diverse species, along with connected water features that facilitate wildlife movement.

These water management strategies not only reduce runoff volume but also create valuable habitats that support local fauna.

Habitat creation for the rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa).

Washington State Department of Transportation bioswales and informational signage along the trail. Grass is mowed to reduce fire risk, while sedges are preserved in swales.

Wildlife integration

The Sound to Olympics Trail strengthens biodiversity by preserving and creating snags for cavity-nesting birds, maintaining fallen logs for small animal habitat and soil health, installing amphibian-friendly crossing structures, creating wildlife movement corridors with appropriate cover, developing seasonal management adjustments based on wildlife usage patterns, and monitoring population changes and adaptation patterns.

“We are creating a wildlife corridor along with a people corridor,” emphasized Don Willott, vice president for the Sound to Olympic Trail.

Community engagement and education

Visitors can learn about ecological processes and management strategies from the interpretive signs along the trail. The STO team included these signs to build public understanding of ecological restoration principles, create advocates for conservation and maintenance funding, provide opportunities for citizen science initiatives, demonstrate sustainable landscaping techniques, and engage community, including youth, in learning activities.

Signage invites visitors to learn about environmental benefits.

The STO team engages with and informs surrounding communities through planning meetings known as charettes, discussions with artists and scientists, informational presentations, groundbreaking and trail-opening celebrations, as well as educational and recreation events where neighbors meet in a linear park.

The first section of the Sound to Olympics Trail had its grand opening in March 2018, attended by attended by Bainbridge Island City Council, Congressional Representative Derek Kilmer, Mayor Kol Medina, Washington State Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz, volunteers, and residents. Read More Here

Community dinner at the Sound to Olympics community planning workshop.

Randy Purser, Suquamish Tribal Member, created welcome features for the Sound to Olympics Trail. The Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation facilitated this collaboration to celebrate local Tribal culture and partnership in a beautiful and fitting manner. The artist also created a feature on the Seattle Waterfront that serves as a ferry gateway to Kitsap County on the Seattle-to-Bainbridge ferry route.

Adaptive management and climate resilience

The STO project’s adaptive management plan includes tracking water, soil, vegetation, and wildlife. By keeping a close eye on plant establishment and health, habitat changes, drip irrigation efficiency, and invasive species, the project team will adjust its strategies based on what works best.

As climate change intensifies, these adaptive strategies become increasingly important. The project team is actively selecting plants that can adapt to changing conditions, creating connected habitat corridors that help species migrate, building community understanding of climate challenges, and developing maintenance practices that can evolve with changing conditions.

Regional connectivity and the PS2P initiative

The Sound to Olympics Trail is not an isolated project, it is a crucial component of the Puget Sound to Pacific (PS2P) initiative. The PS2P aims to connect three counties to the state trails network. It fills 100 miles of gaps in trails in Kitsap, Jefferson, and Clallam counties. This collaborative effort involves 13 jurisdictions and 34 project components.

The PS2P also links the Olympic Discovery Trail in Jefferson and Clallam counties with the Sound to Olympics Trail in Kitsap County. This connection would be a key component of the Great American Rail-Trail, a trail corridor that will span the width of the United States, covering more than 3,700 miles between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans.

The PS2P initiative recently received a $16.13 million Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grant, underscoring the project’s regional and national significance. This grant facilitates planning and design phases across multiple jurisdictions.

Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grant applicants include the City of Port Angeles with co-applicants Clallam County, Jefferson County, Kitsap County, Quileute Tribe, City of Forks, City of Sequim, City of Port Townsend, Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, Suquamish Tribe, City of Poulsbo, City of Bainbridge Island, and Washington State Department of Transportation, with support from Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation, Peninsula Trails Coalition and North Kitsap Trail Association.

Route alignments and key segments

The Sound to Olympics Trail is envisioned to be a shared-use path and greenway that is accessible to all, with a focus on universal design. Since there was no railway in Kitsap County to convert to a trail, the project leverages existing transportation corridors, such as Washington State Department of Transportation rights-of-way and major parks.

On Bainbridge Island, the trail primarily uses the state Route 305 corridor because it is wide with limited access, it has level terrain, and it provides an efficient route to the Agate Pass Bridge. The STO has two branches, one from Bainbridge Island and another from Kingston, which intersect below Port Gamble, forming a single route to the Hood Canal Bridge.

In 2018, the STO team completed the “First Mile” segment on Bainbridge Island, which consists of three projects. The Olympic Drive Project connects the ferry terminal to Winslow Way, featuring a unique bicycle left-turn lane and integration with Waypoint Park. The Winslow Connector integrates the trail with the Winslow Creek Ravine. The Sakai Pond Connector links High School Road to Sakai Park.

Sound to Olympics (STO) Winslow Connector is a welcoming gateway to STO and Bainbridge Island.

Regional master planning

Extensive regional planning has guided the development of the STO over 15 years, and has involved local and state governments, tribal leaders, non-profits, citizen volunteers, conservation, and recreation groups. The Non-Motorized Transportation Advisory Committee drafted the STO concept, enabling grant applications.

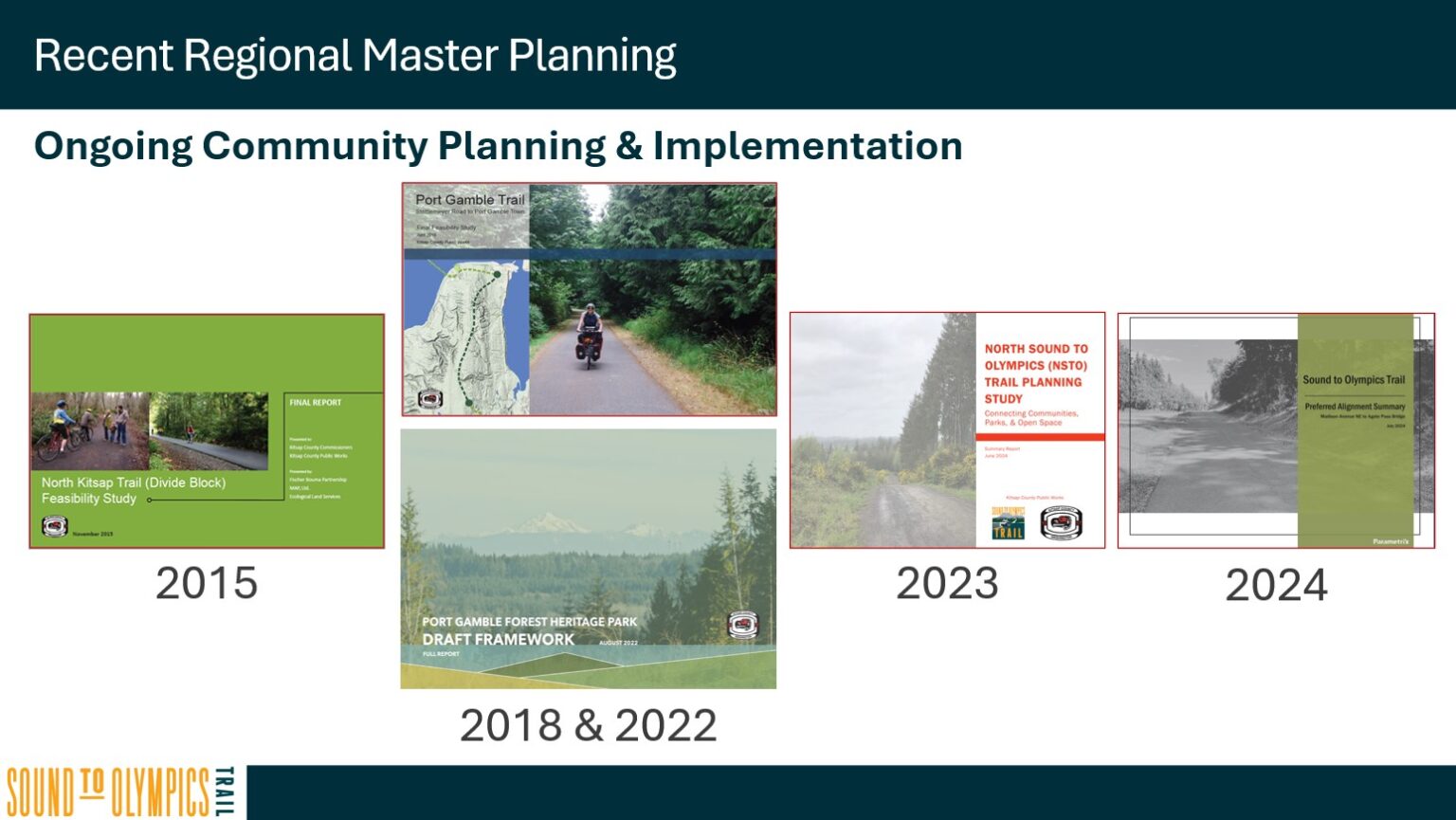

Several studies have contributed to the trail’s master planning, according to the team, including:

Divide Block Feasibility Study: Identified a 2.5-mile route and included partnerships with the Great Peninsula Conservancy and Rayonier Timber Company, protecting a sensitive wetland with a boardwalk.

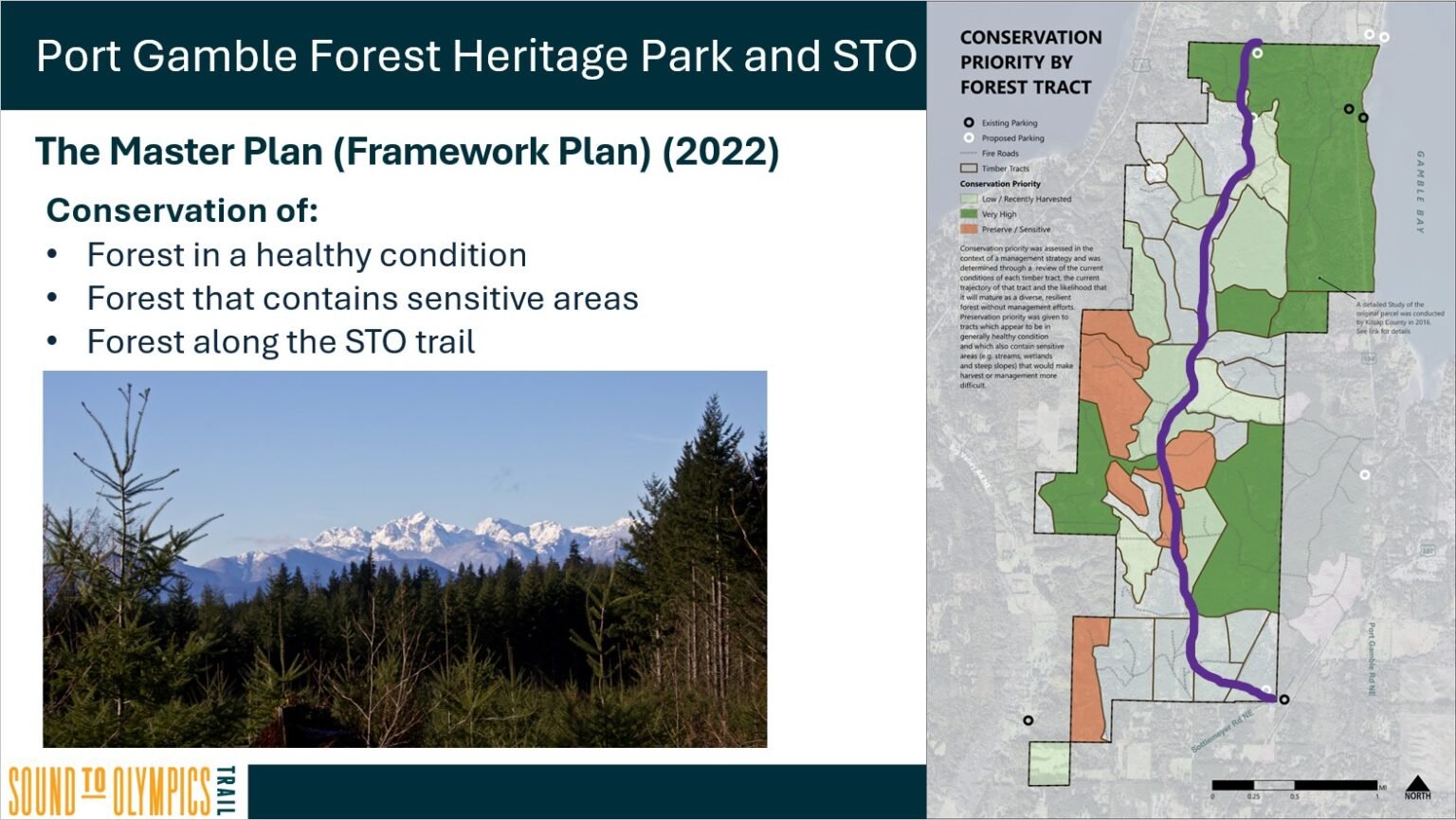

Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park & STO Trail Feasibility Study: Set aside 7 percent of the land for facilities while conserving the remaining 93 percent of land, and reclassified 50 miles of existing trails and logging roads in 2018.

North Sound to Olympics Planning Study: Will identify the best routes to connect Kingston to the south end of the Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park.

Bainbridge Sound to Olympics Design Concept: Developed two route options along the state Route 305 corridor and provided design considerations for future development.

SR305 / Johnson Parkway (Noll Road): Completed a roundabout project in Poulsbo that includes a shared-use path with an underpass, fish-passage improvements, and public art with Tribal representation.

New trails into old forests

Founded in 2014 and still gaining ground in 2025, Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park came from a collaborative effort that raised $17 million to purchase the 3,500 acres of former timber-harvesting land.

Planning priorities in Port Gamble Heritage Park included minimizing disturbance by using former logging roads, protecting trees along the corridor, and restraining recreational development to 7 percent of land. Fifty miles of existing trails and logging roads were reclassified to accommodate people recreating, such as walkers, cyclists, and equestrians. Development activities are focused on nature-based recreation and environmental education. The conservation value of all areas was inventoried, and the plan seeks to avoid impacts to ecologically and culturally sensitive areas and enhance areas with low ratings.

Challenges and solutions

Despite its grand vision, the STO project faces significant challenges.

Securing sufficient funds to complete the trail is a perennial concern. Estimates for completion range widely. Time is also a critical factor, with delays affecting both progress and costs. Delays have ranged from legal challenges, funding limitations, and permit acquisition to the pandemic. Coordinating stakeholders over a span of 150 miles requires significant effort.

In addition, the project needs to balance human use with habitat protection, manage vegetation establishment efforts and costs, address climate change through species selection and irrigation flexibility, coordinate multiple jurisdictions and stakeholders, and maintain ecological integrity while ensuring accessibility.

To overcome these challenges, the STO project emphasizes creative public-private partnerships, a unifying named project, shared momentum, effective communication channels, continuous advocacy for funding, and collaboration among everyone involved.

Lessons for practice

The Sound to Olympics Trail project offers crucial lessons for professionals in horticulture, landscape architecture, and ecological design:

Think beyond boundaries: Consider ecological connections beyond the immediate project site and plan for multiple species.

Embrace adaptive management: Monitor outcomes and adjust strategies based on observed results.

Integrate community engagement: Create educational opportunities and build stewardship programs.

Plan for long-term success: Design for maintenance efficiency, sustainable funding mechanisms, and institutional support.

Look toward the future: Plan for both current and future climate conditions.

The success of this project also highlights the value of integrating art and cultural elements to reflect local heritage, and the importance of connecting trails with existing transportation modes. The project also underscores the importance of non-profit organizations in advocating trail development and public engagement.

The role of collaboration

Collaboration is at the heart of the Sound to Olympics Trail. It exemplifies how diverse groups can unite around a shared vision to create something that benefits the entire community. The STO is a tapestry woven from the efforts of The North Kitsap Trails Association, The Peninsula Trails Coalition, The Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation, various governmental bodies, Tribal communities, volunteers, and citizens.

These diverse groups are united by a common goal to create a trail and greenway that connects communities, enhances the region’s ecology, transportation, and quality of life. This collaborative approach is not just about building a trail but about forging bonds between people and nature.

The STO project demonstrates that the future of ecological restoration may lie not just in preserving isolated habitat patches, but in creating connected networks of restored landscapes that serve both people and nature. As it continues to develop, the STO will serve as an example of how infrastructure and nature can work together rather than competing, creating a more resilient and connected future.

These connections show that trails are more than just asphalt, dirt, or gravel, but lifelines that connect people to each other, to nature, and to the places they call home.

Resources

Videos

Thinning for Forest Health on the STO Winslow Connector December 2021 | Work done with charitable donations through the Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation under supervision of Landscape architect Bart Berg.

Responses