Garden Allies: Bees II (Solitary to Social)

Contributor

Bees: From Solitary to Social

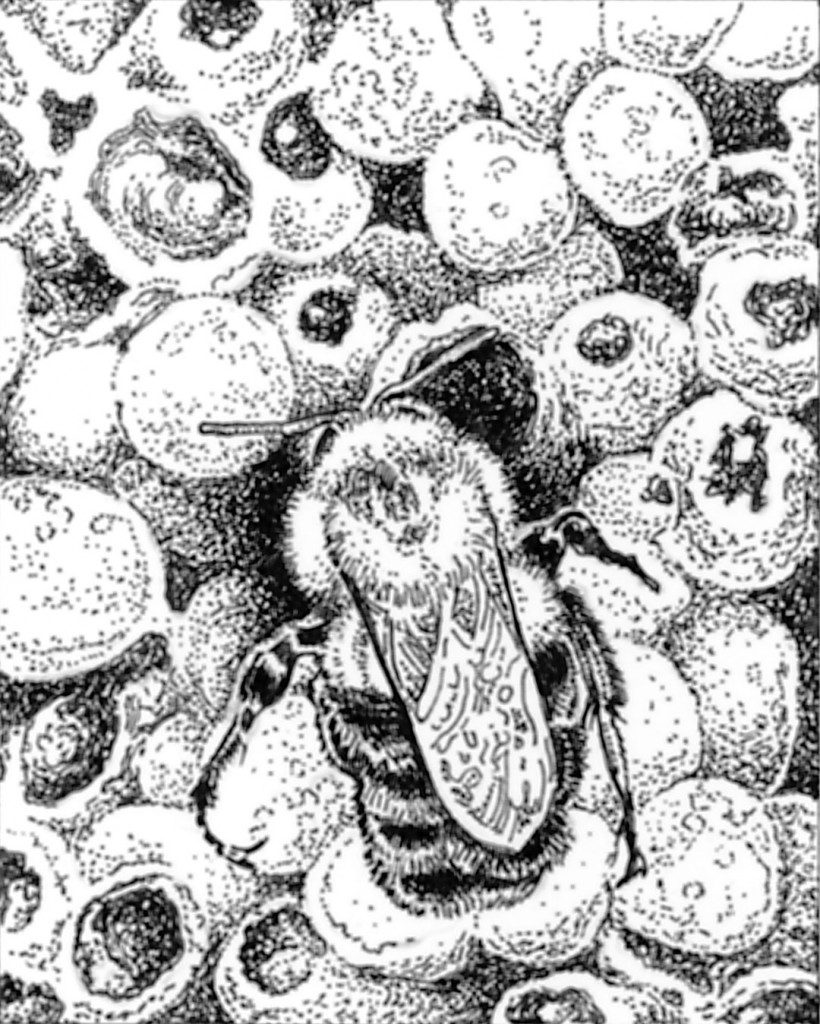

Strolling through my garden early in the morning, dew heavy on the flowers, I sometimes pause to gently pet a velvety, sleeping bumble bee. Although it may seem a strange activity, for me it embodies the ephemeral magic of the garden at dawn. I can safely pet the slumbering bumble bee because of an unusual behavior found in some members of the Apidae family of bees: males may sleep on vegetation (sometimes in aggregations), clasping stems or petals with their mandibles and spending the night at rest. Bumble bees are a common group in the Apidae, along with squash bees, long-horned bees, carpenter bees, honey bees, and several lesser known groups. Apidae have the broadest range of social behaviors of any bee family, exhibiting the full gamut from solitary to highly eusocial. They are closely followed in social diversity by the Halictidae. Families that are exclusively or principally solitary were covered a year ago click here to see Garden Allies, April 2010; honey bees are covered in April 2012.

Sociality

Eusocial bees exhibit three traits: a division of reproductive labor (only the queens reproduce), cooperation in caring for young, and an overlap of generations within colonies (daughters are workers). In advanced eusocial bees, there are also morphological differences between a queen and her workers. One group of Apidae, the corbiculate bees (named for the pollen “baskets” on the hind tibias), exhibit advanced eusocial behavior. Corbiculate bees include four tribes; bumble bees, honey bees, and orchid and stingless bees.

Between solitary and advanced eusocial bees, there are many variations on the theme of social behavior. Members of the same generation may cooperate in brood care to varying degrees. Communal bees share a common nest entrance, but each female provisions her own cells with food for her larvae. Among quasisocial bees, all females can reproduce, but cooperate in brood care. In semisocial species, there is a division of reproduction, with some laying eggs and their sisters acting as workers. In all these variants, colonies only last one year. Distinctions between these variations are difficult and sometimes intergrade.

Cleptoparasitoids, or cuckoo bees, use the strategy employed by their avian namesakes, by laying their eggs in the nest of others. Cuckoo bees steal provisions gathered by other bees, generally by laying their own egg in the other’s nest. When the cuckoo bee larva hatches, it often kills the host egg or larva, then eats the host larva’s pollen ball. Cleptoparasitoids occur in several families, most notably the entire apid subfamily Nomadinae. When social bees act as cuckoos, they are known as social parasites.

Halictidae

Some of my favorite garden bees are the bright green metallic halictid bees (Agapostemon). The female is uniformly green, while the male sports a handsome black and yellow striped abdomen. Halictids are sometimes called sweat bees, as some genera include species that appear to be attracted to perspiration. Some nest in decaying wood, but most are soil dwellers, digging their own nest. Some solitary species form aggregations, while others are known to construct nests with dozens of cells. Halictid bees include many solitary species, but also communal, semisocial, cleptoparasitoids, and social parasitoids, and the vast majority of primitively eusocial bees. The type of social interaction can vary even within the same species. Some halictids have colonies with several queens and overlapping generations (a key factor in eusociality). Colonies are usually small—less than a dozen workers.

Apidae

Apidae often brings to mind the social bumble and honey bees, but the apid family includes the gamut of social behaviors. Two important groups, the stingless bees (entirely eusocial) and the orchid bees, are only found south of the US border. Several other important groups are commonly found in gardens. Carpenter bees, both small and large, used to be in their own family but are now included with apids as modern molecular techniques are leading to revisions of taxonomic relationships. Most are solitary species, but, in some cases, mothers and daughters occupy the same nest, and some may divide the labor. Even solitary species can be found in aggregations. Large carpenter bees are familiar to most gardeners; they look like shiny black bumble bees and often behave as nectar robbers, cutting a slit at the base of a flower and taking the nectar without providing any pollination service. There are also small, solitary, metallic dark green carpenter bees, which nest in pithy stems of woody plants.

Digger and squash bees were once included in the family Anthophoridae; many are specialist pollinators. In gardens, the solitary squash bees are commonly found wherever cucurbits are grown. They arrive early in the morning before the honey bees that they resemble; some are even able to fly when it’s dark. Most are soil nesting, sometimes in aggregations. The commonly encountered long-horned bees (Melissodes species) are included in this group. Bumble bees are primitively eusocial, establishing annual colonies in old rodent burrows and other ready-made homes; only the new mated queens can over-winter. Like honey bees, they are generalist feeders, and great pollinators for the potato family (Solanaceae), dislodging the pollen by vibration (buzz pollination). They are more active in low light levels and cool weather than are honey bees. Soon after dawn, bumble bees awaken, and another day’s activity begins.

In a Nutshell

Popular Names:

Sweat bees and green metallic bees (halictids). Bumble, carpenter, digger, and squash bees (apids). Honey bees (also apids) are featured in the third installment on bees in January 2012.

Scientific Name:

Order: Hymenoptera (ants, wasps, bees), Superfamily: Apoidea (bees), Families: Halictidae and Apidae.

Common Genera:

Green metallic bees (Agapostemon), sweat bees (Halictus), long-horned bees (Melissodes), squash bees (Peponapis), and bumble bees (Bombus).

Distribution:

Worldwide, there are about 20,000 species of bees. About 3,500 species are native to North America; California is home to over 1,500 species.

Life Cycle:

Holometabolous (a complete metamorphosis from egg to larva, pupa, and adult)

Appearance:

Eggs: small, translucent, sausage-shaped; in solitary species, the egg is generally laid on a pollen ball that looks like a lump of earwax. Larvae: white, legless, grub-like, relatively inactive; eusocial bees feed and tend their larvae. Pupae: Exarate (legs and appendages are free); many species spin a cocoon around the pupa. Adults: Various, from 1/8″ to over 1″; brown, black, or sometimes metallic green or blue; may be striped yellow, white, orange, or red. Bees can be distinguished from wasps (which they sometimes resemble) by the branched hairs, especially on the thorax, that can be seen under a microscope.

Life Span:

Solitary and primitively eusocial bees live for one season; queens may live more than one season in highly eusocial bees, up to five years in some species (eg, honey bees).

Diet:

Pollen and nectar in both larval and adult stages. Some bees collect floral oils; one small group of tropical stingless bees (known as vulture bees) is specialized to feed on carrion. Diet is partly determined by tongue length: halictids are short tongued, apids are long tongued.

Favorite plants:

Nectar- and/or pollen-rich flowers for sustenance; hollow stems, leaves for nesting materials. Bees may favor blue or white flowers, but will visit flowers of any color. Many species, such as squash and blueberry bees, are oligolectic (specialists).

Benefits:

Pollination, resulting in the development of seeds and fruits.

Problems:

Large carpenter bees chew tunnels in wood, preferring punky or softwoods, such as redwood, for nesting. They can be deterred by painting the wood; alternatively, plug holes with a section of 1/2″ dowel as soon as you see them, to prevent an annual increase in aggregation size by daughters returning to nest nearby.

Interesting facts:

Bee larvae are eaten in Indonesia. If you have been buzzed by large carpenter bees, don’t worry. These are males, which cannot sting; just a harmless bluff to chase you off their territory. Some bee species are crepuscular, especially in desert habitats.

Sources:

Abundant floral resources will attract many bee species. Nesting boxes may attract bumble bees.

More information:

Garden Allies, Pacific Horticulture April 2010 [click here to see this installment of Garden Allies]

Bees, Ants and Wasps, 2010, by Grissel [click here to see review]

Attracting Native Pollinators, 2011, by Mader et al (Storey Publishing)

https://www.greatsunflower.org/

https://bugguide.net/node/view/475348. A guide to native bees of North America.

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

January Showers Bring February flowers…

Fall 2022 It may not quite have the same ring to it as the old English proverb, but it has a lot more truth to

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Responses