Watershed Moments: Moving the Needle with Rain Gardens & Water Harvesting

Contributor

Winter 2025

The good, the bad, and the ugly

New landscapes these days are so often dotted with creek beds, plopped in the middle of the yard with no rhyme or reason. These rock beds are giving rain gardens a bad name, according to Brook Sarson, engineer-turned-water-harvesting-guru of CatchingH20 in San Diego, California

“Terrible, they are lined with weed fabric and filled with rocks from point A to point B, and there’s no water harvesting going on,” Sarson said. “It’s basically one-dimensional thinking, right? It’s like, ‘Riverbeds look cool. Let’s put one in.’ But what are all the dimensions that you could factor in making it not just a feature but an asset?”

So, let’s add some dimensions.

Make it functional

Rule one, you gotta make it work.

Case in point, Brad Lefkowits of Waves Landscape Design designed his property in Encinitas, California, to be both stunning and functional. Brad’s garden features multiple rain-harvesting elements. The backyard has slimline rain tanks, with overflow feeding the natural stream elements that snake throughout the modern landscape, making the space an equally stunning feature during both dry and wet seasons.

Protecting our waterways is a huge function of rain gardens. When we cover our cities with impervious surfaces, water runs off quickly and carries all the pollutants (e.g., pesticides, fertilizers, and trash) into our waterways. When we keep that water on our properties for as long as we can, those pollutants are treated by the soil and even though trash may collect, it is better to have it and be able to pick it up than let it contaminate natural areas.

You may be familiar with the wide range of issues this causes, from eutrophication to toxic algae blooms. By retaining the “first flush”—or first inch of rain (which carries the most pollutants)—on site for the soil to bioremediate, we are keeping our waterways and oceans cleaner. We are all part of a watershed, and the same rules apply, no matter where you are.

With this type of thinking we can change so much more than just yards—we can change communities and improve neighborhoods.

In desert climates where monsoons are common, rain often comes twice a year, in summer and winter. By storing all that extra water in the ground and cisterns, one can close the gap between the rainy seasons. When a whole neighborhood gets on board, as seen in some communities in Tucson, Arizona, (see Brad Lancaster in resources below) little rain gardens create lusher, shadier spaces that buffer extremes. This creates microclimates for plants that otherwise would not grow there, including many that bear fruit.

In wetter climates and in situations where the water table is already high, the main function of a creek bed may be moving water offsite while cleaning it. Seattle, Washington-based landscape architecture firm Broadhurst + Associates removes bulkheads and creates living shorelines. The streambeds blend seamlessly with the landscape, and the new shorelines restore the landscape, creating layers of habitat for shore life.

“A Shoreline Reimagined,” designed by landscape architect Paul Broadhurst, combines native plants with a creek bed moving through the landscape and meeting up with the living shoreline on the property. Not only is this a functional and restorative landscape, but it also evokes a sense of place, while the stream bed elements blend in beautifully.

Another noteworthy function is, of course, supplied by the plants. Native plants have evolved to thrive in their native habitat with little maintenance while supporting local fauna and providing utilities such as shade, erosion control, and water storage, plus all the wellness benefits of edible plants and connection to nature are there for us humans, too. In wetter climates these plants can act as sump pumps, drinking up water as it moves through the landscape. The roots of plants also help wick water down into the ground by capillary action, while opening channels through the soil, adding organic matter as they grow old and are abandoned, decompose, and are replaced by the plant over time. These roots sequester carbon, foster healthy soils, and help the soil absorb more water. Both the plants and the soil are treating any pollutants in the process. Rock-lined swales aren’t necessary for functional spaces. Rocks will displace more water than mulch and plants, but they can also compact the soil, settling down into it. Maintenance is necessary to keep things looking good and functioning well.

Be a detective

To get started, Sarson suggests paying attention.

“One of the simplest things anyone can do is just be a detective looking around your property for moisture or water flow areas,” he said. From air conditioning condensate to gutter downspouts flooding near the foundation and taxing the storm drains, we can look at how water moves on our properties, and how we can sculpt our landscape to better move the water that comes on site.

Identify the path of least resistance. Follow the water. Whether you are on the trail or walking around your property, pay attention to where, when, and how the water moves. I find the best time to do this is during or right after a rain to notice evidence such as puddling, flooding, and movement. Going on walks around the neighborhood right after a storm is very telling, too. Areas where the streets are flooded are often adjacent to a property with zero plants and impermeable surfaces.

Just as every detective has tools for their investigation, we have our own ways to get to the bottom of our watery mysteries. Our toolkit includes earthworks that move and slow water through the landscape, such as this Imperial Beach, California, sidewalk rain garden.

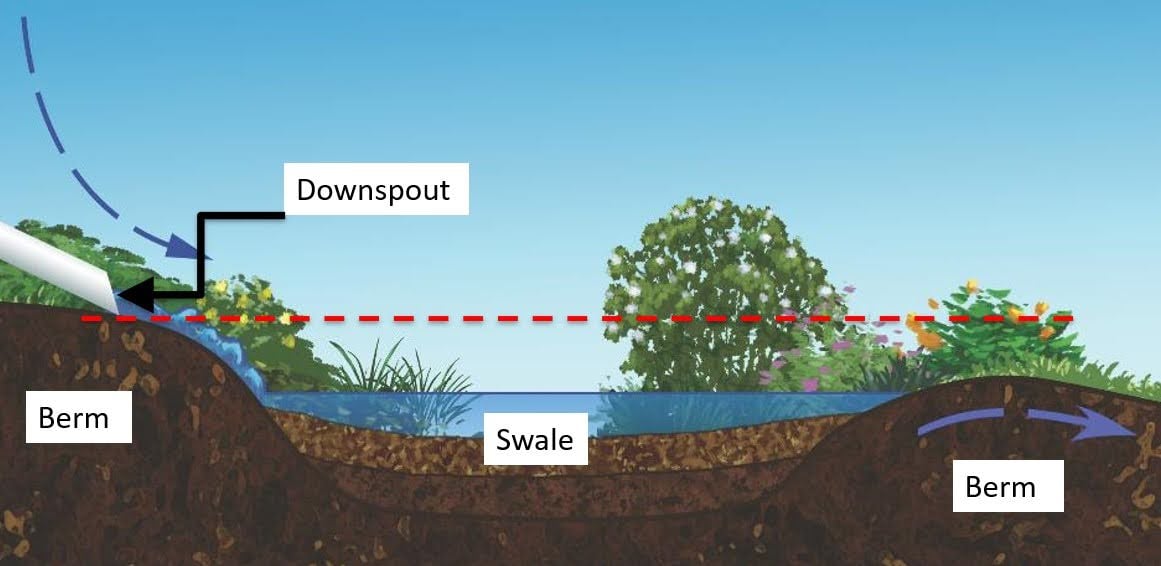

Drains can direct water through pipes that pop up in planted swales or creek beds, where surrounding mulched berms or log-berm hügelkulturs can soak up the water like a sponge. Curb cores can cut into curbs and reroute water off the street and into planted swale islands. Rain tanks come in all shapes and sizes. Cisterns and percolation basins can store and move water underground. Laundry-to-landscape and shower greywater systems are also gaining momentum (and many cities no longer require permits).

First, it all starts and ends with soil. If the soil isn’t ready to receive the water, it will not work. Mulch and organic matter are your friends. Organic material holds more moisture than the inorganic components of soil. Mulch can add organic matter to the soil and also protect the surface of the soil, keeping topsoil from blowing away and absorbing some small amount of the rainwater.

Second, be mindful of guidelines and anticipate setbacks. You want a buffer zone around structures and established trees, and you want to make sure that in the case of a heavy storm, overflow will move away from your house.

Third, always have an overflow! Stormwater can overwhelm a rain garden, it needs an escape route. On some more elaborate projects, like roof decks, overflow drains are installed above the soil level, but below the lip of planting areas and planters. For more modest projects, it may be as simple as one edge of a berm-formed rain garden being lower like in the infographic above.

When in doubt, know your limitations and when to talk to a professional. There are tools for calculating and sizing these features based on your roof size, but a knowledgeable contractor can puzzle out, run the strings, and do the math for you, which may be worth it when it’s a complicated site with drainage issues.

Make it beautiful

Finally, it should be beautiful. Anything that mimics nature should, as a mere byproduct of taking cues from the natural world, be beautiful. So, let’s look to nature and take some notes.

For example, have you ever noticed that in the wild, creeks and streams change direction when blocked by a large boulder? Where a swale or streambed starts to curve, place one or two medium boulders, and where it ends, place a larger boulder. Add plants to grow behind it, as that also happens in nature. Moisture collects on boulders and drips down, creating lush microclimates for plants. This is why weeds always grow in sidewalk cracks and why the roots of some plants travel far from the dripline to wrap around boulders. Think locally when selecting materials if you want it to evoke a sense of place.

Take a hike and pay attention to what local plants grow within, above, and below the maximum, minimum, and average water level. Does it grow in a seasonally flooded area that dries up half the year and you are in a summer-dry climate? That’s the perfect plant to include in your rain garden. Are its feet constantly wet and you are in a temperate rainforest climate? This could handle being next to or downstream from your rain swale. Are plants en masse along understories, with clusters of variety in spots along edges? How do plants arrange themselves at the edges and in clearings?

Pay attention and take notes. And when in doubt, keep it simple. You can always spice it up. Simplicity is elegant, whereas too much can easily become chaos.

Next steps

I encourage you to slow, spread, and sink your rainwater on site. If you’re going to include a stream bed, make it work for you—and the whole neighborhood! Even if you’re an apartment dweller, consider getting involved with the community and turning the sidewalk strips into tree-planted rain gardens with little pocket parks. As climate change continues to create flashier weather with more dramatic swings and intense storm systems, finding nature-based solutions to deal with our water issues just makes good sense.

Resources

For more information on what’s happening in Tucson, check out Watershed Management Group.

For resources about the Watershed Approach resources, free booklet downloads, as well as workshops and classes, check out Watershed Wise Training and Green Gardens Group.

Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond by Brad Lancaster

Responses